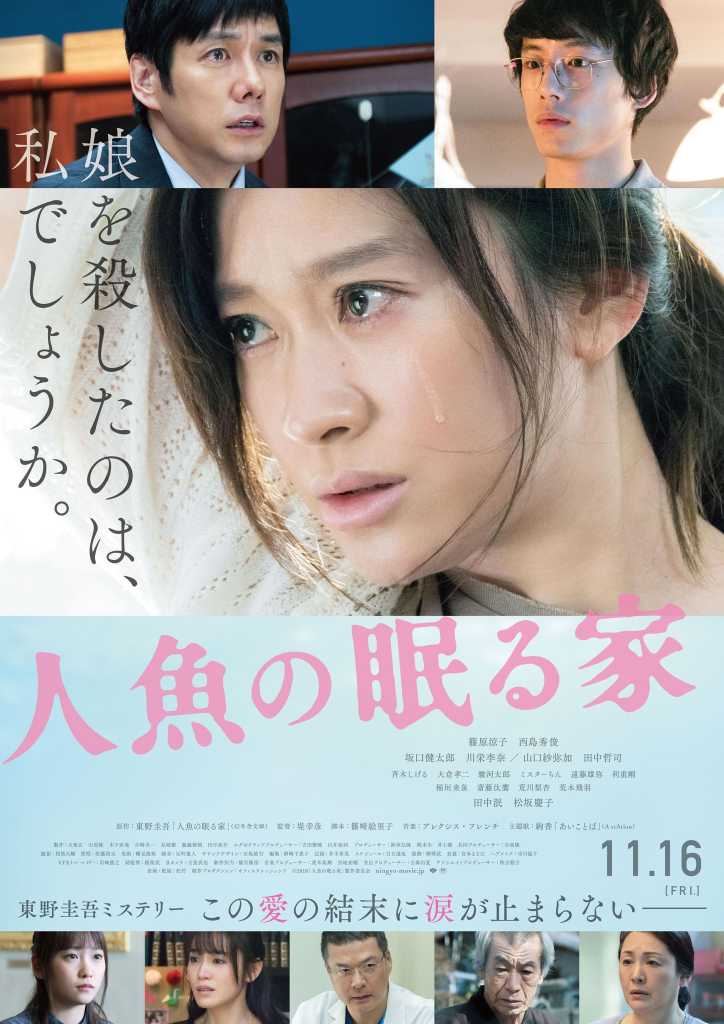

In most countries, the legal and medical definitions of death centre on activity in the brain. In Japan, however, death is only said to have occurred once the heart stops beating. The bereaved parents at the centre of The House Where the Mermaid Sleeps (人魚の眠る家, Ningyo no Nemuru Ie), adapted from the novel by Keigo Higashino, are presented with the most terrible of choices. They must accept that their daughter, Mizuho, will not recover, but are asked to decide whether she is declared brain dead now so that her organs can be used for transplantation, or wait for her heart to stop beating in a few months’ time at most. As their daughter was only six years old, they’d never discussed anything like this with her but come to the conclusion that she’d want to help other children if she could. Only when they come to say goodbye, Mizuho grasps her mother’s hand giving her possibly false hope that the doctor’s assurances that she is brain dead and will never wake up are mistaken.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that the Harimas were in the middle of a messy divorce when they got the news that Mizuho had been involved in an accident at a swimming pool. Kazumasa (Hidetoshi Nishijima), Mizuho’s father, is the CEO of a tech firm specialising in cutting edge medical technology mostly geared towards making the lives of people with disabilities easier. He does therefore have a special interest in his daughter’s condition and is willing to explore scientific solutions where most might simply accept the doctor’s first opinion. His wife, Kaoruko, meanwhile has a deep-seated faith that her daughter is still present if asleep and will one day wake up.

It so happens that one of Kazuma’s researchers (Kentaro Sakaguchi) specialises in a new kind of technology which hopes to restore motor function through artificial nerve signals controlled by computers and electromagnetic pulses. He hatches on the idea of using the technology to improve his daughter’s quality of life by letting her “exercise” to maintain muscle strength, but despite the excellent results it achieves in terms of her health, it takes them to a dark place. Muscle training might be one thing, but having Mizuho make meaningful gestures is another. They don’t mean to, but they’re manipulating her body as if she were a puppet, even forcing her to smile without her consent.

