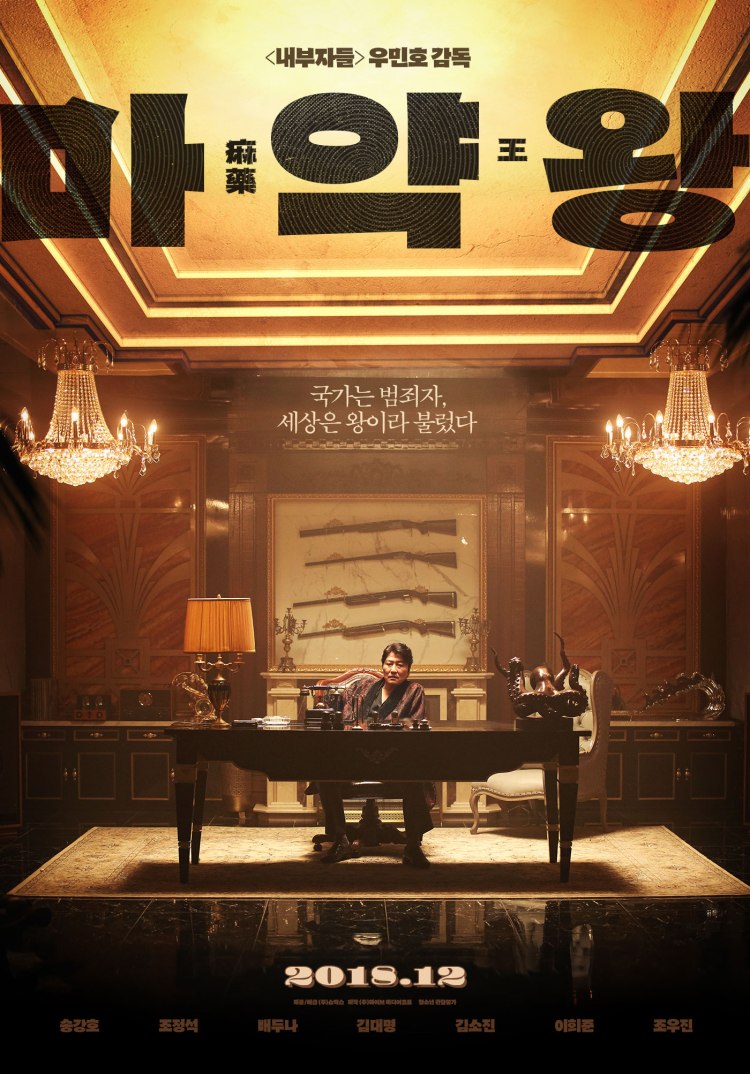

Korean cinema has been in a reflective mood of late, keen to re-examine the turbulent post-war era in the wake of a second wave of democratic protest and political turmoil. Even so, dealing with the difficult Park Chung-hee era has remained sensitive with the legacy of life under a repressive regime apparently very much still felt. Woo Min-ho’s Drug King (麻藥王 / 마약왕, Mayakwang) is first and foremost a crime doesn’t pay story, but it’s also a subtle condemnation of authoritarianism and the corruption and cronyism that goes along with it. Painting its hero’s rise as a consequence of the society in which he lives, it perhaps implies the new wind of egalitarian democracy made such amoral venality a thing of the past but then again is at pains to show that nothing really changes when it comes to greed and resentment.

Korean cinema has been in a reflective mood of late, keen to re-examine the turbulent post-war era in the wake of a second wave of democratic protest and political turmoil. Even so, dealing with the difficult Park Chung-hee era has remained sensitive with the legacy of life under a repressive regime apparently very much still felt. Woo Min-ho’s Drug King (麻藥王 / 마약왕, Mayakwang) is first and foremost a crime doesn’t pay story, but it’s also a subtle condemnation of authoritarianism and the corruption and cronyism that goes along with it. Painting its hero’s rise as a consequence of the society in which he lives, it perhaps implies the new wind of egalitarian democracy made such amoral venality a thing of the past but then again is at pains to show that nothing really changes when it comes to greed and resentment.

Our hero, Lee Doo-sam (Song Kang-ho), starts out as a jeweller dabbling in smuggling in Busan in 1972. Just as the smuggling business starts to take off, Doo-sam’s boss falls out with his friends in high places and decides to throw him to the wolves while he escapes abroad to safety. Doo-sam, not one to be beaten, starts coming up with ideas. Mobilising his wife (Kim So-jin) to get him out of jail through a combination of bribery and blackmail, he teams up with the area’s smuggling king to act on a tip-off he got from a Korean-Japanese yakuza and begins producing popular drug Crank for export to Japan.

As the opening voice over explains, Crank is a dangerous stimulant developed by the Japanese during the war and given to factory workers and kamikaze pilots because of its ability to eliminate both fear and fatigue. It is also highly addictive and provides an extreme high which have made it a popular recreational drug but, crucially, the real value is economic. The rising Japan is keen to make use of foreign labour, and Korea is keen to up its export capability. This, coupled with poor regulation of the workforce, has led to extreme exploitation in which factory workers are encouraged to hop themselves up on stimulants to keep working overtime for the sake of economic expansion. Thus, the influx of Crank is, in many ways, simply another facet of ongoing Japanese imperialism.

Not that Lee Doo-Sam cares very much about that. An honest prosecutor later puts it to him that he’s contributing to the exploitation of ordinary workers who might earn a few pennies extra for working a few more hours but at the cost of their health and wellbeing, while he gets filthy rich off the back of their misery. Doo-sam is, however, unrepentant. In the beginning he just wanted to provide for his wife, children, and unmarried sisters, but perhaps he also wanted to kick back against his reduced circumstances and he certainly did enjoy playing the big man. In any case, it has paid off. Doo-sam too has friends in high places and they won’t want to let him sit in a police cell for long in case he starts feeling chatty.

Times change, however, and whatever standing and influence Doo-sam thought he’d accrued his life is built on sand. When Park is assassinated by a member of his own security team, all those contacts are pretty much useless because the cronies are now out in the cold. There are protests in the streets and the wind of a new era is already blowing through even if it is still a fair few years away. That bold new era will, it hopes, do away with men like Doo-sam and their way of thinking, eradicating corruption and backhanders in favour of honest meritocracy. Naive, perhaps, and idealistic but it is true enough that Doo-sam is a man whose era has passed him by while he, arrogantly, burned all his bridges and gleefully sacrificed love and friendship on the altar of greed and empty ambition.

Hubris is Doo-sam’s fatal flaw, but he remains a weasel to the end only too keen to sell out his associates in order to save his own skin. He may claim he was only trying to live a “decent” life, but his definition of “decent” may differ wildly from the norm. Nevertheless, perhaps he was just like many scrappy young men of post-war years, desperate, hungry, and left with few honest options to feed his family if one who later found himself corrupted by backstreet “success” and the dubious morals of the world in which he lived which encouraged him to disregard conventional morality in favour of personal gain. Much more about life in Korea in the authoritarian ‘70s than it is about crime, The Drug King is nevertheless an ironic tragedy in which its drug peddling hero eventually enables the birth of a dedicated narcotics squad and helps to dismantle system which allowed him to prosper all while grinning wildly and, presumably, planning his next move.

Currently available to stream online via Netflix in the UK and possibly other territories.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Key tracks from the (fantastic) soundtrack:

Jung Hoon-Hee – Flower Road

Kim Jung Mi – Wind