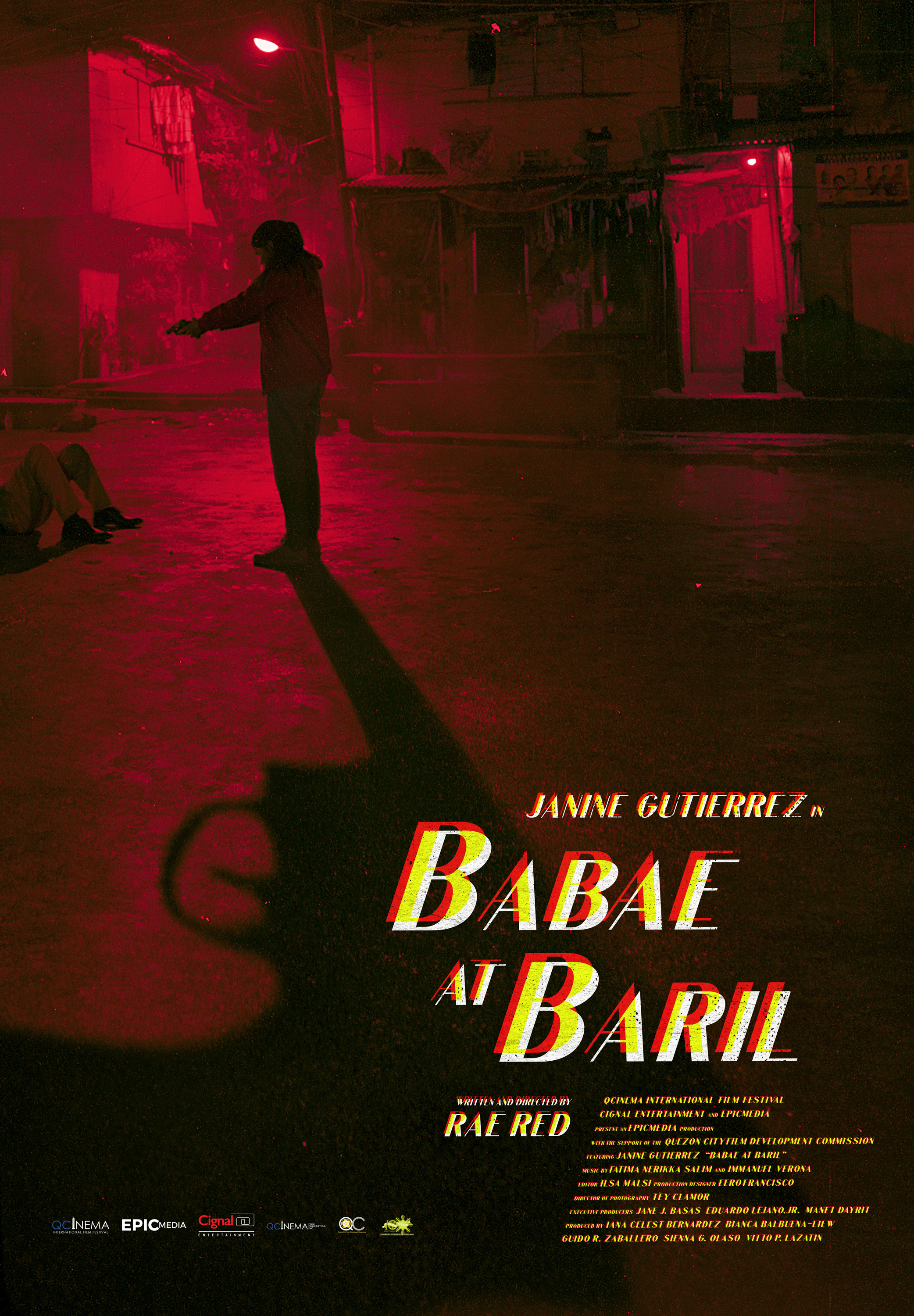

“Everything is personal” according to one extremely oppressed young man in Rae Red’s neo noir voyage through the legacies of authoritarian violence, The Girl and the Gun (Babae at Baril). Drawing a direct line from Marcos-era oppression to Duterte’s Philippines and the war on drugs, Red’s debut solo feature is an irony-fuelled inquisition of the modern society equally ruled by fear and desperation in which many feel violence is the only recourse against their sense of despair only to discover that violence breeds only more of the same in a nihilistic spiral of hopeless impotence.

