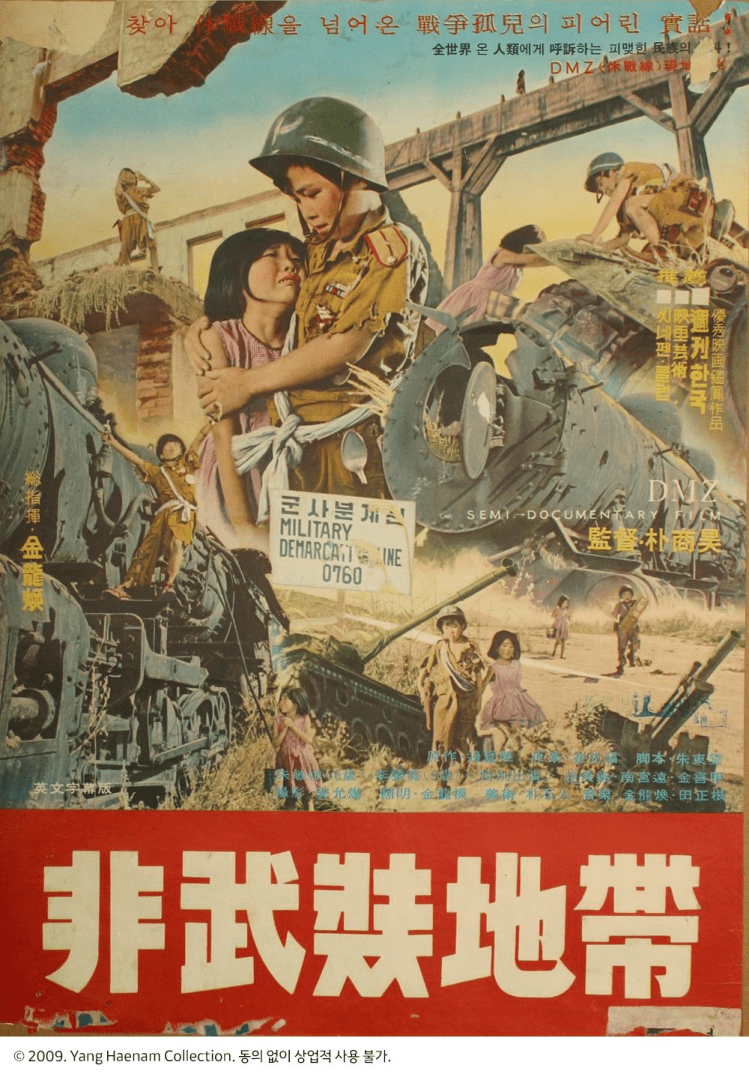

Talking about the “reunification” of Korea could be a risky business in the increasingly censorious 1960s. Directors had been jailed for less, and the anti-Communism drama was fast becoming a staple genre in the rapidly expanding film industry. Director Park Sang-ho had been at the forefront of Korea’s burgeoning International cinematic success when his 1963 film A Happy Businesswoman had been selected for the Tokyo film festival. Whilst there to present the film (which picked up a best actress award for Do Keum-bong), Park was met with consternation by foreign delegates who assumed he was Japanese and could show them around Tokyo. On learning he was Korean all they wanted to know about was the Demilitarised Zone and the village that was trapped inside it – Panmunjeom. Park had no answers for them. He’d never been to Panmunjeom and knew nothing about it, but he was surprised and concerned that an obscure little village and an ongoing political dispute had come to dominate the thinking surrounding his country with Panmunjeom emerging as a grim tourist destination for those interested in experiencing the “thrill” of life in a dormant war zone.

