Japan Society New York and ACA Cinema Project will present The Female Gaze: Women Filmmakers from JAPAN CUTS and Beyond from Nov. 11 to 20, a new series focussing on the work of female filmmakers from directors to screenwriters, producers, and cinematographers.

November 11, 2022 at 7:00 PM: Wedding High

A wedding planner has her work cut out for her when a young couple’s wedding day spirals out of control thanks to competitive speechmaking, over-invested guests, an ex on their way to stage a rescue, and a thief who’s just snuck in unnoticed, in an ensemble comedy from Akiko Ohku (Tremble All You Want).

November 12, 2022 at 1:00 PM: Dreaming of the Meridian Arc

A TV drama series centring on Tadataka Ino who produced the first map of Japan in 1821 hits a snag when it’s discovered that he died three years into the project but his assistants covered it up and decided to complete the map in his honour.

November 12, 2022 at 5:00 PM: She is me, I am her

Four-part anthology film from Mayu Nakamura (Intimate Stranger) starring Nahana in a series of tales of urban loneliness and unexpected connection in pandemic-era Tokyo.

November 12, 2022 at 7:00 PM: One Summer Story

A classic summer adventure movie from Shuichi Okita in which a high school girl embarks on a journey of discovery trying to track down her estranged birth father, a former cult leader. Review.

November 13, 2022 at 1:00 PM: Good Stripes

A young couple on the verge of breaking up attempt to come to terms with an unexpected pregnancy in Yukiko Sode’s zeitgesity drama. Review.

November 13, 2022 at 4:00 PM: The Nighthawk’s First Love

Adaptation of the Rio Shimamoto novel following a young woman who has a facial birthmark that has left her afraid to pursue love but encounters new possibilities when invited to appear in a film.

November 18, 2022 at 8:00 PM: Riverside Mukolitta

Warmhearted quirky drama from Naoko Ogigami in which a man recently released from prison attempts to start again in a quiet rural town while unexpectedly forced to deal with the unclaimed remains of his estranged father. Review.

