Is it a good idea to advertise your haunted a house attraction by making a movie in which people get trapped inside haunted house? Whether or not Shock Labyrinth (戦慄迷宮3D, Senritsu Meikyu 3D) had the desired effect of luring more guests to Fuji-Q Highland’s Labyrinth of Horrors is probably lost to time, though Takashi Shimizu’s 2009 ghostly drama is also a strange curio produced during the short-lived resurgence of 3D in the late 2000s though this, of course, also means that it was shot with the flattened aesthetics of early digital technology.

In essence, the film casts traumatic memory as a haunted space of the brain in which the protagonist is plagued by the disappearance of a friend inside the fairground attraction he and his friends snuck into as children. Yuki (Misako Renbutsu) makes a sudden reappearance when Ken returns to his hometown. She claims to have been trapped for a very long time, but has grown along with the others and her clothes have somehow grown with her so that she has the appearance of a ghostly adult woman who behaves like a child. When the gang try to take her to a hospital, they unwittingly end up back at the fake one from the fairground attraction and are forced to face their unresolved guilt and trauma.

Indeed, it seems most of them had completely forgotten about Yuki and got on with their lives. Gradually recovering his memories, Ken (Yuya Yagira) blames himself for Yuki’s death while Motoki, who denies all responsibility, becomes convinced that Yuki’s vengeful ghost brought them back here deliberately to get her revenge for them leaving her there. It’s true enough that the others all ran off after becoming frightened without thinking about Yuki and made no attempt to rescue her, and that they went into the haunted house while knowing they weren’t supposed to, but, on the other hand, they were all children and acted in ways children do. Then again, there were already ructions and petty jealousies dividing the group as it appears Ken was the more popular member liked by both Rin and Yuki, provoking a series of jealousies and resentment from Motoki who declares that he’s not going to bother save Rin because she didn’t love him anyway. Ironically, she’s just told Ken that Motoki was the only one who really cared about her when Ken only helped her out of a sense of pity because she is blind. Miyu, Yuki’s younger sister, had also been jealous of her for being so “perfect and nice” when she was always the “bad” one who got into trouble.

This shock labyrinth is really the space of repressed memories that Ken talks about. What it seems Yuki wants, like many similar ghosts, is company and to trap her friends with her within this space, or at least as much as she’s a manifestation of Ken’s buried guilt, to prevent him from ever really forgetting her and going on with his life. Ken and the others desperately search for an exit, but are ultimately unable to overcome their traumatic memories. Yuki comes for them as soon as they remember what they did to her, as if they were really being stalked by their own repressed guilt and shame. Still never having dealt with the death of his mother, Ken dreams of her telling him not to go into the haunted hospital or Yuki will him as if she wanted to protect him from this harmful memory though repressing it is evidently as damaging as confronting the truth of the past.

The detectives meanwhile adopt the more rational view that Ken is responsible for everything having taken revenge on his friends for abandoning Yuki when they were children. Perhaps this is all really going on in the shock corridors of Ken’s mind as his traumatic memories have begun to leak out and distort his sense of reality. Then again, perhaps Yuki has found a way to come back for deadly game of hide and seek to keep her occupied in the between space of the fake haunted hospital with its creepy, decomposing mannequins and the unexpectedly gruesome plush rabbit backpack the young Yuki was forever carrying around and refused to let others touch. Either way, it seems Yuki will not let them go but will always be there in the dark corners of their minds to remind them what they’ve done.

Trailer (English subtitles)

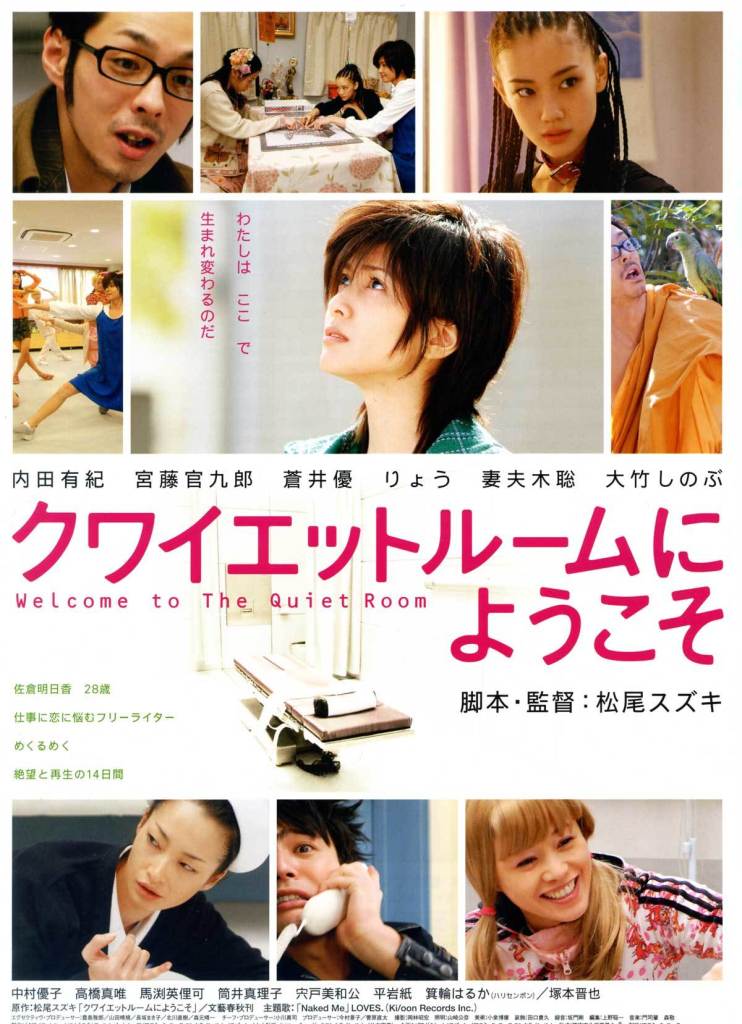

Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden.

Everyone has those little moments in life where you think “how did I get here?”, but thankfully most of them do not occur strapped to a table in an entirely white, windowless room. This is, indeed, where the heroine of Suzuki Matsuo’s adaptation of his own novel Welcome to the Quiet Room (クワイエットルームにようこそ, Quiet Room ni Yokoso) finds herself after a series of events she can’t remember but which seem to have involved pills and booze. A much needed wake up call, Asuka’s spell in the Quiet Room provides a long overdue opportunity to slow down and take a long hard look at herself but self knowledge can be a heavy burden.

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by

When it comes to tragic romances, no one does them better than Japan. Adapted from a best selling novel by Takuji Ichikawa, Be With You (いま、会いにゆきます, Ima, ai ni Yukimasu) is very much part of the “Jun-ai” or “pure love” boom kickstarted by  Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.

Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.