“Vegetarian Men” became an unlikely buzzword in Japanese pop culture a few years ago. Coined by a confused older generation to describe a perceived decrease in “manliness” among young, urban males who had apparently lost interest in women and gained an interest in personal appearance as an indicator of social status, the term feeds into a series of social preoccupations from the declining birthrate and changing demographics to familial breakdown and economic stagnation. In an odd way, Bittersweet (にがくてあまい, Nigakute Amai) backs into this particular alley by adding an extra dimension in the story of a somewhat “manly” career woman and her non-romance with a gay vegetarian she meets by chance who eventually helps her to escape her arrested adolescence and progress towards a more conventional adulthood.

“Vegetarian Men” became an unlikely buzzword in Japanese pop culture a few years ago. Coined by a confused older generation to describe a perceived decrease in “manliness” among young, urban males who had apparently lost interest in women and gained an interest in personal appearance as an indicator of social status, the term feeds into a series of social preoccupations from the declining birthrate and changing demographics to familial breakdown and economic stagnation. In an odd way, Bittersweet (にがくてあまい, Nigakute Amai) backs into this particular alley by adding an extra dimension in the story of a somewhat “manly” career woman and her non-romance with a gay vegetarian she meets by chance who eventually helps her to escape her arrested adolescence and progress towards a more conventional adulthood.

Maki (Haruna Kawaguchi), an advertising agency employee and workaholic career woman in her late ‘20s, has a philosophical objection to the existence of vegetables. Unable to cook and generally disinterested in food (or house work, clothes, makeup etc), Maki sucks on jelly packs at her desk so she can keep on typing, sometimes treating herself to a store bought bento. She’s told her “friends” at work that she’ll shortly be moving in with a boyfriend, but in reality she’s recently broken up with someone and is being evicted from her flat. Things are looking up when she’s put in charge of a commercial but the commercial turns out to be for goya bitter melon which is both a vegetable and not exactly an easy sell.

Fast forward to a bar where Maki is a regular. After getting blind drunk and going off on an anti-vegetable rant, Maki wakes up at home with Nagisa (Kento Hayashi) – a guy she quite liked the look of the previous night but went off when she noticed he was carrying a giant box of veggies, making her a nutritious breakfast which she then refuses to eat. Paranoid that Nagisa took advantage of her in the night, Maki goes through his bag and discovers that he’s a high school art teacher. Challenging him about what exactly happened, he is forced to tell her that she’s not his type. Nagisa is gay and brought the blackout drunk Maki back to her flat on the instructions of his friend, the gay bartender at Maki’s local. Maki, classy as ever, threatens to blackmail Nagisa by outing him at school unless he agrees to move in with her.

Thankfully, Bittersweet drops the romance angle relatively quickly as Maki begins to grow up and accepts that there’s no point chasing a man who will never be interested in her. Nagisa, originally adopting an almost maternal attitude towards the sullen Maki, later becomes something like a big brother figure, gently coaxing his friend towards self realisation through a series of well cooked meals and hard won life advice. Though there is a degree of stereotyping in his refined, elegant personality, cleanliness, and cooking ability, Nagisa’s sexuality is never much of an issue outside of the obvious fact that he is not “out” at work and that it may be impossible for him to be so. Despite Maki’s original consternation she gets over the shock of Nagisa’s confession fairly quickly and when he eventually meets her parents, they too react with relative positivity (Maki’s mum even slips a copy of a BL manga into her next care package).

Somewhat bizarrely the central drama revolves around Maki’s hatred of vegetables which stems back to a stubborn resentment of her parents’ unconventionality. In combatting her parents’ decision to abandon the world of corporate consumerism, Maki has become a “career woman”, eschewing the feminine arts in favour of the male drive. Where Bittersweet was perhaps progressive in its acceptance of Nagisa’s sexuality, it is less so with Maki’s seeming “maleness” – her drinking, meat eating, and workaholic ambition all painted as aspects of her life which are in need of correction. Though some of her habits are undoubtedly unhealthy – she could definitely benefit from better nutrition and scaling back on the binge drinking, Bittersweet is intent on “restoring” Maki to the cuteness befitting the heroine of a shojo manga rather than allowing her to become a confident modern woman who can have both a career and a love interest with little conflict between the two.

