Is it truly possible to retreat from the world and live a pure life free of Earthly desires? Perhaps not, at least not entirely as the monks of King Hu’s joyously comic wuxia Raining in the Mountain (空山靈雨, Kōng Shān Líng Yǔ) later discover in attempting to cure the corruption already eating through their ranks. The old abbot is ill and mindful that his time is short, recruits a series of advisors to help him pick a successor to steer the monastery in his absence yet whether he too is plotting or not there is intrigue at play and not everyone’s motives are strictly spiritual.

The film opens with Hu’s trademark immersion in the beauty of nature as three pilgrims approach a mountain temple yet there’s something almost suspicious in their manner as they’re met by the abbot’s reliable righthand man, Hui Ssu (Paul Chun Pui). Esquire Wen (Sun Yueh), a wealthy merchant and frequent donor, introduces the woman with him as his concubine, the man obviously a servant given that he’s carrying their pack. Wen has, however, an ulterior motive in that he’s come with the intention of stealing a unique scroll featuring the Mahayana Sutra in the hand of Xuanzang/Tripitaka of Journey to the West fame. The woman is no concubine but a famous thief, White Fox (Hsu Feng), who wastes no time at all before changing into her best sneaking clothes and reuniting with the servant, her minion Chin Suo (Wu Ming-Tsai), to try and break into the sutra room.

They are not however alone in their endeavours. The abbot has also invited local police chief General Wang (Tien Feng) and his underling Chang Cheng (Chen Hui-Lou) who nominally favour monk Hui Tung (Shih Chun) for the position of abbot but are also there largely with the intention of getting their hands on the scroll which Hui Tung has pledged to give them if he wins. Likewise, though it seems Esquire Wen had forgotten to brief White Fox, rival candidate Hui Wen (Lu Chan) is also in league with them. Just as it looks as if this duality is about to implode, the introduction of a third party, former convict Chiu Ming (Tung Lin) who claims he was framed by Chang Cheng because his family refused to sell him a precious scroll, creates additional uncertainty in the race for succession.

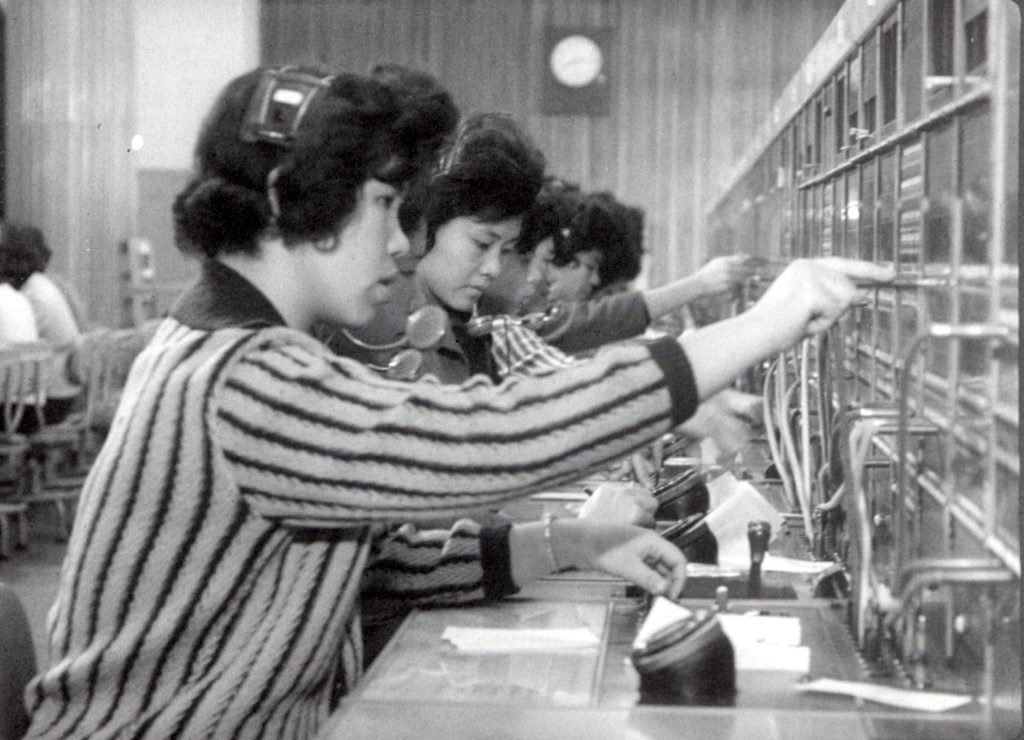

Secluded in the mountains, the temple ought to be a refuge of enlightenment free from spiritual corruption in its isolation from Earthly desires. Even so, we’re told that the most holy man is the third advisor, Wu Wai (Wu Chia-Hsiang), a Buddhist lay preacher who arrives with a massive entourage of colourfully dressed handmaidens and is said to be “immune to sensual pleasures”. He favours no particular candidate, but acts as a spiritual sounding board at the right hand of the abbot who may or may not be aware that his other two advisors have ulterior motives, or that corruption is already rife in the monastery. Aside from the power-hungry machinations of Hui Wen and Hui Tung, who is so desperate for the position he later consents to murder on temple grounds, many of the younger monks have been bribing a pedlar to smuggle in meat and wine for them, literally passing it over the fence, and not even paying him properly. They are also tested perhaps deliberately by Wu Wai who has his handmaidens frolic in the water where the monks are supposed to be meditating, many of them unable to maintain concentration.

Yet these are only partial incursions, the monastery is not entirely isolated from the wider society by virtue of its financial dependency. Wu Wai who lives on the outside seems to be fantastically wealthy (still it seems clinging on to material desires), yet the temple is dependent on donations from men like Esquire Wen or else on alms giving. On her arrival, White Fox disdainfully rejects the meal she’s offered and describes the place as a dump, her complaints apparently not unfounded as a ruse to raise rebellion by staging a protest about the the low quality of the catering strikes a genuine note of discord with the monks. The solution posited by the new abbot, opting for austerity rather than opulence, is to tell the young monks they’ve had it too easy and now it’s time they shift for themselves by aiming to become self-sufficient growing their own veg (and thereby lessening their contact with worldly corruption).

In any case, they cannot purify the temple while the temptation of the scroll exists. “Priceless” to General Wang and Esquire Wen, to the abbot and interestingly to White Fox, the scroll is “worthless” merely a raggedy bit of old paper with no intrinsic value. Yet hoping to raise revenue, the new abbot is advised to borrow on its collateral by the duplicitous Esquire Wen and thereby is forced to accept its “worth” in the secular world perhaps only then realising that if the temple wishes to finalise its divorce the scroll has to go. Essentially a morality tale, Hu hints at the absurdity of these petty corruptions in the cartoonish, farcical shenanigans of the rival thieves as they dance around each other silently fighting over a “worthless” scroll the camera following them with a wry eye while the constant drumming of the background score lends a note of ever present tension. Almost everyone, it seems, is redeemable for the path to enlightenment should be available to all though those who choose not to follow it may find the way of corruption leads to only one destination.

Raining in the Mountain streams in the US until Sept. 28 as part of the 13th Season of Asian Pop-Up Cinema.

Restoration trailer (English subtitles)