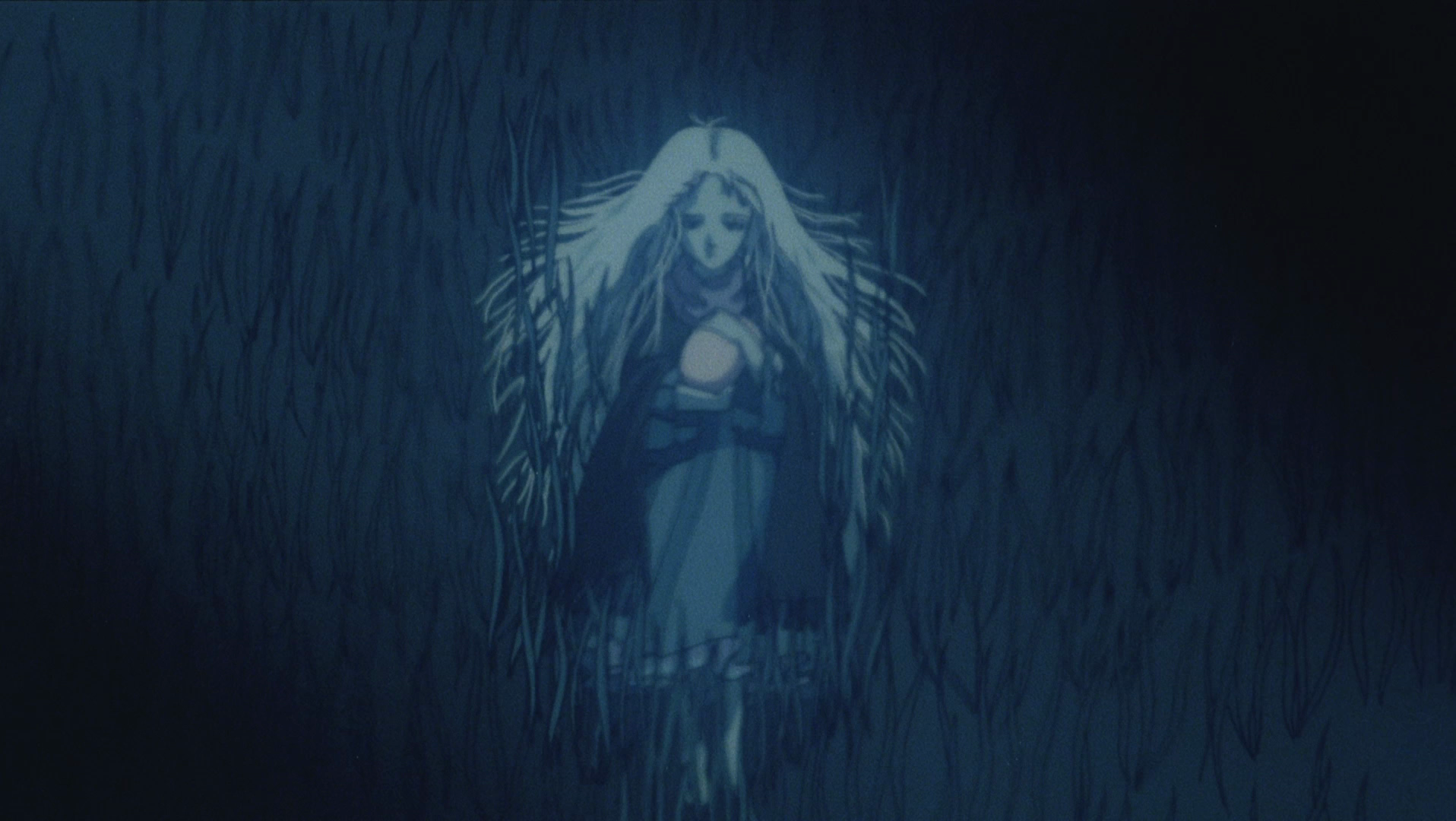

November 19, 2022 at 1:00 PM: No Longer Human

Visually striking drama inspired by the life of Osamu Dazai (Shun Oguri) as seen by the three women who surrounded him: his legal wife (Rie Miyazawa), sometime mistress (Erika Sawajiri), and the woman he died with (Fumi Nikaido). Review.

November 19, 2022 at 7:00 PM: Let Me Hear It Barefoot

Somehow in dialogue with Wong Kar-Wai’s Happy Together, Riho Kudo’s second feature follows two young men seeking escape from moribund small-town Japan and temporarily finding it in recording elaborate soundscapes for the benefit of an older woman who dreamed of travelling abroad. Review.

November 20, 2022 at 1:00 PM: Nagi’s Island

A young girl begins to heal from the trauma of her parents’ divorce and violent marriage while living with her grandmother on an idyllic island in a laidback heartwarming drama from Masahiko Nagasawa. Review.

November 20, 2022 at 4:00 PM: a stitch of life

Poignant drama from Yukiko Mishima in which a woman running a tiny boutique almost unchanged from her grandmother’s time is courted by a big fashion brand but eventually finds the courage to embrace change on her own terms. Review.

November 20, 2022 at 7:00 PM: Plan 75

Chie Hayakawa expands her 10 Years Japan short to explore a dystopian future in which the government has launched a voluntary euthanasia program for those aged over 75. Starring golden age star Chieko Baisho, the film explores the effects of the program on a Plan 75 volunteer, a salesman, and a caregiver in a society which has largely decided to discard those which it views as “unproductive”.

Classics Focus on Natto Wada and Yoko Mizuki

November 13, 2022 at 7:00: Her Brother

Kon Ichikawa drama adapted from the autobiographical novel by Aya Koda and scripted by Yoko Mizuki in which a young woman is forced to sacrifice herself for her family becoming a surrogate mother figure for her delinquent younger brother. Review.

