For one reason or another, Japanese mystery novels have yet to achieve the impact recently afforded to their Scandinavian brethren. Japan does however have a long and distinguished history of detective fiction and a number of distinctive, eccentric sleuths echoing the European classics. Mitsuhiko Asami is just one among many of Japan’s not quite normal investigators, and though Noh Mask Murders (天河伝説殺人事件, Tenkawa Densetsu Satsujin Jiken) is technically the 23rd in the Asami series, Kon Ichikawa’s adaptation sets itself up as the very first Asami case file and as something close to an origin story.

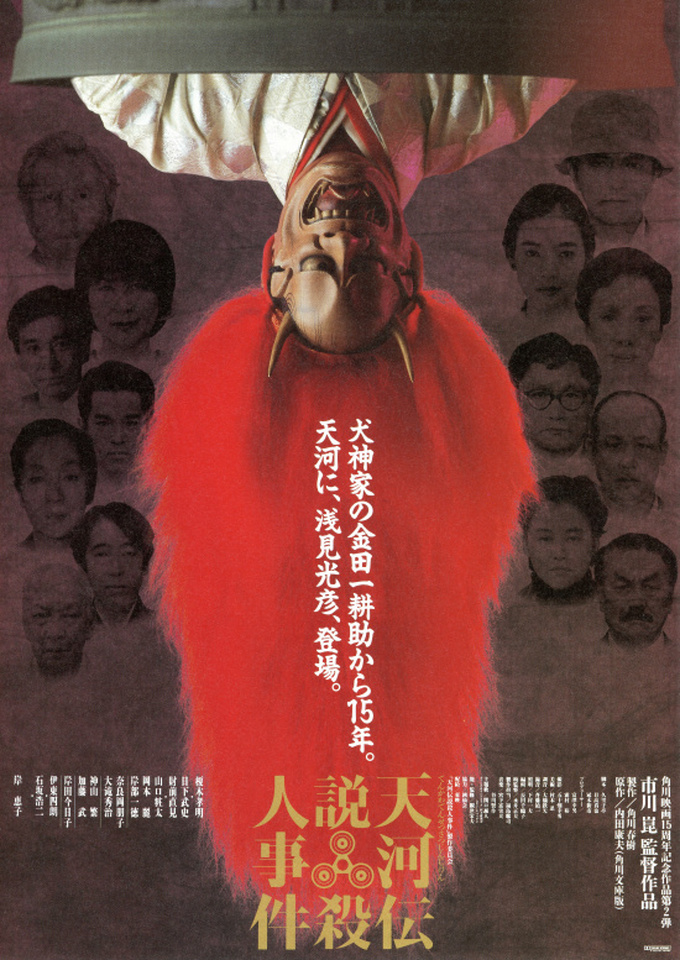

For one reason or another, Japanese mystery novels have yet to achieve the impact recently afforded to their Scandinavian brethren. Japan does however have a long and distinguished history of detective fiction and a number of distinctive, eccentric sleuths echoing the European classics. Mitsuhiko Asami is just one among many of Japan’s not quite normal investigators, and though Noh Mask Murders (天河伝説殺人事件, Tenkawa Densetsu Satsujin Jiken) is technically the 23rd in the Asami series, Kon Ichikawa’s adaptation sets itself up as the very first Asami case file and as something close to an origin story.

Ichikawa, though he may be best remembered for his ‘60s arthouse masterpieces, was able to go on filmmaking where others perhaps were not precisely because of his forays into the populist with a series of mystery thrillers including several featuring top Japanese detective Kindaichi (who receives brief name check in Noh Mask Murders). Published by Kadokawa, Noh Mask Murders is produced by Haruki Kadokawa towards the end of his populist heyday and features many of the hallmarks of a “Kadokawa” film but Ichikawa also takes the opportunity for a little formal experimentation to supplement what is perhaps a weaker locked room mystery.

Asami (Takaaki Enoki) begins with a voice over as four plot strands occur at the same temporal moment at different spaces across the city. In Shinjuku, a salaryman drops dead on the street, while a young couple enjoy a secret tryst in a secluded forest, a troupe of actors rehearse a noh play, and Asami himself is arrested by an officious policeman who notices him walking around with a dead bird in his hand and accuses him of poaching. As he will later prove, all of these moments are connected either by fate or coincidence but setting in motion a series of events which will eventually claim a few more lives before its sorry conclusion.

