Topping the “best of 2013” lists in both Kinema Junpo and Eiga Geijitsu (something of a feat in itself), Pecoross’ Mother and Her Days (ペコロスの母に会いに行く, Pecoross no Haha ni Ai ni Iku) is a much more populist offering than might be supposed but nevertheless effectively pulls at the heartstrings. Addressing the themes of elder care and senile dementia in Japan’s rapidly ageing society, the film is both a tribute to a son’s love for his mother and to the personal suffering that coloured the majority of the mid-twentieth century in Japan.

Topping the “best of 2013” lists in both Kinema Junpo and Eiga Geijitsu (something of a feat in itself), Pecoross’ Mother and Her Days (ペコロスの母に会いに行く, Pecoross no Haha ni Ai ni Iku) is a much more populist offering than might be supposed but nevertheless effectively pulls at the heartstrings. Addressing the themes of elder care and senile dementia in Japan’s rapidly ageing society, the film is both a tribute to a son’s love for his mother and to the personal suffering that coloured the majority of the mid-twentieth century in Japan.

Based on a autobiographical manga by Yuichi Okano who uses Pecoross as his artistic name (it’s the name of a small onion and Yuichi thinks his head resembles one) Pecoross’ Mother and Her Days follows Yuichi in his daily life as he tries to adapt to his mother’s sharp decline. Yuichi is a multitalented artist who draws manga and also plays music at small bars around town, but neither of those pay very much so he also has a regular salaryman job that he’s always slacking off from. He’s also a widowed father with a grown-up son who is currently staying with Yuichi and his mother in the family home.

Ever since the death of Yuichi’s father a decade ago, his mother, Mitsue, has been gradually fading. First she was just forgetful but now she’s easily confused and distracted, often forgetting to put the telephone receiver back (though this does accidentally save her from an “ore ore” scam on the other end) or flush the toilet etc. When grandson Masaki finds her wandering the streets to buy alcohol for the long dead grandfather, the pair start to worry if she might be becoming a danger to herself and perhaps they really do need to consider more specialist care for her.

Of course, the decision to place an elderly parent in a home is a difficult one, especially in a culture where the elderly have traditionally been looked after by family. Generally, the daughter-in-law would end up being responsible for the often onerous task of caring for her in-laws as well as her husband, children and the household in general. Yuichi is a widower who can’t be home all day to watch to his mother and there’s always the fear that she might accidentally do harm to herself in her increasingly confused state.

Mitsue quite often becomes unstuck in time, remembering places and events from decades before as if there were happening right now. Born near Nagasaki, she remembers seeing the giant mushroom cloud rising from the atomic bomb and being worried for a young friend who’d been sent to the city only a short time before. The eldest of ten children she looks back on her childhood which had its fair share of hardships and loss. She became physically strong working in the fields and later married a weak willed man who took to drink and was often violent. Through her ruminations and fixations, Yuichi comes to discover a little more about his mother’s history deepening his respect for her and all that she endured in raising him.

The scene where Yuichi first leaves his mother at the home is heartbreaking as he slowly watches her receding in his rear view mirror, confused and hurt at having been abandoned. However, the staff at the care home are shown to be a group of dedicated and caring people who have the proper knowledge to fully cater to Mitsue’s needs. The other elderly residents each have very different symptoms from one woman who’s regressed to her childhood when she was class president at school and now thinks all the nurses are teachers, to a wheelchair bound man who keeps trying to inappropriately touch the female members of staff (though this is apparently just the way he is rather than any kind of condition). The home isn’t a sad place or a sterile one like a hospital, the guests are well stimulated, loved and cared for and Yuichi is welcome to visit and take his mother out on trips whenever he likes.

Though often sad, the events are depicted in the most humorous way possible often using the cute manga drawings Yuichi is making about his mother and there are also long stretches of animation reflecting on Mitsue’s life. The film is, however, unabashedly sentimental and proves a little too saccharine even if obviously sincere. Curiously pedestrian for such a highly praised film though anchored by superlative performances, Pecoross’ Mother and her Days perhaps plays better to a specific audience who are better placed to appreciate its historical meanderings and sweetly sentimental tone but may leave others feeling a little underwhelmed.

Reviewed as part of the Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme 2016.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with. It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own.

It used to be that movies about marital discord typically ended in a tearful reconciliation and the promise of greater love and understanding between two people who’ve taken a vow to spend their lives together. These endings reinforce the importance of the traditional family which is, after all, what a lot of Japanese cinema is based on. However, times have changed and now there’s more room for different narratives – stories of women who’ve had enough with their useless, deadbeat man children and decide to make a go of things on their own. “Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty.

“Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty. When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.

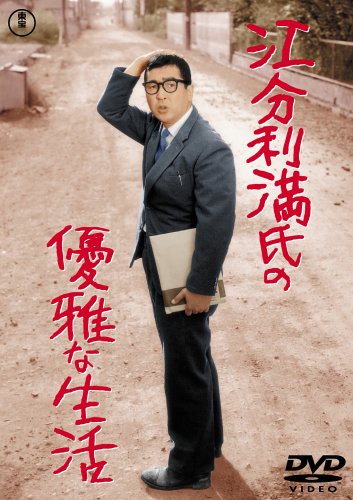

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes. Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour. Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours.

Okinawa might be a popular tourist destination but behind the beachside bars and fun loving nightlife there’s a thriving community of local people making their everyday lives here. Just like everywhere else, life can be tough when you’re young and the town’s teenagers lament that there’s just not much for them to do. A small group of high schoolers have formed a rock band but they’re quickly kicked out of their practice spot at school after a series of noise complaints from neighbours. When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age.

When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age. A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful.

A Japanese tragedy, or the tragedy of Japan? In Kinoshita’s mind, there was no greater tragedy than the war itself though perhaps what came after was little better. Made only eight years after Japan’s defeat, Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1953 film A Japanese Tragedy (日本の悲劇, Nihon no Higeki) is the story of a woman who sacrificed everything it was possible to sacrifice to keep her children safe, well fed and to invest some kind of hope in a better future for them. However, when you’ve had to go to such lengths to merely to stay alive, you may find that afterwards there’s only shame and recrimination from those who ought to be most grateful.