According to the narrator of Sadao Nakajima’s artistically daring Memoir of Japanese Assassins (日本暗殺秘録, Nihon ansatsu hiroku) the practice of assassination had got so out of hand in the early years of Meiji that the emperor was forced to institute a law banning it while accepting responsibility for the lawlessness his imperfect governance had produced. But by opening with the Sakurada Gate Indecent from 1860, the film seems to be asking what went wrong in Meiji and why the assassinations have still not stopped with the implication that more may be on their way in rather febrile political atmosphere of the late 1960s in the run up to the renewal of the Anpo security treaty with Asama Sanso still a few years away.

The answer to the question that it presents, is that oppression has still not ended in Japan and that most of these assassinations took place because people had enough of difficult social conditions those in power little did to address. However, the first few pre-20th century assassinations which are presented in the form of short vignettes, are largely a product of the confusion of the bakumatsu era as reactionaries attempt to halt Japan’s increasing openness to the wider world and what they see as a loss of national identity and sovereignty. The implication is that this sense of ideological conflict is a direct cause of the nationalism that defined the first half of the 20th century.

It’s not until we reach the early 1920s that the secondary cause of Japan’s dire economic situation rears its head as the right-wing nationalist leader of Righteousness Corps of the Divine Land (Bunta Sugawara), a society dedicated to workers’ rights, assassinates the head of a family-run conglomerate he accuses of feeding on the blood on the common man. From this incident we can see that it is not as easy to draw a line between left and right in terms of political ideology as it might be at other times or in other nations as otherwise nationalist forces share ideas that might lean more towards socialist ideals. Ikki Kita whose philosophy informed the February 26th Incident that ends the film described himself as socialist, but is also regarded by some as the architect of Japanese fascism. With the so-called “Showa Restoration”, he advocated for the elimination of private property and a doctrine of socialism from above in which the emperor would assist in the reorganisation of society. Which is to say, the clarification of the Meiji Restoration actually meant.

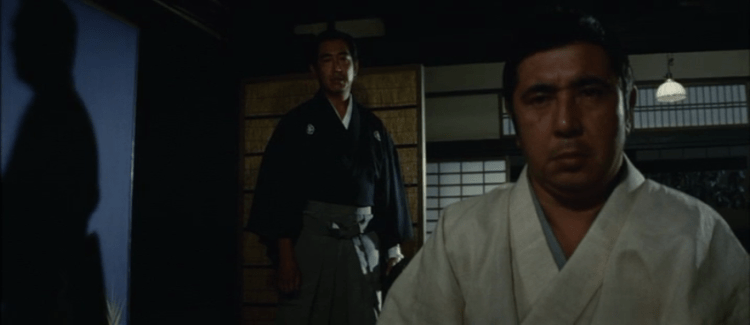

In any case, it’s easy to see the reasons that these ideas caught hold and that concepts such as “revolution” were a counter to the persistent hopelessness of the depression and the extreme poverty of Japanese society while the large conglomerates prospered through trading with the United States. The bulk of the film focuses on Onuma who assassinated Junnosuke Inoue in 1932 as part of an intended reign of terror known as the League of Blood instituted by the far right Nichizen Buddhism cult led by Nissho Inoue (Chiezo Kataoka),. Onuma was still alive at the time the film was made and apparently acted as a consultant. Played by a fresh-faced Shinichi Chiba, he’s depicted as an earnest young man who is driven into the ground by the increasingly capitalist mentality of the 1920s, a time of high unemployment and frequent labour disputes only exacerbated by the Great Depression.

Though he had been a bright and attentive student, Onuma was forced to leave education because of his father’s early death and thereafter worked a series of causal jobs before leaving a position at a kimono dyers because of their callous treatment of another employee who was forced to embezzle money because his mother was ill and he was denied a loan by the boss who justifies his position by stating that he’s already given the man several advances on his salary. Onuma’s brother also resigned from his job to take responsibility for failing to spot someone else’s embezzlement, leading Onuma to conclude that being honest gets you nowhere in this morally corrupt society. This is rammed home for him at his next job at a cake baker’s where he becomes almost part of the family and draws closer to the maid, Takako (Junko Fuji). The boss intends to rapidly expand the business by building a bigger factory hoping to capitalise on the coronation of the new emperor. Staking everything on the factory, he takes out loans from loan sharks but fails to get a business permit from the police later remarking that he was naive thinking he could do business honestly not realising that the police expected a bribe.