To begin with Asami, he is a slightly strange and ethereal man from an elite background who has been content to drift aimlessly through life to the consternation of his conservative family which includes a police chief brother. He harbours no particular desire to become a detective and is originally irritated by a family friend’s attempts to foist a job on him but gives in when he learns he will have the opportunity to visit Tenkawa which is where, he’s been told, the mysterious woman who helped him out with the policeman in the opening sequence keeps an inn. Hoping to learn more about her, he agrees to write a book about the history of Noh and then becomes embroiled in a second murder which links back to the Mizugami Noh Family which is currently facing a succession crisis as the grandfather finds himself torn over choosing his heir – he wants to choose his granddaughter Hidemi (Naomi Zaizen) who is the better performer but the troupe has never had a female leader and there are other reasons which push him towards picking his grandson, Kazutaka (Shota Yamaguchi).

As with almost all Japanese mysteries, the solution depends on a secret and the possibilities of blackmail and/or potential scandal. The mechanics of murders themselves (save perhaps the first one) are not particularly difficult to figure out and the identity of the killer almost certainly obvious to those who count themselves mystery fans though there are a few red herrings thrown in including a very “obvious” suspect presented early on who turns out to be entirely incidental.

Ichikawa attempts to reinforce the everything is connected moral of the story through an innovative and deliberately disorientating cross cutting technique which begins in the prologue as Ichikawa allows the conversations between the grandchildren to bleed into those of Asami and his friend as if they were in direct dialogue with each other. He foregrounds a sad story of persistent female subjugation and undue reliance on superstition and tradition which is indirectly to blame for the events which come to pass. Everyone regrets the past, and after a little murder begins to see things more clearly in acknowledging the wickedness of their own actions as well as their own sense of guilt and complicity. Noh is, apparently, like a marriage, a matter of mutual responsibility, fostering understanding between people and so, apparently is murder, and one way or another Asami seems to have found his calling.

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

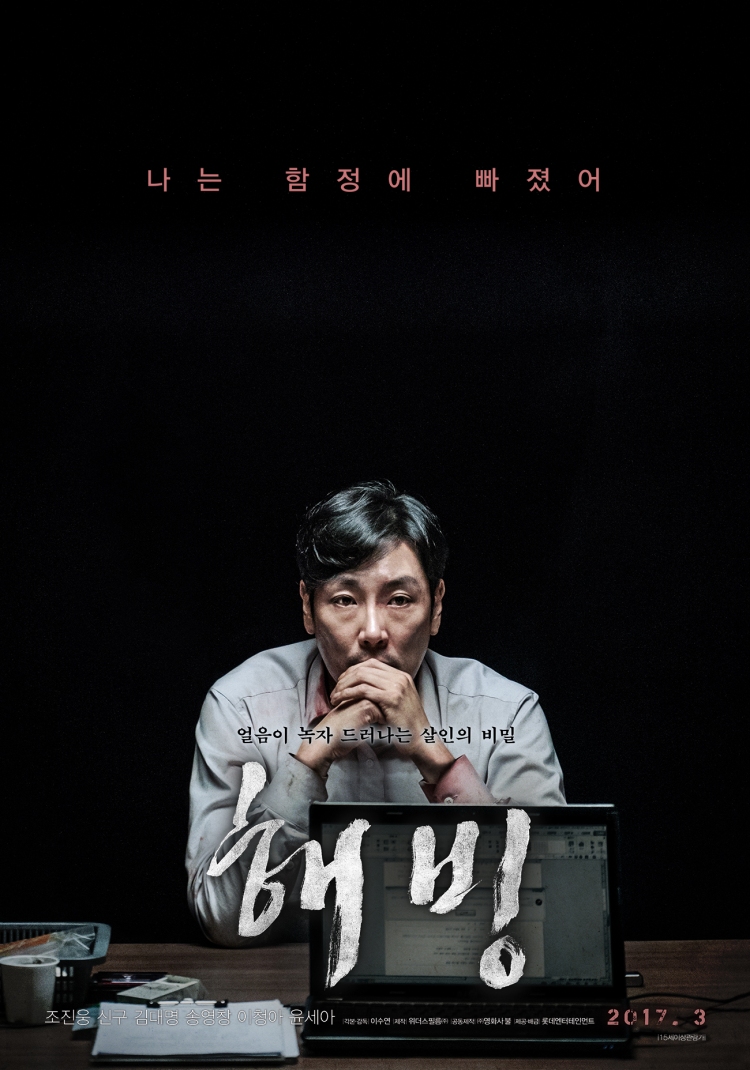

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society. If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects.

