Many of Mikio Naruse’s most famous films are adapted from the work of Fumiko Hayashi, a pioneering female author who chronicled the life of a working class woman with startling frankness. Yet his dramatisation of her life, A Wanderer’s Notebook (放浪記, Horo-ki), is both a little more reactionary than one might have expected and surprisingly unflattering even in the heroine’s eventual triumph in escaping her poverty through artistry. Even so if perhaps sentimentalising the economically difficult society of the 1920s in emphasising the suffering which gave rise to Hayashi’s art, the film does lay bare the divisions of class and gender that she did to some extent transgress in pursuit of her literary destiny.

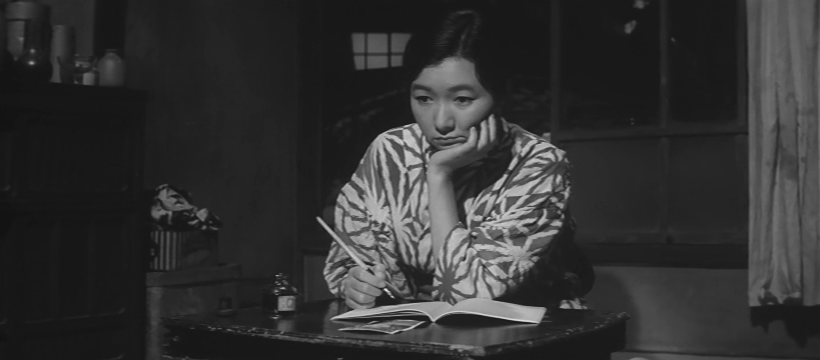

Naruse and his screenwriters Toshiro Ide and Sumie Tanaka bookend the the film with a literal “lonely lane” which the young Fumiko walks with her itinerant salespeople parents. As a small child, she sees her father arrested for a snake oil scam peddling some kind of wondrous lotion, setting up both her disdain for men in general and her determination not to be deceived by them at least unwittingly. She has no formal education but is a voracious reader well versed in the literary culture of the time and intensely resentful of if resigned to her poverty. In the frequent sections of text which litter the screen taken directly from her novels, she details her purchases, wages, and longing for the small luxuries she can in no way afford.

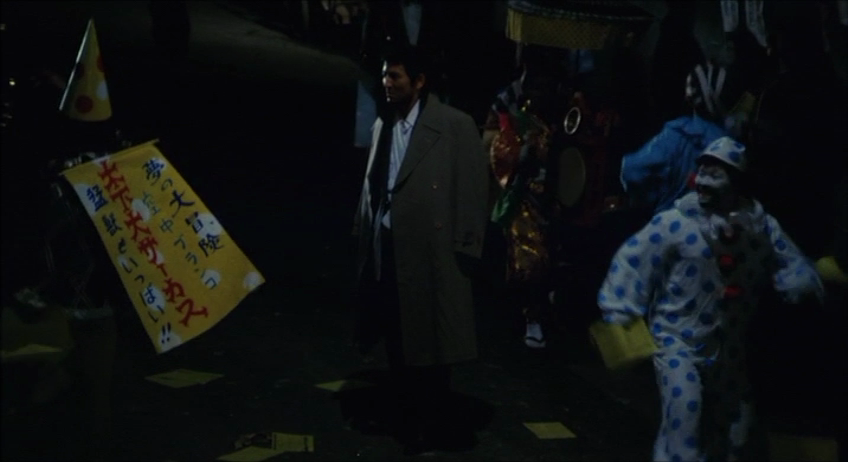

As an uneducated woman in the 1920s her working opportunities are few. She exasperatedly relates standing in a queue with hundreds of other women waiting for an interview for a company job only to be told they’ll let her know, while her other opportunity involves meeting a theatre director at a station who later takes her to his hotel/office and makes it plain he’s not really interested in her CV. She gets a job at the office of a stockbroker, but lies about being able to do accounts and is flummoxed by double entry bookkeeping getting herself fired on day one. After a brief stint in factory painting toys, she leaves with a friend to become a hostess but is also fired on her first day for getting drunk and being unwilling to ingratiate herself with the boorish men who frequent such establishments.

