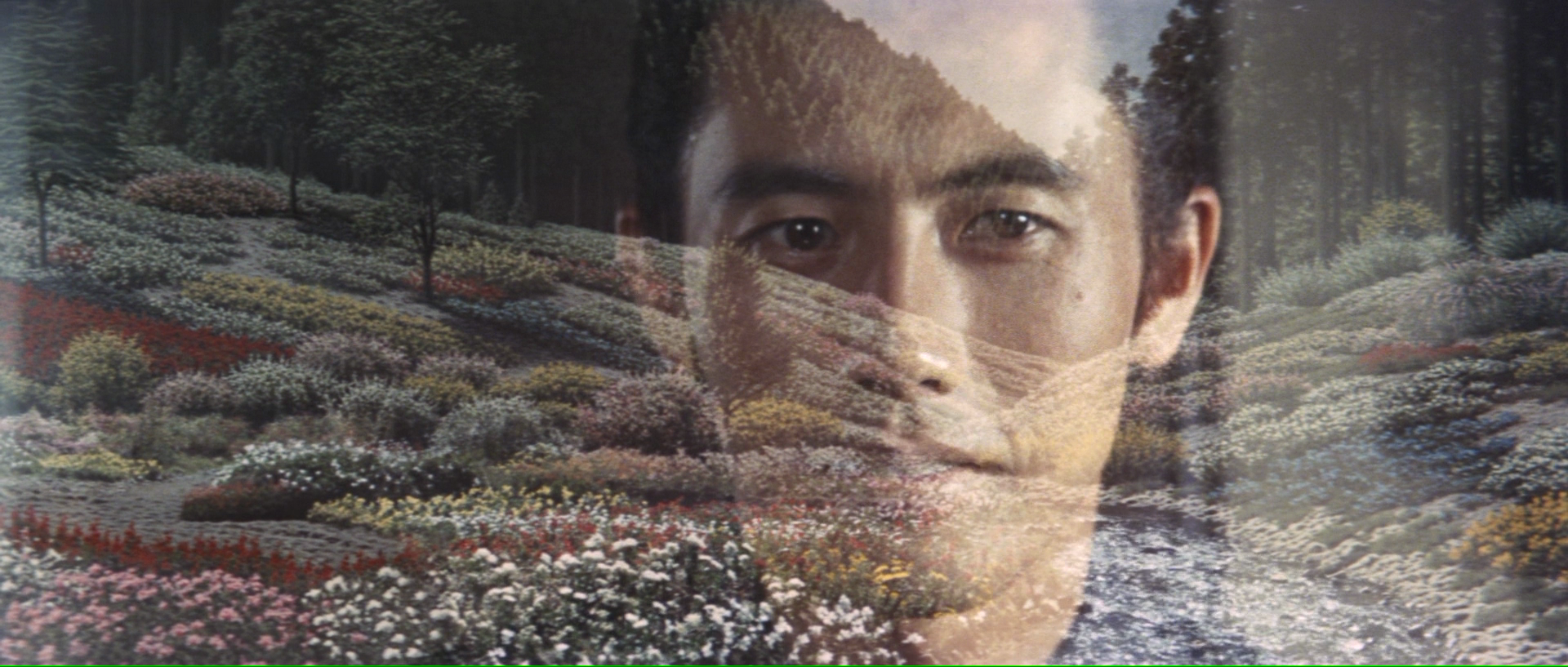

The abiding constant of the Shinobi Mono series had been its continual forward motion, at least up until instalment seven which had backtracked to the death of Ieyasu. This eighth and final film (save for a further sequel released in 1970 starring Hiroki Matsukata replacing Raizo Ichikawa who had sadly passed away a couple of years earlier at the young age of 37) however reaches even further back into the mists of time setting itself a few years before the original trilogy had begun.

This time around, we follow young Kojiro (Raizo Ichikawa) on what is a more stereotypical tale of personal revenge albeit that one that eventually becomes embroiled in politics as he joins a ninja band that’s working for Takeda Shingen (Kenjiro Ishiyama). In slightly surprising turn of events, Ieyasu (Taketoshi Naito) turns out to be what passes for a good guy at least in contrast to Shingen’s duplicity though Ieyasu himself is still young and at the very beginning of his military career which is why unlike his older self he’s a little more proactive and willing to start a fight as well as finish one. In any case, Shingen thinks he’s an easy target largely because he simply hasn’t been in post long enough to have begun making connections with local lords, bribing them with gifts to secure their loyalty.

In any case, Kojiro’s journey begins as something more like a martial arts film as he surpasses his current teacher and is told to find a man called Sadayu (Yunosuke Ito) in the mountains if wants to be up to gaining his revenge against the three men who killed his father while trying to steal his gunpowder. Perhaps there’s something a little ironic in the fact that Kojiro’s father was killed in a fight over what amounts to the substance of the future engineering a wholesale change in samurai warfare and edging towards the oppressive peace of the Tokugawa shogunate. But to get she revenge, Kojiro commits himself to learning true ninjutsu as the film demonstrates in a lengthy training montage. Unlike previous instalments, however, there is left emphasis place on the prohibition of emotion with the reason Kojiro cannot romance Sandayu’s adopted daughter down to her father’s whim forbidding her from marrying a ninja.

Apparently not the Sandayu of the earlier films despite the similarity of the name, this one has decided to side with Shingen because he’s mistakenly concluded that he is a “fair person who understands us ninja” when in reality he just using them and is no better than Nobunaga or Ieyasu. Shingen hires them to tunnel into a castle through the well, but is entirely indifferent to their complaints about safety leaving a Sandayu voiwing vengeance. The ninja, he says, generally serve themselves and are bound to no master but he seems to have thought Shingen was different only to be proved wrong once again.

Of course, Kojiro continues looking for the men who killed his father though they obviously guide him back towards conflict anyway. When he tracks some of them down, one remarks that all he did was finish him off which was an act of kindness to end his suffering not that he necessary approved of what his fallow gang members had done. Kojiro finds a surrogate father in Sadayu much as Goemon had though this time a slightly better one even if Sandayu is also a man with a lot on his conscience. Even more so than the other films, this one takes place in a largely lawless land too consumed with perpetual warfare to notice the starving and the desperate let alone the inherent corruption of the feudal era. The bad of ninjas has a rather scrappy quality, not quite as sleek as the Iga of previous films while also a little naive. Shooting more like a standard jidaigeki, Ikehiro uses relatively few ninja tricks generally sticking to smoke and blow tarts with a few shrunken battles. Nevertheless, the violence itself is surprisingly visceral beginning with unexpected severing of an arm and leading to a man getting stabbed in both eyes. Then again, the film ends in the characteristically upbeat way which has become somewhat familiar only this time Kojiro runs back towards romantic destiny now freed of his mission of vengeance and the oppressive ninja code.

These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.