Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt.

Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt.

As usual, Iemon (Tatsuya Nakadai) is a disenfranchised samurai contemplating selling his sword due to his extreme poverty. Iemon had been married to a woman he loved, Oiwa (Mariko Okada), whose father called her home when Iemon lost his lord and therefore his income. Oiwa’s father is also in financial difficulty and Iemon has now discovered that he has been prostituting Oiwa’s sister, Osode (Junko Ikeuchi), and plans a similar fate for Oiwa.

Still in love with his wife, Iemon decides that his precious sword is not just for show and determines to take what he wants by force. Murdering Oiwa’s father, Iemon teams up with another reprobate, Naosuke (Kanzaburo Nakamura), who is in love with Osode and means to kill her estranged fiancee. Framing Osode’s lover Yoshimichi (Mikijiro Hira) as the killer, Iemon resumes his life with Oiwa who subsequently bears their child but as his poverty and lowly status continue Iemon remains frustrated. When a better offer arrives to marry into a wealthier family, Iemon makes a drastic decision in the name of living well.

The themes are those familiar to the classic tale as Iemon’s all consuming need to restore himself to his rightful position ruins everything positive in his life. Tatsuya Nakadai’s Iemon is among the less kind interpretations as even his original claims of romantic distress over the loss of his wife ring more of wounded pride and a desire for possession rather than a broken heart. Selling one’s sword is the final step for a samurai – it is literally selling one’s soul. Iemon’s ultimate decision not to is both an indicator of his inability to let go of his samurai past and his violent intentions as the fury of rebellion is already burning within him.

Iemon defines his quest as a desire to find “place worth living in”, but he is incapable of attuning himself to the world around him, constantly working against himself as he tries to forge a way forward. Oiwa’s desires are left largely unexplored despite the valiant efforts of Mariko Okada saddled with an underwritten part, but hers is an existence largely defined by love and duty, pulled between a husband and a father. Unaware that Iemon was responsible for her father’s death, Oiwa is happy to be reunited with him and expects that he will honour her father by enacting vengeance. Only too late does she begin to wonder what her changeable husband’s intentions really are.

An amoral man in an amoral world, Iemon’s machinations buy him nothing. Haunted by the vengeful spirit of the wife he betrayed, Iemon cannot enjoy the life he’d always wanted after purchasing it with blood, fear, and treachery. Despite the odd presence of disturbing imagery from hands in water butts to ghostly presences, Toyoda never quite achieves the level of claustrophobic inevitability on which the tale is founded. Hampered by poor production values, shooting on obvious stage sets with dull costuming and a run of the mill script, Illusion of Blood has a depressingly unambitious atmosphere content to simply retell the classic tale with the minimum of fuss. Only the final scenes offer any of Toyoda’s formal beauty as Okada appears under the cherry blossoms to offer the gloomy message that there is no true happiness and her husband’s quest has been a vain one. Achieving her vengeance even whilst Iemon affirms his intention to keep fighting right until the end, Oiwa leaves like the melancholy ghost of eternal regret but it’s all too little too late to make Illusion of Blood anything more than a middling adaptation of the classic ghost story.

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

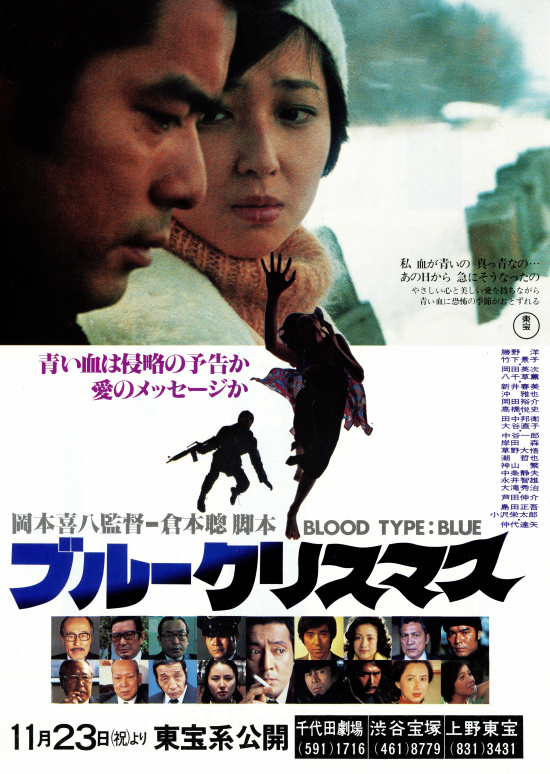

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly. The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead.