Kazumasa starts to wonder if he’s gone too far. Seeing his daughter’s face move with no emotion behind it only proves to him that she is no longer alive. Meanwhile, he comes across another parent raising money to send his daughter to America for a life saving heart transplant and begins to feel guilty that perhaps his decision was selfish. The father of the other girl sympathises with him and confides that they can’t bring themselves to pray for a donor because they know it’s the same as praying for another child’s death, but Kazumasa can’t help feeling he’s partly responsible because he made the choice to artificially prolong his daughter’s life but now realises that she is little more than a living a doll.

This is something brought home to him by Kaoruko’s increasing desire to show their daughter off. Her decision to take her to their son Ikuo’s elementary school entrance ceremony instantly causes trouble with the other parents who feign politeness but are obviously uncomfortable while the children waste no time in ostracising Ikuo because of his “creepy” sister. Kazumasa privately wonders if Kaoruko’s devotion has turned dark, if she’s somehow begun to enjoy this new closeness with her daughter to the exclusion of all else and has lost the power of rational thought. He can’t know however that perhaps she’s coming to the same conclusion as him, but it finding it much harder to accept that they might have made a mistake and all their interventions are only causing Mizuho additional suffering.

What’s best for Mizuho, however, is something that sometimes gets forgotten in the ongoing debate about the moral choices of her parents and relatives. Kazumasa’s colleagues accuse of him of misappropriation in monopolising a key researcher, hinting again at the “selfishness” of his decision to expend so much energy on treating someone whom many believe to be without hope when there are many more in need. The researcher in turn accuses Kazumasa of “jealousy” believing that he has displaced him as an “artificial” father working closely with Kaoruko in caring for their daughter. The “life” in the balance is not so much Mizuho’s but that of the traditional family which is perhaps in a sense reborn in rediscovering the blinding love that they shared for each other which will of course never fade. What they learn is to love unselfishly, that love is sometimes letting go, but also that even in endings there is a kind of continuity in the shared gift of life and the goodness left behind even after the most unbearable of losses.

Screened as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2020.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion.

The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion. Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars.

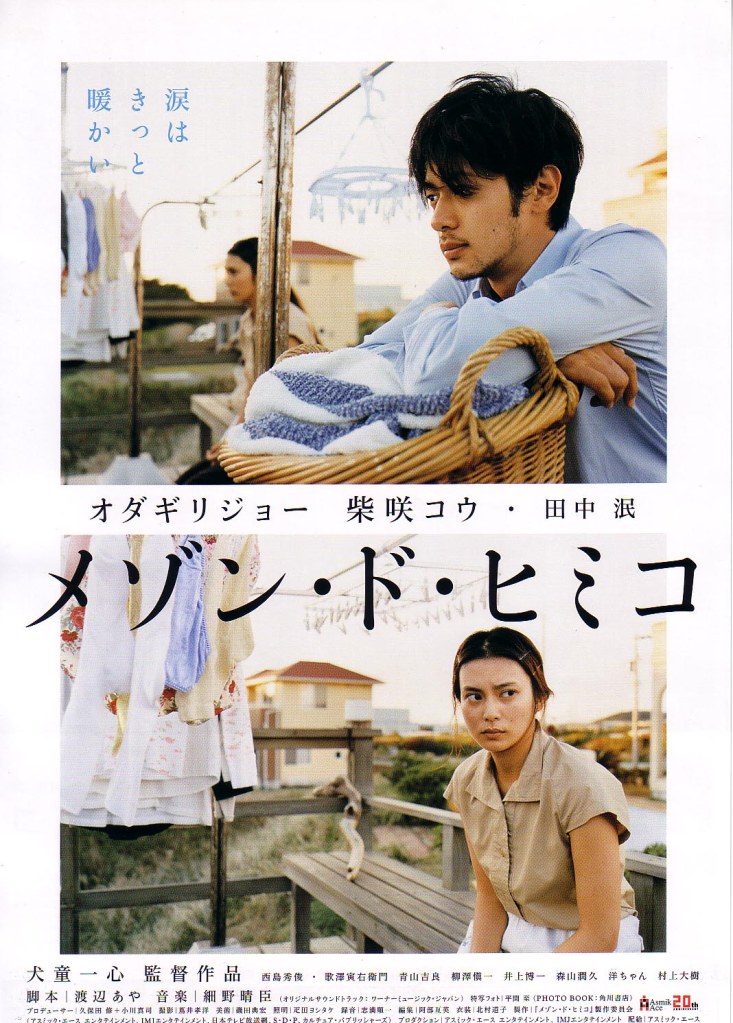

Some situations are destined to end in tears. Kaze Shindo’s Love Juice adopts the popular theme of unrequited love but complicates it with the peculiar circumstances of Tokyo at the turn of the century which requires two young women to be not just housemates but bedmates and workmates too. One is straight, one is gay and in love with her friend who seems to get off on manipulating her emotions and is overly dependent on her more responsible approach to life, but both are trapped in a low rent world of grungy nightclubs and sleazy hostess bars. In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support.