Despite her animosity, she is drawn towards men who are callous and self-involved, firstly taking up with a poet and actor who praises her work but turns out to have several “wives” on the go, and then begins living with a broody writer, Fukuchi, who is insecure and violent, resentful at her success in wake of his failure. Perhaps because of her experiences, she seems to resent any hint of kindness though sometimes kind herself, lending money to her friend whose mother is in need and often ready to stand up for others whom she feels are being mistreated. A kindly widower in the boarding house where she lives with her mother, Yasuoka, falls in love with her but she repeatedly rejects him partly as someone suggests because he is not handsome, but mainly because of his goodness and kindness towards her. Nevertheless, he continues to support always ready in her time of need though having accepted that she will never return his feelings or accept his proposal.

Perhaps her might have liked to have been kinder, but was too wounded by her experiences to permit herself. In any case at the film’s conclusion in which she has achieved success and in fact become wealthy it appears to have made her cold and judgemental. She instructs her maid to send a man away believing he is from a charity set up to help the poor, insisting that the poor must work for industry is the only path out of poverty implying that as she managed it herself those who cannot are simply not applying themselves when she of all people should know how fallacious the sentiment is. As if to bear out the chip on her shoulder, she forces her mother to wear a ridiculous kimono from a bygone era that is heavy for an old woman and makes her feel foolish because of her own mental image of the finery she dreamed of providing her on escaping the persistent hardship of their lives.

As she says, she’s no interest in the socialist politics espoused by the literary circles in which she later comes to move, pointing out that the poor have no time for waving flags. One of her greatest supporters is himself from a noble family despite his progressive politics and in truth can never really understand the lives of women like Fumiko. He describes her work as like upending a rubbish bin and poking through it with a stick, at once fascinated and repulsed by a frankness he may see as vulgar. At one point he accuses her of writing poverty porn, playing on her humble origins for copy and becoming something of a one note writer.

