Japan has famously tough immigration law and surprisingly robust labour protections though enforcing them often proves difficult. The plight of undocumented migrant workers can however be stark as Akio Fujimoto’s Along the Sea (海辺の彼女たち, Umibe no Kanojotachi) makes plain. The three women at the film’s centre, originally from Vietnam, came to Japan legally as part of the government-backed Technical Intern Training Program set up in the early ‘90s supposedly to provide temporary training opportunities for workers from developing economies. Perhaps inevitably, the scheme has often come in for criticism that it amounts to little more than legalised people trafficking allowing employers to maintain exploitative working practices while hiring cheap foreign labour and placing the so-called interns into positions which offer no real technical training.

This is very much the experience of Phuong (Hoang Phuong), Nhu (Quynh Nhu), and An (Huynh Tuyet Anh), three women in their early 20s who decide to leave their placement because of untenable exploitative conditions requiring them to work 15-hour days with little provision for meals or rest and no payment of overtime. Little different from traffickers, the employers have also held onto the women’s documentation in an attempt to prevent them leaving. The result of this, however, is that they will be living in Japan essentially illegally and without any kind of paperwork at all making it extremely difficult to return to Vietnam.

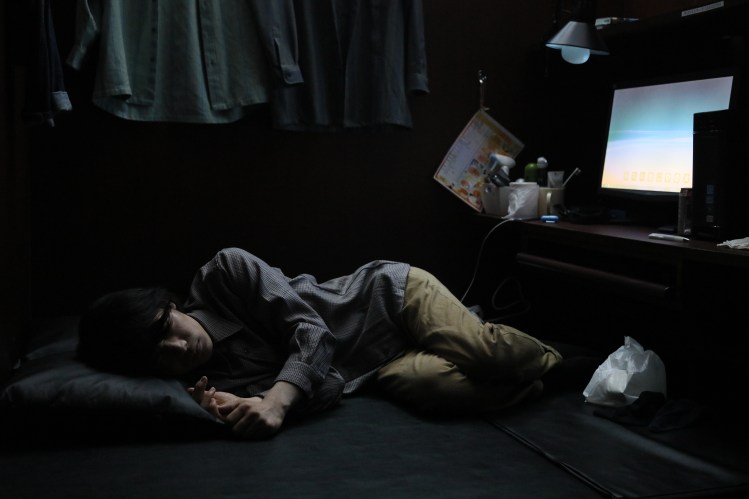

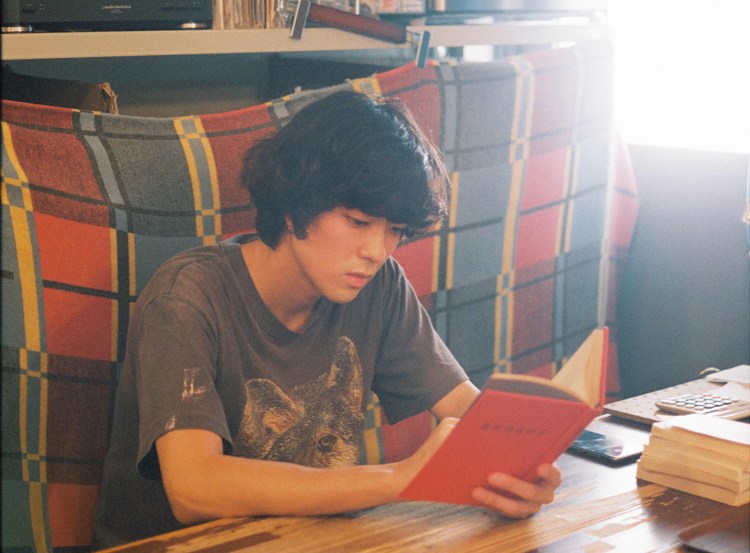

Fujimoto opens with the women’s nighttime escape, a perilous journey carrying heavy bags through the night until reaching a train station and then on to buses and ferries to the frozen north of Japan where they are met by a man in a van who takes them to their new place of employment, a fish packing warehouse in Aomori. Though the work is physically strenuous, the payment is much higher than they were previously receiving and paid on time, and the conditions are much more like a regular job with more reasonable hours including weekends off. They are not watched and have a much greater degree of freedom but are obviously nervous of discovery and prevented from participating in certain activities owing to having no ID. This becomes a particular problem for one of the women, Phuong, who has begun feeling ill but is unable to get medical treatment without some kind of documentation to show hospital staff.

What Phuong hasn’t shared with the other two women is that she suspects she may be pregnant by her hometown boyfriend. During their escape there had existed between them a fierce solidarity and now in a sense they have only each other to rely on, otherwise entirely alone in a foreign land. Phuong’s pregnancy revelation however drives a wedge between the women with Nhu in particular quickly losing sympathy and heavily pressurising her towards an abortion less out of concern and practicality than fear that she may give them all away. The later conclusion can only be that one or both of the women has betrayed Phuong by telling the broker about her pregnancy further piling on the pressure and almost certainly destroying the only support network the women had through an irreparable breach of trust.

Turned away by the hospital Phuong resolves to buy fake documentation only to be exploited once again by a fixer who suddenly demands more money forcing her to trek through the frozen countryside after losing her train fare home. Like the broker, who is actually nice, polite, and considerate (to a point) in his treatment of the women, the fixer is also Vietnamese a reminder that the women are in a sense being exploited by their fellow countrymen. One of the broker’s chief concerns is obviously that he’s taking 10% of the women’s pay on top of his original commission on finding the work and therefore he loses out if Phuong is unable to work during her pregnancy while childcare is also incompatible with her current lifestyle. Compounding the problem is the fact that each of the women is working to provide not for themselves but for their families meaning that Phuong is in no way free to simply decide to go home and raise her child. Cheerfully discussing what they’d like to do if they had more money, Nhu and An want to pay off their parents’ debts and provide for their siblings’ education. Phuong’s predicament affects more than just the lives of the three women and it seems they are not above forcing her hand in order to protect the better life they’re suffering to provide for their families.

A melancholy character study, Fujimoto’s unflinching drama follows Phuong with documentary precision towards an almost inevitable conclusion as she finds herself hemmed in by the demands of others entirely unable to act on her own desires while denied basic rights and freedoms by virtue of her lack of documentation. Shining a light on the all too hidden lives of migrant workers, Along the Sea paints a bleak picture of the contemporary society in which even solidarity can be broken by the cruel desperation of those who have nothing else on which to depend.

Along the Sea screened as part of the 2021 Osaka Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)