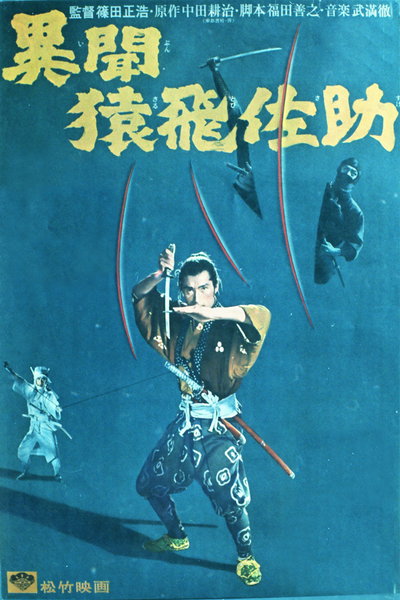

The Christmas movie has fallen out of fashion of late as genial seasonally themed romantic comedies have given way to sci-fi or fantasy blockbusters. Perhaps surprisingly seeing as Christmas in Japan is more akin to Valentine’s Day, the phenomenon has never really taken hold meaning there are a shortage of date worthy movies designed for the festive season. If you were hoping Blue Christmas (ブルークリスマス) might plug this gap with some romantic melodrama, be prepared to find your heart breaking in an entirely different way because this Kichachi Okamoto adaptation of a So Kuramoto novel is a bleak ‘70s conspiracy thriller guaranteed to kill that festive spirit stone dead. Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost? Kihachi Okamoto first made his name with his samurai movies but his output was in fact far more varied in tone than the work most often screened outside of Japan might suggest. Marked by heavy irony and close to the bone social commentary, Okamoto’s movies are nothing if not playful even in the bleakest of circumstances. He first teamed up with Japan’s indie power the Art Theatre Guild for

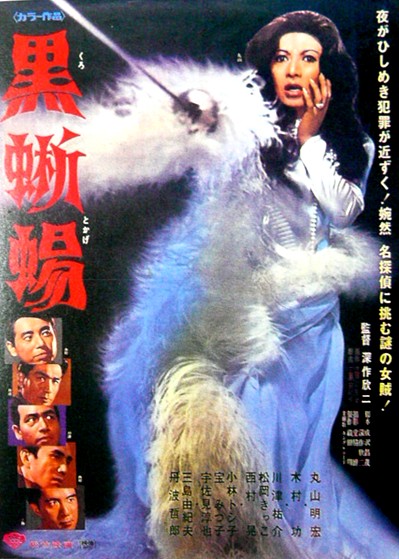

Kihachi Okamoto first made his name with his samurai movies but his output was in fact far more varied in tone than the work most often screened outside of Japan might suggest. Marked by heavy irony and close to the bone social commentary, Okamoto’s movies are nothing if not playful even in the bleakest of circumstances. He first teamed up with Japan’s indie power the Art Theatre Guild for  Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director.

Those who only know Kinji Fukasaku for his gangster epics are in for quite a shock when they sit down to watch Black Rose Mansion (黒薔薇の館, Kuro Bara no Yakata). A European inflected, camp noir gothic melodrama, Black Rose Mansion couldn’t be further from the director’s later worlds of lowlife crime and post-war inequality. This time the basis for the story is provided by Yukio Mishima, a conflicted Japanese novelist, artist and activist who may now be remembered more for the way he died than the work he created, which goes someway to explaining the film’s Art Nouveau decadence. Strange, camp and oddly fascinating Black Rose Mansion proves an enjoyably unpredictable effort from its versatile director. The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.

The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes. Bunraku playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon had a bit of a thing about double suicides which feature in a number of his plays. Though these legends of lovers driven into the arms of death by a cruel and unforgiving society are common across the world, they seem to have taken a particularly romantic route in Japanese drama. Brought to the screen by the great (if sometimes conflicted) champion of women’s cinema Kenji Mizoguchi, The Crucified Lovers (近松物語, Chikamatsu Monogatari) takes its queue from one such bunraku play and tells the sorry tale of Osan and Mohei who find themselves thrown together by a set of huge misunderstandings and subsequently falling headlong into a forbidden romance.

Bunraku playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon had a bit of a thing about double suicides which feature in a number of his plays. Though these legends of lovers driven into the arms of death by a cruel and unforgiving society are common across the world, they seem to have taken a particularly romantic route in Japanese drama. Brought to the screen by the great (if sometimes conflicted) champion of women’s cinema Kenji Mizoguchi, The Crucified Lovers (近松物語, Chikamatsu Monogatari) takes its queue from one such bunraku play and tells the sorry tale of Osan and Mohei who find themselves thrown together by a set of huge misunderstandings and subsequently falling headlong into a forbidden romance.