If you think you might have moved in above a modern-day Sweeney Todd, what should you do? Lee Soo-youn’s follow-up to 2003’s The Uninvited, Bluebeard (해빙, Haebing), provides a few easy lessons in the wrong way to cope with such an extreme situation as its increasingly confused and incriminated hero becomes convinced that his butcher landlord’s senile father is responsible for a still unsolved spate of serial killings. Rather than move, go to the police, or pretend not to have noticed, self-absorbed doctor Seung-hoon (Cho Jin-woong) drives himself half mad with fear and worry, certain that the strange father and son duo from downstairs have begun to suspect that he suspects. Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.

Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story. Kon Ichikawa may be best remembered for his mid career work, particularly his war films The Burmese Harp and

Kon Ichikawa may be best remembered for his mid career work, particularly his war films The Burmese Harp and  Yusaku Matsuda was to adopt arguably his most famous role in 1979 – that of the unconventional private detective Shunsaku Kudo in the iconic television series Detective Story (unconnected with the film of the same name he made in 1983), but Murder in the Doll House (乱れからくり, Midare Karakuri) made the same year also sees him stepping into the shoes of a more conventional, literature inspired P.I.

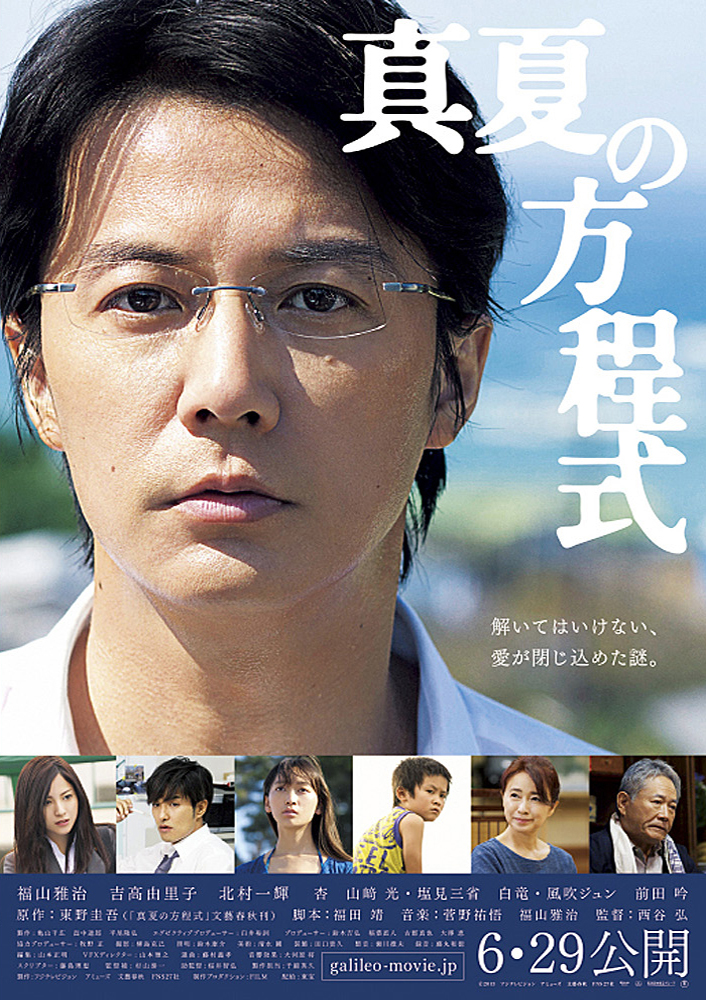

Yusaku Matsuda was to adopt arguably his most famous role in 1979 – that of the unconventional private detective Shunsaku Kudo in the iconic television series Detective Story (unconnected with the film of the same name he made in 1983), but Murder in the Doll House (乱れからくり, Midare Karakuri) made the same year also sees him stepping into the shoes of a more conventional, literature inspired P.I. Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.