Talking about the “reunification” of Korea could be a risky business in the increasingly censorious 1960s. Directors had been jailed for less, and the anti-Communism drama was fast becoming a staple genre in the rapidly expanding film industry. Director Park Sang-ho had been at the forefront of Korea’s burgeoning International cinematic success when his 1963 film A Happy Businesswoman had been selected for the Tokyo film festival. Whilst there to present the film (which picked up a best actress award for Do Keum-bong), Park was met with consternation by foreign delegates who assumed he was Japanese and could show them around Tokyo. On learning he was Korean all they wanted to know about was the Demilitarised Zone and the village that was trapped inside it – Panmunjeom. Park had no answers for them. He’d never been to Panmunjeom and knew nothing about it, but he was surprised and concerned that an obscure little village and an ongoing political dispute had come to dominate the thinking surrounding his country with Panmunjeom emerging as a grim tourist destination for those interested in experiencing the “thrill” of life in a dormant war zone.

On return to Korea he knew he had to make a film about the DMZ, but the subject was a difficult, perhaps taboo one which had to be approached carefully. Park’s first cut which was released in theatres ran to 90 minutes and conformed more obviously to the standard commercial cinema of the time. In a radical move, the director then decided to re-edit it with the intention of submitting to foreign film festivals. Cutting most of the scenes with well known actors, Park retained only the stock footage which bookends the film (apparently enough to qualify the remainder as a “documentary” rather than narrative feature), and the central drama focussing on two small children desperately wandering the ruined landscape alone in search of their mothers.

The younger of the two, Yong-ha (Ju Min-a) – a five year old girl, falls into a lake and is rescued by an 8-year-old boy (Lee Yeong-gwan) she originally mistakes for a grown man because of the ragged military uniform and soldier’s helmet he is wearing. The unnamed little boy tells Yong-ha he had a little sister with her name, and there are enough coincidences in their back stories to make one wonder if they really might be related, but in any case the boy “becomes” Yong-ha’s big brother and agrees to protect her while they each look for their long lost mothers.

As the pair are only children, they do not really know that they’re in the “DMZ” or what the DMZ is, they only know they are alone and surrounded by danger. Skeletons and decomposing bodies are a frequent sight, as are abandoned tanks, overturned trucks, broken trains, and rusty equipment. There are no other people, and nature has begun to reclaim the land – wild dogs and foxes are potential perils, while Yong-ha later finds herself separated from her brother after chasing a cute rabbit into a woodland grove and then being unable to find her way back.

The allegory becomes clearer as the children engage in absurd games exposing the arbitrary and destructive nature of the division itself. Walking up to the line, the boy gleefully jumps over to show Yong-ha how meaningless it is. Yong-ha, enjoying the game, thinks “division” seems fun and they should try it out for themselves. Her brother agrees, marking his territory and then insisting that they turn their backs on each other and refuse to speak. He keeps this up for quite a while until Yong-ha becomes distressed, at which point he jumps up and smashes the makeshift division marker to pieces so he can once again embrace his sister.

Nevertheless the anticommunist sentiments are present in the form of a cruel and callous North Korean spy who tries to kidnap the children and take them away with him. To add to the spirit of adventure, the boy sings a nationalist song which honours those who have given their lives to “liberate” the country from “oppression”, while a propaganda broadcast tries to do something similar whilst the children are playing division by offering a message of solidarity to those in the North who might like to come South. Dangerous as the situation is, the children’s innocent naivety eventually leads to a small diplomatic incident when they unwittingly pick up a landmine to use as a firestone but are frightened away by the approach of soldiers just before it explodes, leading both sides to claim the act as one of provocation by the other.

Park takes the dangerous step of shooting directly within the real DMZ with all of its eeriness as a place abandoned by humanity and filled with man made dangers. The children attempt to survive in it alone – foraging for food, using the wood from crosses put up as grave markers to start fires, and looking after each other in the absence of adults. They play when they can, swimming, pretending to commandeer tanks and steal trains, pilfering left behind supplies and always talking about their families and how best to find them. The theatrical version, as was expected at the time, apparently has a more positive ending but Park refuses to soft-pedal the disproportionate suffering experienced by children in time of war, even whilst adding a pointed statement to the end advancing the cause of Korean brotherhood and calling for an end to the unfair and arbitrary separation of a people which feels itself to be of one blood. Unusual for the time but ending on a note of hope (if however bleak), DMZ is part anti-communist propaganda, part unification treatise, and most of all the story of two unlucky orphans created by a war and a diplomatic stalemate who find themselves alone in no-man’s land with no safe refuge in sight.