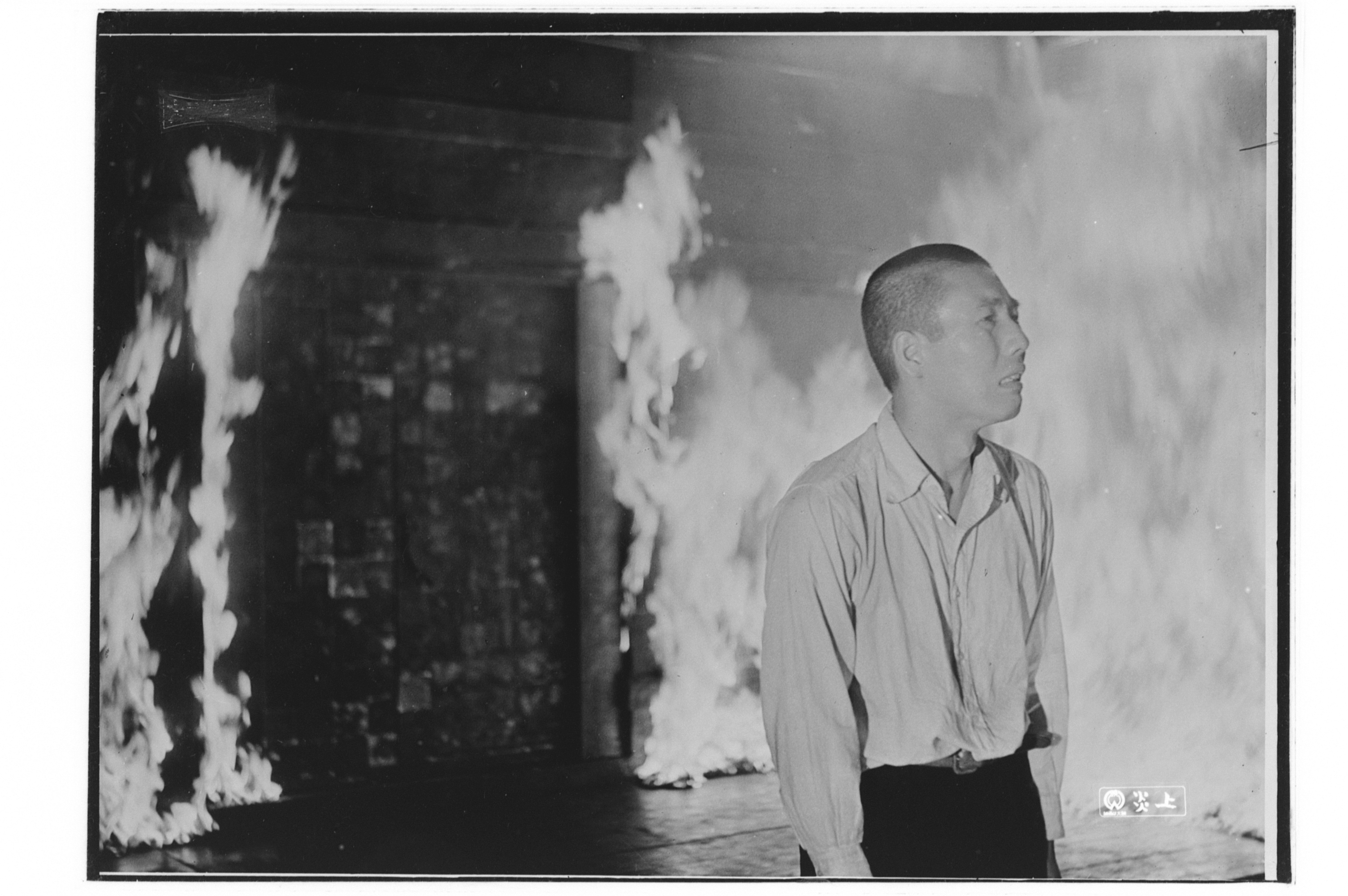

November 14, 2022 at 7:00 PM: Conflagration

Adaptation of the Mishima novel directed by Kon Ichikawa and scripted by his wife Natto Wada in which a young man is driven to the brink of despair believing that the world has become so corrupt and polluted that beauty is in its way offensive.

Filmmakers in the Rise

November 15, 2022 at 7:30 PM: Two of Us / Long-Term Coffee Break

Two shorts including Risa Negishi’s Two of Us focussing on two women in various stages of loneliness and, Naoya Fujita’s Long-Term Coffee Break following a couple through a relationship that began with a cup of coffee.

November 18, 2022 at 5:00 PM: His Lost Name

Sensitive drama from Nanako Hirose in which an old man’s decision to take in a young man he finds at the riverbank places him at odds with his family. Review.

The Female Gaze: Women Filmmakers from JAPAN CUTS and Beyond runs from Nov. 11 to 20 at Japan Society New York. Full details for all the films along with ticketing links are available via the official website and you can also keep up with all the latest details by following the festival’s official Facebook page and Twitter account.