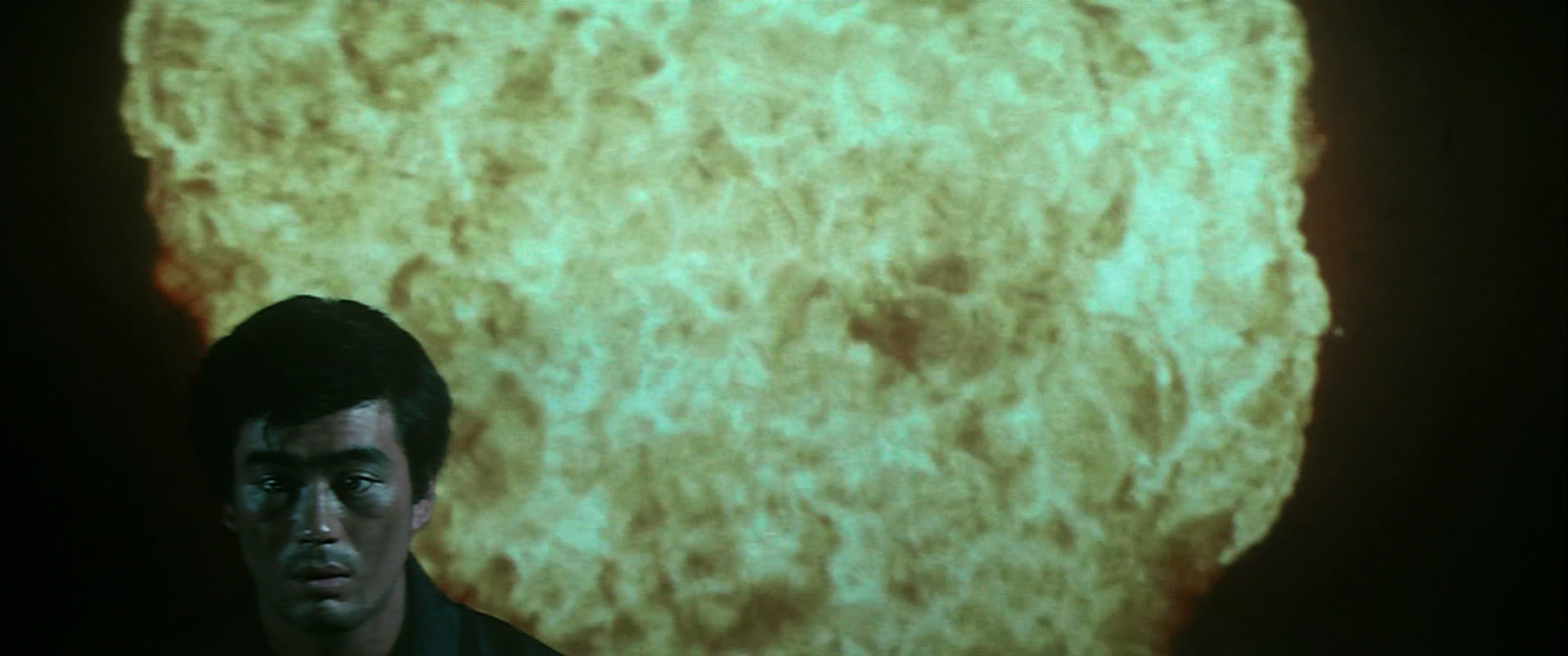

Tuberculosis and the death of a girl who like him could not afford medical treatment further leave Onuma feeling resentful and hopeless leading to a suicide attempt after which he is born again in Nichiren Buddhism and becomes a servant to Nissho. It’s easy to see how Nichiren could offer an escape to young men like him who burn with rage and a desire to change society, though in essence it’s no different from the militarism that was growing in parallel being rooted in nationalist ideology and for the early part at least centred in the military. The May 15 Incident saw the military and members of the League of Blood assassinate the prime minister to enact the Showa Restoration and reorganise society. The revolution failed, but the 11 young officers who took part in received little punishment, furthering cause of the militarism, while directly contributing to the February 26th Incident which though it also achieved little further cemented the power of the military over the government.

Though imperialism is subtly presented as another form of injustice as the nation spends money on warmongering while the people starve, the film straddles an awkward line in struggling to avoid glorifying the actions of the far right in painting Onuma and leader of the February 26th Incident Isobe (Koji Tsuruta) as dashing, idealistic heroes whose only wish was to save Japan and remake it in a way they believed to be better. This was pretty much the antithesis of what Nakajima intended, though it was picked up by some as a piece of right-wing propaganda. The film courted controversy both with Toei studio bosses and the government who ordered Nakajima to soften the excerpts from Isobe’s diary fearing they were too incendiary, though Nakajima had already shot the footage and was forced to find a compromise. Toei as a studio did rather lean towards the conservative and especially in its yakuza films which is perhaps unavoidable given that yakuza organisation did often have strongly nationalistic sensibilities. Accordingly, the film stars almost their entire roster of Toei’s yakuza and ninkyo eiga stars from Tomisaburo Wakayama to Ken Takakura and Koji Tsuruta along with Junko Fuji as as Onuma’s love interest who is eventually forced into sex work because of the economic conditions of the 1920s, and perhaps comes with some of that baggage. Its closing question, however, given the fact that all these assignations achieved almost nothing of what they were intended to, seems to be posited at the current society mired in the Anpo protests and the declining student movement to ask how else society might be changed and revolution enacted to create a fairer society for all through an ideology that could end this cycle of political violence.