Through meeting Nagisa Maki is able to get over her vegetable hate and repair her strained relationship with her comparatively more down to earth parents while also realising she doesn’t necessarily want the life of empty consumerism symbolised by her relationship with her status obsessed former boyfriend. Meanwhile Nagisa has his own problems in dealing with a past trauma which his new found, quasi-familial relationship with Maki is the key to addressing. A pleasant surprise, Bittersweet is not the awkward romance the synopsis hints at, but a warm and gentle coming of age story in which vegetarian cookery, mutual respect, and a lot of patience, allow two youngsters to become unstuck and find in each other the strength they needed to finally move forward into a more promising future.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo.

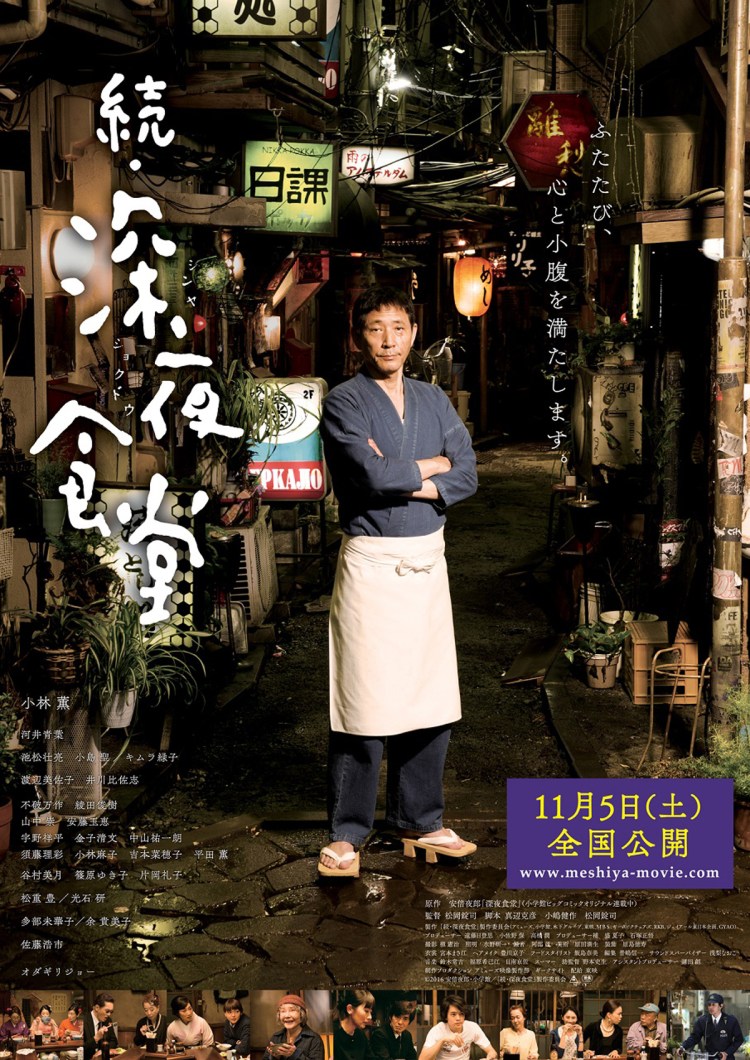

Hiroya Oku’s long running manga series Gantz has already been adapted as a TV anime as well as two very successful live action films from Shinsuke Sato. Gantz:O (ガンツ:オー) is the first feature length animated treatment of the series and makes use of 3D CGI and motion capture for a hyperrealistic approach to alien killing action. “O” for Osaka rather than “0” for zero, the movie is inspired by the spin-off Osaka arc of the manga shifting the action south from the regular setting of central Tokyo. The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