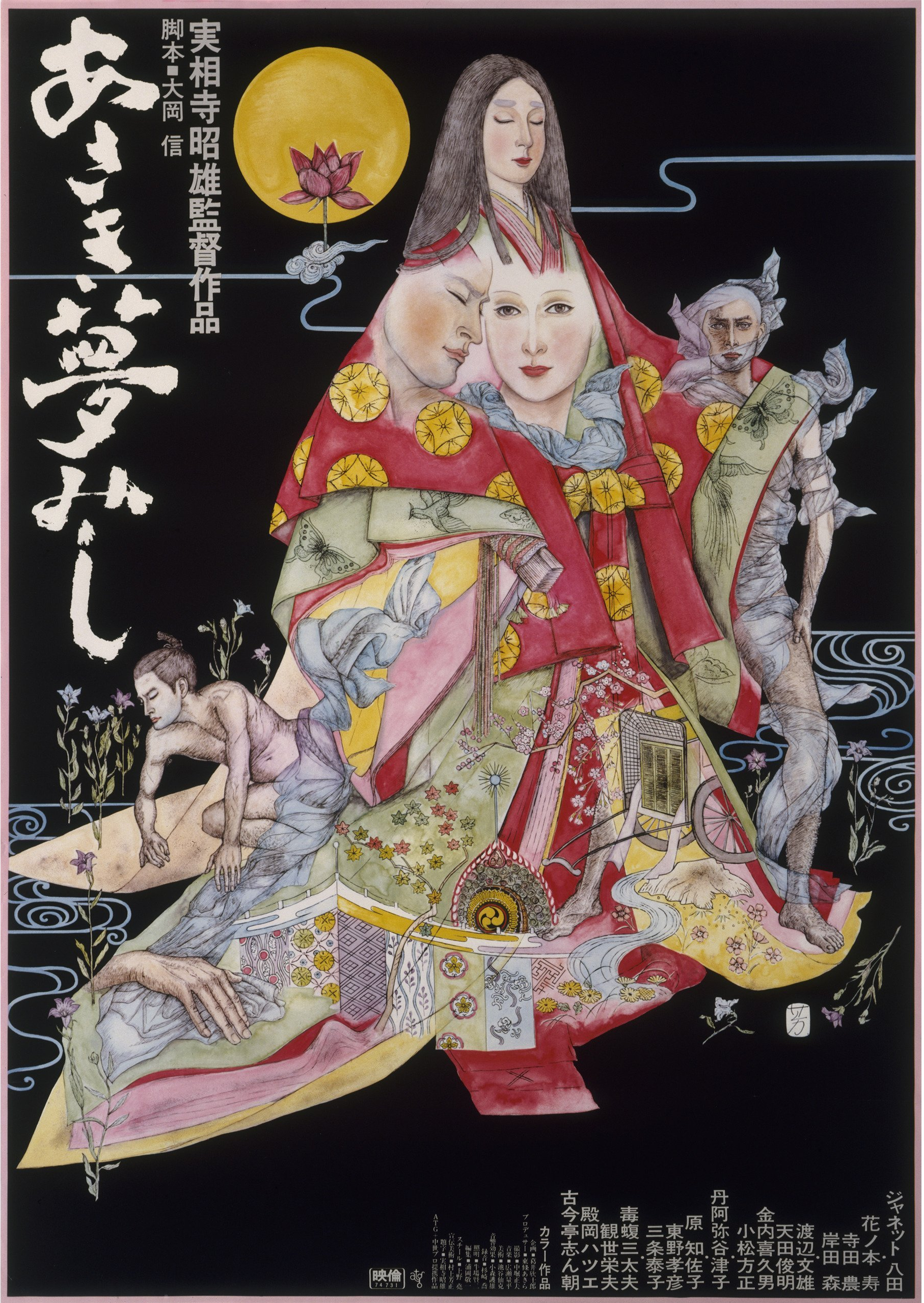

In truth, the film is not really based on the novel from which it takes its title but on the play that was adapted from it, while the novel itself was apparently reworked and republished several times in response to reader taste giving rise to a series of questions both about its essential authenticity and what it was that it was attempting to convey. In the film at least, moments after her literary success, Fumiko is challenged by a fellow female writer, Kyoko, who was once her love rival, that she cheated in a contest by failing to submit Kyoko’s entry until after the deadline had passed, though as it seems she would have won anyway. She is occasionally underhanded, perhaps because she feels she has no other choice, but then as we can see there is no particular solidarity between women save the kindly landladies who often let her delay her rent payments. Fumiko feels herself to be alone and her quest is not really for literary success but simply for her next meal, though she feels the slights of the bitchy women and arrogant men who mock her commonness while simultaneously exploiting it as entertainment.

On the one hand, her success seems to signal a triumph of independence having freed herself from the need to depend on terrible men though she also she seems to have met and married a warmhearted painter who cares for her and supports her work while she has also been able to give her mother the level of comfort they both once dreamed of. Even so, the unavoidable fact that she dies at such a young age implies she’s worked herself into an early grave in a sense punishing her for her rejection of contemporary social norms undercutting her achievements with some regressive moralising while the one thing she still desires, rest, is given to her only in death. In Takamine’s highly stylised performance, as some have implied perhaps intended to mimic the silent screen, Fumiko is at once a carefree young woman who dances and sings and a melancholy fatalist with a self-destructive talent for choosing insecure and self-involved men, but above all else a woman walking a lonely road towards her own fulfilment while searching for a way out of poverty that need not transgress her particular sense of righteousness.

Original trailer (no subtitles)