The DMZ (비무장지대 / 非武裝地帶, Bi-mu-jang Ji-dae) is available on DVD with English subtitles courtesy of the Korean Film Archive. The set also includes an English subtitled documentary about the career of director Park Sang-ho as well as a 32-page bilingual booklet. Not currently available to stream online.

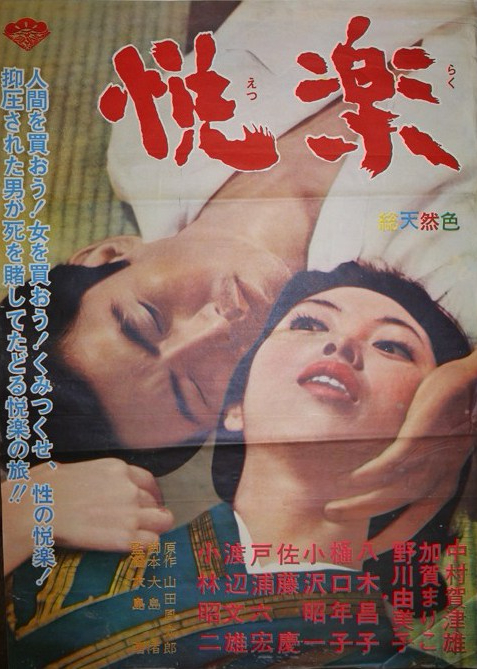

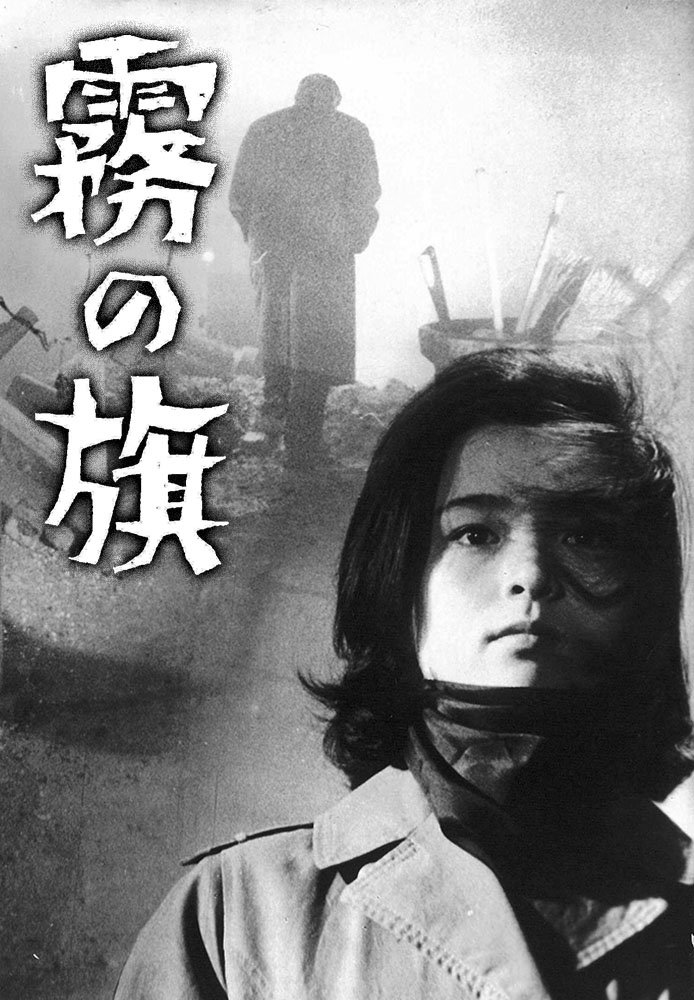

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger. Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt.

