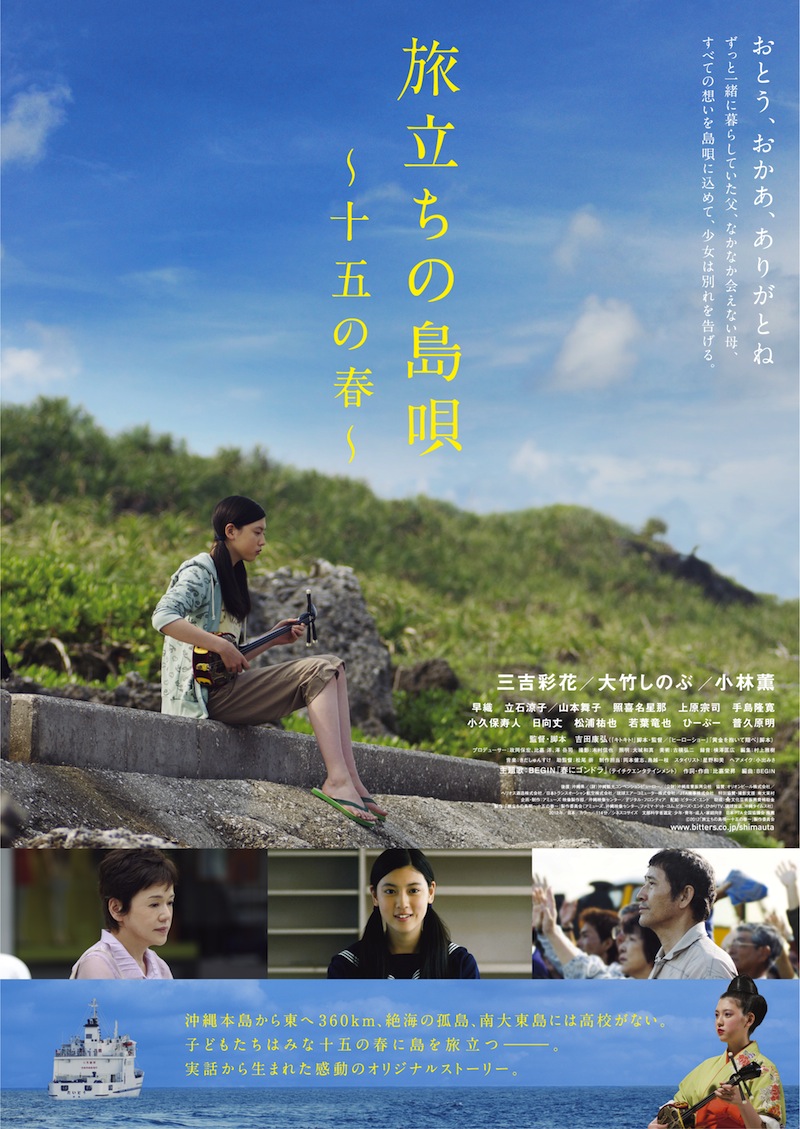

“How many of them will come back?” a man on the shore ominously asks as he watches the young people of his island ship out to pursue their education in the comparatively better equipped capital. Rural depopulation has become a minor theme in recent Japanese cinema, but the situation is arguably all the worse in the outlying islands of Okinawa. As the title of Yasuhiro Yoshida’s Leaving on the 15th Spring (旅立ちの島唄~十五の春~, Tabidachi no Shima Uta: Jugo no Haru) suggests, teens from the small island of Minami Daito (South Daito) must leave at 15 if they want to attend high school because there isn’t one on the island.

That said, there are more kids than you’d expect in young Yuna’s (Ayaka Miyoshi) middle school and it’s more than just a handful who leave the island each spring, many of them choosing to make lives for themselves in the wider world rather than return to their childhood home. On Minami Daito, the main industry is sugarcane but the prospect of Japan joining the TPP trade agreement has many worried that it will soon no longer be viable and with even fewer economic opportunities available many will have no choice other than to abandon the island for good.

We’re often reminded just how far the island is from the Okinawan capital Naha and how difficult it is to get to. To leave, the kids are placed in a kind of cage and lifted onto a larger boat moored by a small jetty. Even to get to the next island Kita Daito (North Daito) it’s some time on a ferry which might not run if the weather is bad. Distance becomes a persistent theme, not just in Yuna’s impending exit but the scattering of her family. When kids leave for high school, a parent often goes with them as Yuna’s mother Akemi (Shinobu Otake) did when it was time for her sister Mina (Saori) to depart. But Mina is now a grown woman married with a child of her own and Akemi has not been back to the island for two years. This forcible separation continues to disrupt familial bonds as couples necessarily grow apart and children begin to choose their own paths in life which often take them away from their parents.

