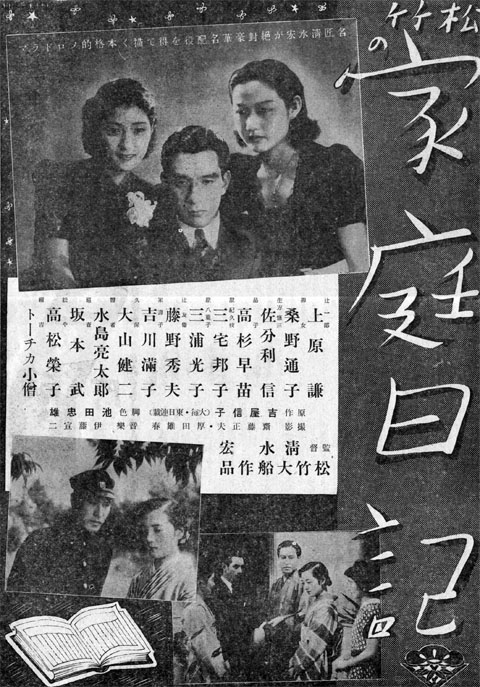

Despite the unending popularity of the romantic melodrama, Hiroshi Shimizu never quite got the bug. For Shimizu, romance is always abstracted – it either goes unresolved or reaches a point of resolution but only through unpleasant or unpalatable circumstances. There are few unambiguously “happy” couples in Shimizu’s movies, but Family Diary (家庭日記, Katei Nikki) takes things one step further in its twin tales of the romantic destinies of two very different students one of whom took the sensible path and the other the path of foolish love.

Despite the unending popularity of the romantic melodrama, Hiroshi Shimizu never quite got the bug. For Shimizu, romance is always abstracted – it either goes unresolved or reaches a point of resolution but only through unpleasant or unpalatable circumstances. There are few unambiguously “happy” couples in Shimizu’s movies, but Family Diary (家庭日記, Katei Nikki) takes things one step further in its twin tales of the romantic destinies of two very different students one of whom took the sensible path and the other the path of foolish love.

First we meet the sensible one. Fuji (Shin Saburi) takes a last twilight stroll with his current girlfriend, Kikue (Kuniko Miyake), after which they burn their letters as a symbol of their parting. Now that his brother’s business has failed, Fuji is marrying into a wealthy family who will pay for the remainder of his studies. Meanwhile his best friend, Tsuji (Ken Uehara), is grumpily drinking with a bar girl he plans to marry despite the objection of his parents. Fuji marries Shinako (Sanae Takasugi) and becomes an Ubukata while Tsuji marries Ume (Michiko Kuwano) and goes to Dalian in Manchuria. Some years later when Tsuji returns to Tokyo along with his wife and son, Ubukata has become a successful, happily married man. Coincidentally, Kikue who had gone to Manchuria to escape her heartbreak has also returned and opened up a small hairdressing shop which runs herself as a single woman looking after her younger sister, Yaeko (Mitsuko Miura).

The contrast between Ubukata and Tsuji is set up early on as Ubukata is repeatedly categorised as cold and unfeeling where as Tsuji is unmanly and oversensitive. Ubukata describes Tsuji as “sentimental”, “too delicate”, “almost the artistic type” for his compassionate desire to avoid awkwardness between their wives who, after all, must at least try to become friends if the relationship between the men is to be maintained. He urges him to “think about simpler things” which is most often the way Ubukata appears to think. That is not to say it didn’t hurt to abandon Kikue, but he comforted himself in the knowledge that he was doing the “best” thing based on a series of practical calculations. Ubukata is not heartless, but he is a committed pragmatist and sometimes insensitive to the suffering of others who might not agree with the way he works things out as his wife suggests when she (cheerfully enough) reproaches him for not paying attention to other people’s feelings.

