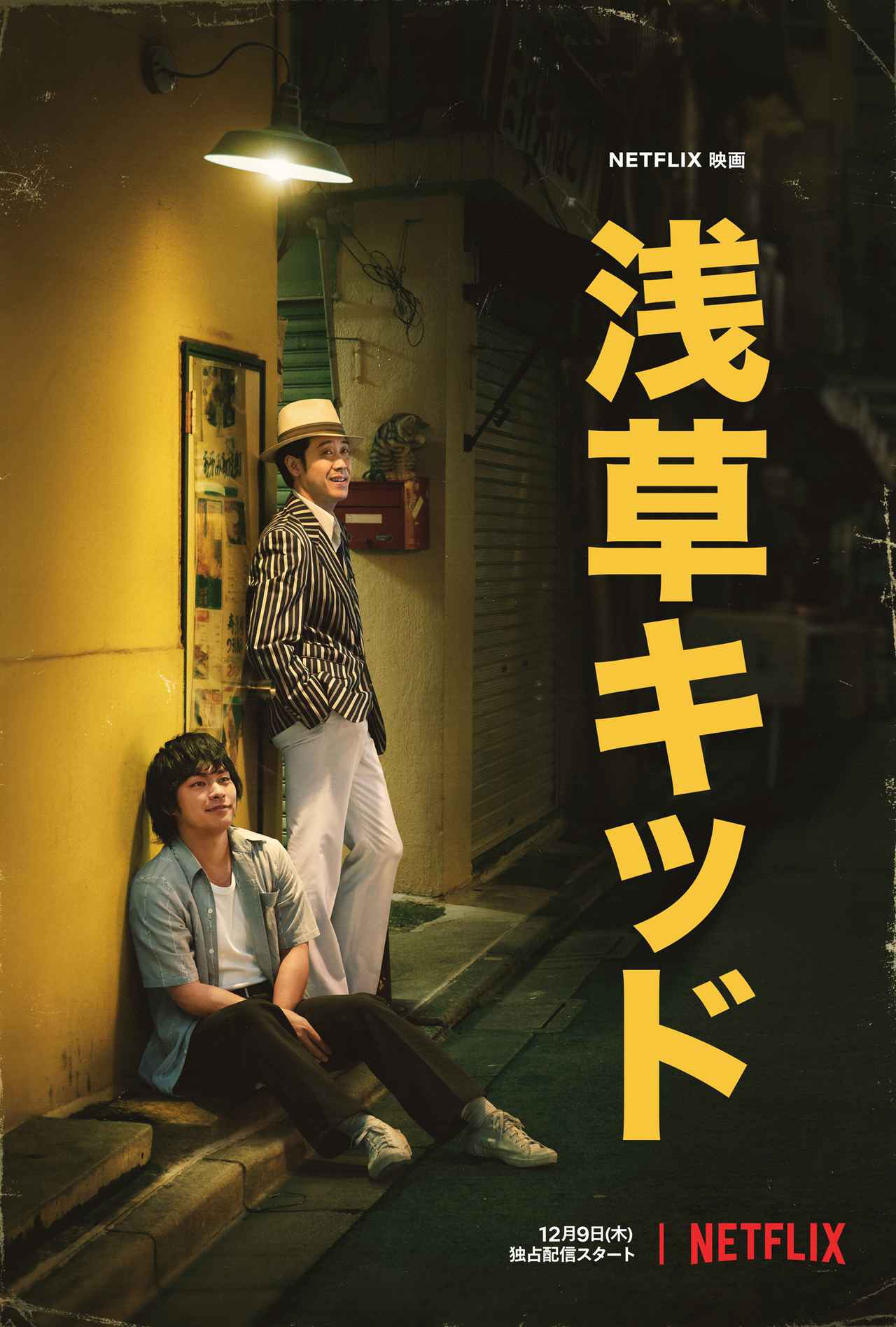

To international audiences, Takeshi Kitano has a very specific profile associated most closely with arthouse drama and violent gangster movies yet in Japan he’s best known as a comedian and TV personality. Inspired by Kitano’s memoir, Asakusa Kid (浅草キッド) charts his earliest days from entertainment district elevator boy to manzai star while lionising his earnest mentor Sozaburo Fukami (Yo Oizumi). Yet it’s also a nostalgic look back to a late Showa pre-bubble Japan as Kitano’s idol finds himself falling foul of a changing entertainment industry.

As the film opens in 1974, “Take” (Yuya Yagira) is one half of a struggling manzai comedy double act touring the country in various variety and cabaret establishments fearing his career may die out on the road before beginning to edge towards success and a high profile TV gig. Two years earlier, however, he’s an awkward college dropout working as an elevator boy at France-za comedy bar burlesque theatre. A local boy, Take has chosen France-za because of his admiration for “Fukami of Asakusa”, longing to make his way into the entertainment world while captivated by Fukami’s cool style, even copying his trademark tap dancing. Fukami soon sees talent in Take and tries to nurture it, but as the pair of them are repeatedly reminded, this kind of comedy is already old-fashioned. Audience numbers at France-za continue to decline while as one of the other girls later reminds him the men who come to these shows are there to see women take their clothes off, not random skits or singing.

This is brought home to Take when he tries to encourage one of the strippers, Chiharu (Mugi Kadowaki ), to chase her dreams of becoming a singer by convincing Fukami to allow her to fill a 15-minute spot. As Fukami had attempted to warn him, the men appear to enjoy her song and offer rapturous applause but think it’s part of her act and soon resort to catcalls expecting her to take her clothes off. Take’s well-meaning gesture backfires, convincing Chiharu her dreams of singing are over, while Take is also poked into action by the other stripper’s retort that the comedy is only really “filler” between the burlesque acts which is what the customers have come to see.

Even so, there’s less drama than one might expect in Take’s eventual decision to betray his mentor by choosing manzai and its opportunities for TV success over his by then old-fashioned sketch comedy. The father/son relationship somewhat falls by the wayside as even as a triumphant Take later returns “home” to present Fukami with the prize money for a TV award like a child with a report card full of As, while he gracefully accepts it but is privately filled both with a sense of pride and personal disappointment in being forced to accept that the heyday of Asakusa is over and there is no future in his vaudeville-style comedy acts. Nevertheless, Take appears to attribute much of his success to things he learnt from Fukami from his tap-dancing to his uncompromising attitude. “Don’t be laughed at, make them laugh,” he recalls Fukami telling him, “don’t suck up to the audience, tell them what’s funny,” later refusing to soften his inappropriate jokes about ugly girls and suicide for a more conservative TV audience and finding his edgy comedy an irreverent hit.

Then again, not everyone is able to achieve their dreams from Fukami who lost the fingers on one hand in the war and finds himself forced off the stage, to Chiharu apparently a regular housewife with showbiz regrets, and Fukami’s wife Mari (Honami Suzuki) exhausting herself trying to help him save his dream of Asakusa. As much as Take might have admired Fukami, others too describing him as a father of contemporary entertainment, he can’t get away from the fact the press is only interested in his funeral if Take attends it. Filled with the nostalgia, the ethereal one shot closing sequence in which the older Take returns to Asakusa and to the past surrounded by the friends of his youth is genuinely poignant in the sudden juxtaposition of a lost world with the contemporary present but perhaps elegises nothing so much as nostalgia in its lament for late Showa breeziness.

Original trailer (English subtitles)