A naive girl from the mountains finds herself chasing consumerist success and urban independence only to encounter further exploitation before eventually transcending her subjugation and returning to the source of her trauma in an ironic picaresque from the characteristically anarchic Seijun Suzuki. Adapted from a novel from Toko Kon whose book also provided the source material for The Incorrigible, Carmen from Kawachi (河内カルメン, Kawachi no Carmen) loosely adapts Bizet’s classic opera but ironically discovers a much positive outcome for its relentlessly plucky heroine.

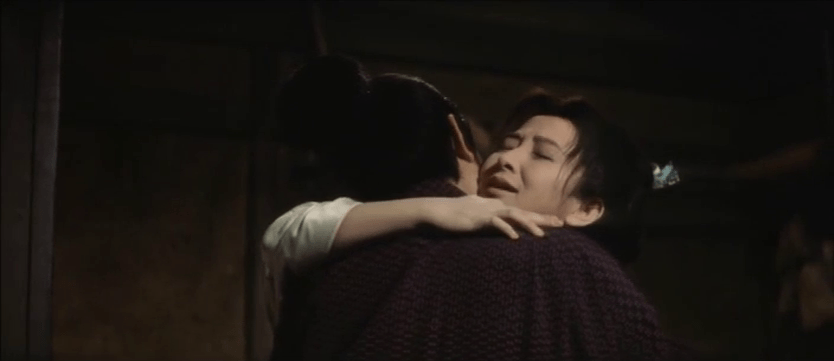

In Kawachi, meanwhile, a rural mountain backwater near Osaka, Tsuyuko (Yumiko Nogawa) is a rather innocent young woman with a crush on the son of the local factory owner, Bon (Koji Wada), who seems to like her too but is equally diffident if presumably mindful of the class difference which makes a relationship between them unlikely to succeed. Tsuyuko’s friend tells her of a girl from school who now works in a cabaret bar in the city and has all the mod cons in her fancy apartment including an electric fridge, washing, machine, and double bed but Tsuyuko doesn’t seem to be too impressed. However, when a pair of local reprobates overhear her romantic conversation with Bon, they begin to feel resentful and decide to rape her. As they approach Tsuyuko, they are seemingly joined by a small crowd of men from the local area each chasing after her. On her return home, she simply bursts into tears but is greeted by an even worse sight, catching her mother (Chikako Miyagi) in a passionate embrace with a lecherous monk whose disgusting fisheye face continues to haunt her, a spectre both of a world of patriarchal exploitation and her own prudishness which is also coloured by the trauma of her rape.

Tsuyuko is indeed followed around by various men who are all in their way disappointing in their desire to possess her body. “When a woman sleeps with a man just one time, the man thinks she belongs to him”, her school friend explains after she begins working in the bar in Osaka thinking that as her honour’s already lost she might as well try cabaret. Yet there is a kind of power play involved in the hostess life, the men all running after Tsuyuko who only has to stand still and can in fact manipulate them in turn. Then again, as soon as she starts work she ends up having too much to drink and sleeping with a sad sack salaryman who lied that he was also from Kawachi in an attempt to win her sympathy. Like many in the bar he thinks of her as a bumpkin still smelling of mountain soil and is disappointed she’s not a virgin but then becomes obsessed with her to the point of ruination. Kanzo (Asao Sano) embezzles a humiliatingly small amount of money from the financial company where he works and is fired, hanging out in the rain outside the bar just to catch a glimpse of Tsuyuko. Tsuyuko isn’t interested in him but ends up feeling bad about her role in his downfall and letting him move into her apartment where he becomes something like her wife, taking care of all the domestic arrangements and even ironing her smalls.

For all that, Kanzo’s not that bad. He’s a sweet, if pathetic, guy who takes her sudden announcement that she’s moving on with good grace explaining rather sadly that these have been the happiest days of his life but he never expected them to last. Rather than a jealous lover, he willingly lets her go even agreeing to put on a show of anger so she won’t feel bad about abandoning him. In many mays, Kanzo is one of the best men she’s going to meet, save perhaps wealthy artist Seiji (Tamio Kawaji) who seem to have no romantic interest in her but becomes a valuable friend and confident. Then again, it’s not just men. After taking a job as a model to try and move on from the cabaret life, she’s sexually harassed by a predatory lesbian boss who takes her in as a maid and then tries to force her attentions on her, possibly lacking the language for seduction in this less enlightened age. When Seiji had tried to explain that her boss is a lesbian, Tsuyuko had simply laughed and been unable to believe such a thing could be true.

Suzuki pulls back from the fashion entrepreneur’s home to frame it as a dollhouse stage set, Tsuyuko now merely another plaything but also herself playing a role in the newly aspirant society. She does so again when Seiji gets her the gig as a mistress for a loanshark who sets her up in a fancy apartment but only asks her to wander around in the nude apparently interested in little other than voyeurism. Tsuyuko only agrees because she continues to chase the dream of pure love with Bon whom she has reencountered by chance. He is now brought low as his factory has gone bust and he’s broke which dissolves the class difference between them. But Bon is also chasing an elusive dream, in his case of success back in Kawachi by building an onsen at the site of a mysterious waterfall no one has been able to find for decades. Just as Tsuyuko is forced to prostitute herself for Bon, Bon prostitutes himself for his dream in that as she discovers he is her partner in a porn shoot directed by the sleazy loanshark who quite clearly also gets off on the romantic drama in play and the destruction of the “pure” love between Bon and Tsuyuko.

Part of Tsuyuko’s disillusionment had been caused by the discovery that not only was her mother sleeping with the creepy priest but that she was doing it for money and her father knew. Her troubles have largely be precipitated by male failure, firstly her father’s in his inability to support his family, secondly in the fragile masculinity of the local boys who assaulted her, and then finally in the weakness of Bon who chose his fleeting dream of local success over his love for her. Having inherited the loanshark’s riches after he is randomly killed in a plane crash, Tsuyuko discovers she no longer wants them and tries to free her mother from male exploitation by giving her money in part for a decent funeral for her father. Only then does she learn that her mother has already substituted her younger sister Senko (Ruriko Ito), forcing her to sleep with the priest and blaming Tsuyuko for it for having run away.

Tsuyuko takes dark and destructive action to rid herself of the troublesome priest as if exorcising the roots of her trauma, no longer afraid of men or of sex but firmly in charge of herself and her body. Her mother is not, however, particularly happy to be emancipated if ironically expressing the same sentiment in that she need have no fear of loneliness or penury for she can always find company if she desires it. Unlike Carmen, Tsuyuko is not undone by toxic masculinity and frustrated male pride but eventually transcends them even if as her mother says she may never be free of the priest’s “dark magic” while she takes to the streets of Tokyo with a rose in her teeth looking, if not quite perhaps for love, then at least satisfaction. Brimming with the joie de vivre and anarchy that would later make him famous from the raucous club scenes to the ironic framing of the porno shoot and dramatic freeze frames as Tsuyuko finally loses her faith in men, Suzuki’s Carmen allows its pure hearted heroine not only to triumph over the forces that oppress her be they men or merely consumerism but to subvert them to her advantage.

Carmen from Kawachi screens at Japan Society New York on Feb. 10 as part of the Seijun Suzuki Centennial.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Images: (c)1966 Nikkatsu Corporation