Tsuji, having chosen to marry for love, at times seems envious of Ubukata’s settled home life with his traditional Japanese wife who trails behind him in kimono and rarely goes out without informing her husband first. Where Ubukata’s match might be seen as a betrayal of love for money, his home is harmonious whereas the Tsujis’ is not. Ubukata, it has to be said, is polite enough to Ume but makes no secret of his distaste for her unrefined character. Tsuji’s parents objected to the match because Ume was a bar girl (and, it is implied, a casual prostitute) and though Tsuji has no problem with her past, the snobbish attitudes of men like Ubukata continue to plague her however much she tries to play by the rules of their society. When Ubukata takes Tsuji to dinner, Tsuji asks him not to tell Shinako about Ume’s past in case she looks down on her to which Ubukata tells him he’s being over sensitive but later consents if only because he finds the subject distasteful in any case and is an old fashioned gallant sort of man.

Ume is however out of place in this upper middle-class environment as she demonstrates by provocatively lighting a cigarette while entertaining Ubukata and Shinako who ends up lighting it for her with a look of mild awe in her eyes. Ume fears this world will reject her – something it ultimately does when Tsuji tries to reconnect with his family, but in reality she has already rejected it herself. Unable to see past her own fears and regrets she doubts her husband’s love and lives in constant anxiety, waiting for the next slight from a hoity toity housewife to remind her that she doesn’t deserve all of this “happiness”. Though the Tsujis are “unhappy” there is also love, even if it is complicated and often misunderstood.

Both marriages are ultimately destabilised by external forces – Tsuji’s by his family’s attempts to expunge Ume by “stealing” her son and later plotting to pay her off on the condition she absent herself, and Ubukata’s by the resurfacing of the romantic love that he sacrificed for material gain. Though Ubukata has no intention of rehashing the past, he does want to be of service to Kikue (again, misreading her feelings and attempting to make himself feel better rather than improve the fortunes of another) – something which places a wedge between himself and his wife when she eventually learns of the circumstances which led to her marriage. Yet the wedge itself is not so much caused by Kikue as by Ubukata’s supreme coolness in which he sees no reason to explain himself to his wife because his actions have satisfied his own sense of righteousness and must therefore also satisfy hers.

Though Shinako is tempted by the sophisticated, westernised ways of “modern girl” Ume, and later pressed by fears her husband has never loved her, she remains a steadfast Japanese wife, effortlessly poised and always polite even under emotional duress. Despite their obvious differences, Shinako comes to care for Ume – even becoming something like her only friend, but Ume is only “accepted” by the world of the film after she “proves” herself as an emotional woman through an act of self inflicted violence which somehow demonstrates her essential purity and goodheartedness. Ume prepares to make an exit before being shown the door, but her act of pure desperation and extreme wretchedness becomes her social salvation and finally earns her a place in the moral universe of practical men like Ubukata who now rate her worthy. Thus the social order is restored, the official bonds of marriage held up, and Ubukata’s callous and calculating way of life found to be the better course, but there’s something less than convincing in Shinako’s assertion that everything will be alright now as she and her husband become another of Shimizu’s figures disappearing over a distant bridge.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old.

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old. Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence.

Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence. Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way.

Shimizu, strenuously avoiding comment on the current situation, retreats entirely from urban society for this 1941 effort, Introspection Tower (みかへりの塔, Mikaheri no Tou). Set entirely within the confines of a progressive reformatory for troubled children, the film does, however, praise the virtues popular at the time from self discipline to community mindedness and the ability to put the individual to one side in order for the group to prosper. These qualities are, of course, common to both the extreme left and extreme right and Shimizu is walking a tightrope here, strung up over a great chasm of political thought, but as usual he does so with a broad smile whilst sticking to his humanist values all the way. It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth.

It’s tough being young. The Boss’ Son At College (大学の若旦那, Daigaku no Wakadanna) is the first, and only surviving, film in a series which followed the adventures of the well to do son of a soy sauce manufacturer set in the contemporary era. Somewhat autobiographical, Shimizu’s film centres around the titular boss’ son as he struggles with conflicting influences – those of his father and the traditional past and those of his forward looking, hedonistic youth. Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind. Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all.

Sad stories of single mothers forced to work in the world of low entertainment are not exactly rare in pre-war Japanese cinema yet Hiroshi Shimizu’s 1937 entry, Forget Love For Now (Koi mo Wasurete) , puts his on own characteristic spin on things by looking at the situation through the eyes of the young son, Haru (Jun Yokoyama). Frustrated by both social and economic woes, little Haru’s life is blighted by loneliness and resentment culminating in tragedy for all. Following on from

Following on from