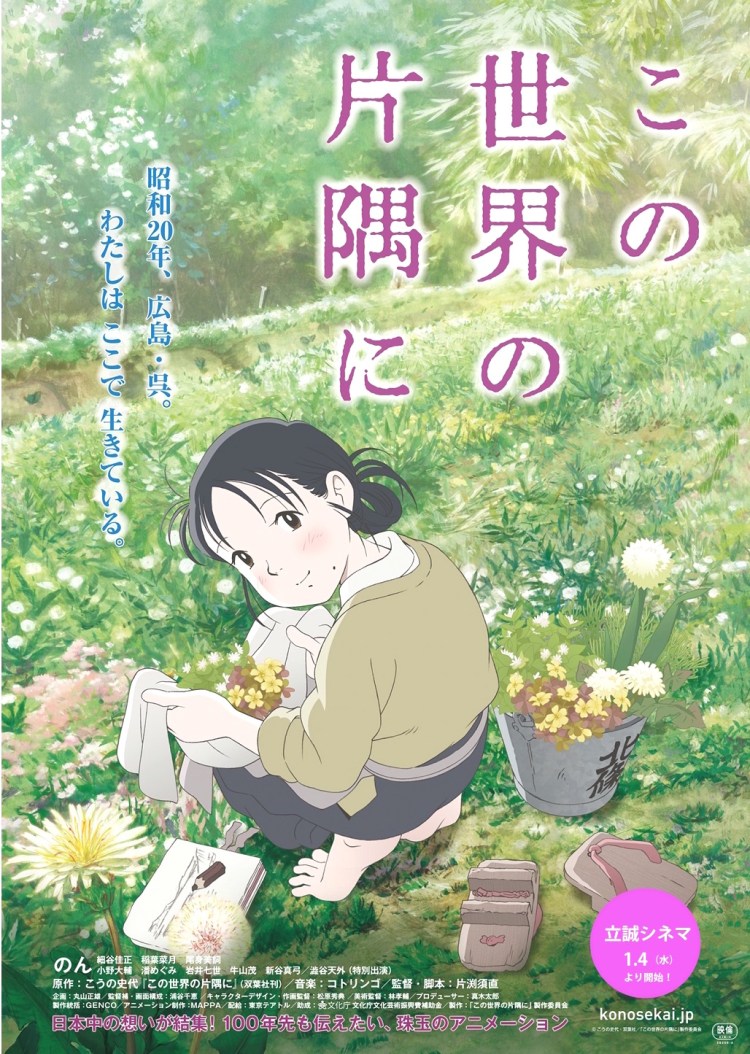

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the  Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times.

Depictions of wartime and the privation of the immediate post-war period in Japanese cinema run the gamut from kind hearted people helping each other through straitened times, to tales of amorality and despair as black-marketeers and unscrupulous crooks take advantage of the vulnerable and the desperate. In This Corner of the World (この世界の片隅に, Kono Sekai no Katasumi ni), adapted from the manga by Hiroshima native Fumiyo Kouno, is very much of the former variety as its dreamy, fantasy-prone heroine is dragged into a very real nightmare with the frontier drawing ever closer and the threat of death from the skies ever more present but manages to preserve something of herself even in such difficult times. Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness.

Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness. Fear of “broadcasting” is a classic symptom of psychosis, but supposing there really was someone who could hear all your thoughts as clearly as if you’d spoken them aloud, how would that make you feel? The shy daydreamer at the centre of The Kodai Family (高台家の人々, Kodaike no Hitobito) is about to find out as she becomes embroiled in a very real fairytale with a handsome prince whose lifelong ability to read minds has made him wary of trying to form genuine connections with ordinary people. Walls come down only to jump back up again when the full implications become apparent but there are taller walls to climb than that of discomfort with intimacy including snobby mothers and class based insecurities.

Fear of “broadcasting” is a classic symptom of psychosis, but supposing there really was someone who could hear all your thoughts as clearly as if you’d spoken them aloud, how would that make you feel? The shy daydreamer at the centre of The Kodai Family (高台家の人々, Kodaike no Hitobito) is about to find out as she becomes embroiled in a very real fairytale with a handsome prince whose lifelong ability to read minds has made him wary of trying to form genuine connections with ordinary people. Walls come down only to jump back up again when the full implications become apparent but there are taller walls to climb than that of discomfort with intimacy including snobby mothers and class based insecurities.