In Japan’s rapidly ageing society, there are many older people who find themselves left alone without the safety net traditionally provided by the extended family. This problem is compounded for those who’ve lived their lives outside of the mainstream which is so deeply rooted in the “traditional” familial system. La Maison de Himiko (メゾン・ド・ヒミコ) is the name of an old people’s home with a difference – it caters exclusively to older gay men who have often become estranged from their families because of their sexuality. The proprietoress, Himiko (Min Tanaka), formerly ran an upscale gay bar in Ginza before retiring to open the home but the future of the Maison is threatened now that Himiko has contracted a terminal illness and their long term patron seems set to withdraw his support. How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

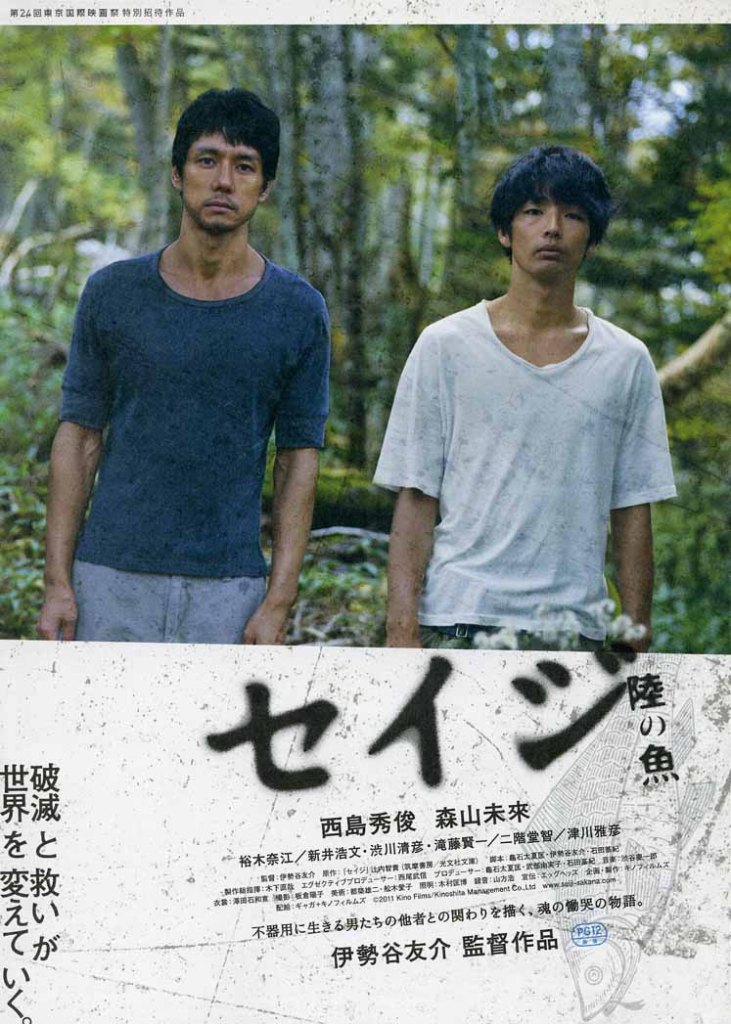

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to… Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul.

Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul. Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009.

Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009.

Outside of Japan where he is still primarily thought of as a TV comedian and celebrity figure, Takeshi Kitano is most closely associated with his often melancholy yet insistently violent existential gangster tales. His filmography, however, is one of the most diverse of all the Japanese “auteurs” and encompasses not only the aforementioned theatre of violence but also pure comedy and even coming of age drama. Dolls is not quite the anomaly that it might at first seem but perhaps few would have expected Kitano to direct such a beautifully colourful film inspired by one of Japan’s most traditional, if most obscure, art forms – bunraku puppet theatre.

Outside of Japan where he is still primarily thought of as a TV comedian and celebrity figure, Takeshi Kitano is most closely associated with his often melancholy yet insistently violent existential gangster tales. His filmography, however, is one of the most diverse of all the Japanese “auteurs” and encompasses not only the aforementioned theatre of violence but also pure comedy and even coming of age drama. Dolls is not quite the anomaly that it might at first seem but perhaps few would have expected Kitano to direct such a beautifully colourful film inspired by one of Japan’s most traditional, if most obscure, art forms – bunraku puppet theatre.