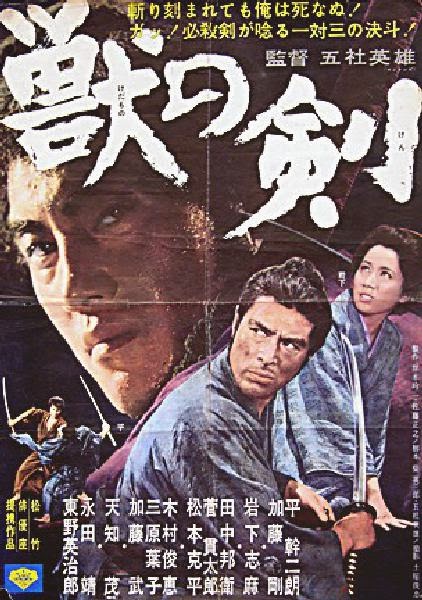

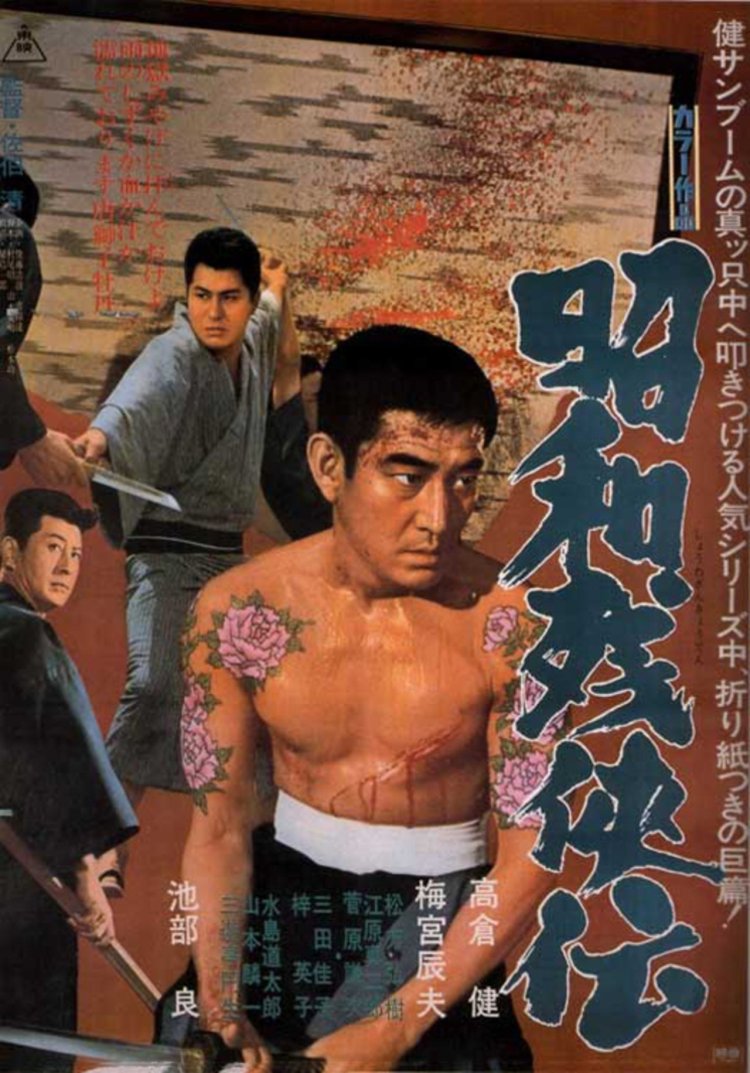

Shiro Toyoda, despite being among the most successful directors of Japan’s golden age, is also among the most neglected when it comes to overseas exposure. Best known for literary adaptations, Toyoda’s laid back lensing and elegant restraint have perhaps attracted less attention than some of his flashier contemporaries but he was often at his best in allowing his material to take centre stage. Though his trademark style might not necessarily lend itself well to horror, Toyoda had made other successful forays into the genre before being tasked with directing yet another take on the classic ghost story Yotsuya Kaidan (四谷怪談) but, hampered by poor production values and an overly simplistic script, Toyoda never succeeds in capturing the deep-seated dread which defines the tale of maddening ambition followed by ruinous guilt. Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family?

Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family?