The never named heroine (Janine Gutierrez) is a meek and mild young woman who works in a department store where women, in particular, are expected to be prim and proper. The girl, however, is forever pulled up about the ladder in her tights, seemingly her only pair and as we’ll see she cannot afford to buy a replacement nor will one be provided for her by her employers who pat down employees as they leave the store each evening to ensure they haven’t stolen anything. Despite this however she believes she works hard and is under-appreciated, her sense of disappointment palpable as she witnesses another young woman be named employee of the month. Her colleagues view her as aloof because she is always the last to leave the building and never joins them for drinks, little knowing that it’s not her shyness that keeps her away but shame in her poverty. She has a long and arduous journey home to the poor part of town where she shares a room with another young woman, unable even to make her rent because she sends most of what she earns to the mother she apparently feels unable to return to. For all these reasons, she finds herself alone with a predatory colleague (Felix Roco) who rapes her, sheepishly apologises, and then returns with more threatening violence to advise her to keep her mouth shut.

The evening before she’d heard a gun shot, left her apartment to investigate and seen a man run away, noticing an abandoned pistol with a heart on the barrel discarded in a rubbish bin. After the rape, she picks it up, immediately pointing it directly at the abusive boyfriend of her roommate. The gun gives her a sense of empowerment that counters the trauma of her victimisation. She is already beyond caring and can now say all the things she’s ever wanted to say to the men who treat her with such utter contempt, taking a flirty customer to task for his inappropriate behaviour with his young daughter sitting right next to him, and eventually giving her boss a piece of her mind when he finally fires her over something as petty as a barely visible uniform infraction.

The girl had not usually been the type to complain, both her sleazy landlord and priggish boss keen to tell her that there are plenty of people waiting to take her place as if she should be grateful that her awful life is still not more awful. She and her friend dream of escaping the city, going home, or at least far away to a place where they could live a better life. Jun Jun (Elijah Canlas) the teenage drug dealer from the news reports dreams of something similar, lamenting most of all that he had homework due before he became the subject of a manhunt with which he’d struggled. He wonders how he might have done. His friend gives him all his savings which he’d been collecting for his own escape, hoping to return to his mother with his younger sister in tow in order to save her from a father he at least fears is abusive.

Tracking through the history of the gun before it found its way into the hands of the girl, Red takes us back to the authoritarian violence of the Marcos regime as a nervous policeman assassinates “activists” in place of the current “drug dealers”, his son eventually picking up his gun a “policeman” like his father but filled with resentment towards inescapability of his fate. The gun passes from hand to hand, a child sticking the little heart sticker on it, creating only more chaos wherever it goes. It gives the girl the courage she thought she lacked to seize her agency, to talk back, to be “unladylike” in insisting on her equality in the face of the countless men who ignore, cat call, and abuse her. But the gun itself is not enough, her quest for violent vengeance hollow and unfulfilling, the only real liberation coming as she decides to abandon it in a final act of catharsis that breaks the cycle of violence and oppression which had trapped each of the gun’s owners. As a boy had said, it’s all personal. You might think it’s nothing to do with you, but you can’t escape the oppressions of the world in which you live be they poverty, misogyny, or authoritarianism.

Largely taking place at night, Red bathes her city in the tones of neo noir, a land of shadows among neon, a shining cityscape of high rise buildings the like of which neither the girl or the street kids are ever likely to enter. Making fantastic use of music from the noirish jazz to the nostalgic pop of the oppressive ‘80s she fully embraces the pulpy exploitation of the material but always maintains a sense of playful irony, never forgetting the full import of her sometimes grim satire of life on the margins of Duterte’s Philippines as her variously oppressed protagonists seek freedom in violence but find only more constraint in the depths of nihilistic despair.

The Girl and the Gun streamed as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)