It’s this sense of distance which plays on Yuna’s mind, a kind of countdown starting inside her as she witnesses another girl sing the Okinawa folk song “Abayoi” which means “goodbye” in the local dialect and recounts a young person’s sorrow as they must leave their family and childhood home behind on coming of age. Reminded that she’s next in only a year’s time, Yuna meditates on her past and future while reconsidering her relationships. Abandonment often occurs through a simple lapse in contact. Akemi now rarely phones home while Yuna’s nascent first love with a boy from Kita Daito falters when he abruptly stops calling or returning her letters. Eventually she finds out that despite their pledge to attend the same high school on Naha, he has decided to stay and take over his father’s fishing boat because of his dad’s ill health.

Kenta has realised that his place is Kita Daito and he will remain there the rest of his life while harbouring a degree of resentment that he couldn’t go to high school or pursue his romance with Yuna. He feels their relationship is doomed simply from the fact that they’re from different islands. He won’t leave his, and she likely would not settle on Kita Daito preferring, either a life in the cities or her childhood home. It’s the same for her parents, Akemi deciding that she prefers life in the city and the degree of independence she has there while her father Toshiharu (Kaoru Kobayashi) would not survive off the island. Both of her siblings have already left, Mina returning with her infant daughter apparently on the verge of separating with her husband partly it seems because of the insecurity the separation of her family has left her with, while Yuna’s brother seems to be a harried workaholic with no family life to speak of.

Rather childishly she thinks she can reunite her family and dreams of buying a big house on Naha for them all to live together, adult siblings included, without fully accepting that the relationship between her parents has been gradually worn away leaving them strangers to each other and each desiring different kinds of futures. What she comes to is perhaps an acceptance of the distance in her life, the longing for her island home where she says everyone is one big family, as she finds herself choosing independence. A picturesque vision of Minami Daito and its idyllic landscape along with the traditions of the island including its rich musical culture and Okinawan Sanshin, Yoshida’s gentle drama discovers that “abayoi” is a part of life that can’t be avoided but can be sweet as well as bitter once you’ve learned to accept it.

Trailer (English subtitles)

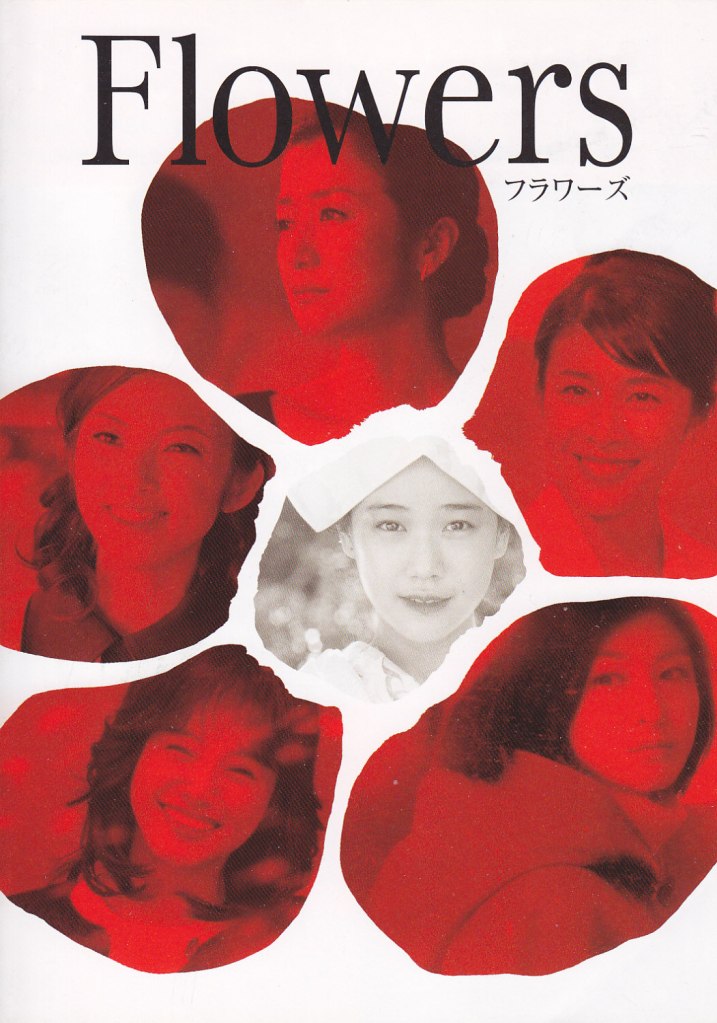

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point. Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.

Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.