Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness.

Despite the potential raciness of the title, The Liar and his Lover (カノジョは嘘を愛しすぎてる, Kanojo wa Uso wo Aishisugiteru) is another innocent tale of youthful romance adapted from a shojo manga by Kotomi Aoki. As is customary in the genre, the heroine is cute yet earnest, emotionally honest and fiercely clear cut whereas the hero is a broken hearted artist much in the need of the love of a good woman. Innocent and chaste as it all is, Liar also imports the worst aspects of shojo in its unseemly age gap romance between a 25 year old musician and the 16 year old high school girl he picks up on a whim and then apparently falls for precisely because of her uncomplicated goodness.

Aki (Takeru Satoh) introduces himself through a film noir-style voice over in which he details his ongoing malaise. Now a ghost member of the band Crude Play, Aki feels conflicted over his artistic legacy as his carefully crafted tunes are repurposed as disposable idol pop and performed by the friends who were once his high school bandmates. His idol girlfriend, Mari (Saki Aibu), has also been seeing the band’s manager in an effort to get ahead leaving Aki feeling betrayed and devoid of purpose.

Soon after, Aki runs into grocer’s daughter Riko (Sakurako Ohara) who is captivated by the song he’s been humming whilst staring aimlessly out to sea. Aki, feeling mischievous, picks Riko up on a whim. He goes to great pains to remind us that he had no real feelings for her and was only in it for the kicks but a later meeting sets the pair off on a complicated romance.

Aki becomes the “liar” of the title when he gives Riko a false name – Shinya, the name of the bassist who has replaced him in his own band. Despite the supposed purity of music as a means of communication, it is, in many ways, another lie. When Aki and his bandmates were offered a contract straight after high school they were overjoyed but it was short lived. Listening to their demo tape, Aki spots the problem right away – it’s not them playing, they’ve been replaced by polished studio session musicians. Saddened, Aki quits the band and is replaced by a ringer but continues to write songs both for Crude Play and other artists while the band’s manager gets the credit.

Music conveys and complicates the romance as it brings the two together but also threatens to keep them apart. Riko, a Crude Play fan, does not know Aki’s true identity and is disappointed when he says he hates girls who sing because she herself is in a high school band. Sure enough, the band get scouted by odious producer Takagi (Takashi Sorimachi) and handed to the villainous Shinya (Masataka Kubota) who threatens to do the same thing to them as they did to Crude Play. Riko, like Aki, is a musical purist but also wants to make her rock star dreams come true.

Like many a shojo heroine, Riko is convinced only she sees the “real” Aki, pushing past his angry, distant persona to a deeper layer of sensitive vulnerability. This being shojo she is more or less right, as Aki tells us in his voice over detailing just how irritating it seems to be for him that he’s falling for this unusually perceptive young woman. Despite realising that almost everything Aki has told her has been a lie (intentional or otherwise), Riko ignores his duplicity precisely because she thinks she already knows the “real” Aki through the “truth” of his music.

Takagi, the band’s unscrupulous manager, prattles on about music not mattering if it doesn’t sell, avowing that it’s all a matter or marketing anyway. Aki’s central concern is the misuse of his artistic legacy, that his art form has been stripped of its meaning and repackaged for mass market consumption. The band is “fake”, a manufactured image based on the ruins of the truth. Aki believes himself to be the same – an empty vessel, devoid of meaning or purpose. His love of music is only reawakened by Riko’s innocent enthusiasm and her surprising promise of “protection”.

The conflict is one of essential truth betrayed by music in all senses of the word as it is used and misused by the various forces in play. Unlike most shojo adaptations, Aki leads the way with Riko a vaguer figure ready to absorb the projected personalities of the target audience but the central dynamic is still one of goodhearted girl and broody boy. The unseemly age gap issue is entirely ignored, as the troubling undercurrent of Riko’s most attractive quality being her all encompassing pureness, undermining the otherwise charming, wistful comedy of the innocent musical romance.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Schoolgirl Complex is a popular photo book featuring the work of Yuki Aoyama and does indeed focus on that most most Japanese of fixations – the school girl and her iconic uniform. Aoyama’s book presents itself as taking the POV of a teenage boy, gazing longly from a position of total innocence at the unattainable female figures who, in the book, are entirely faceless. Given a more concrete narrative, this filmic adaptation (スクールガール コンプレックス 放送部篇, Schoolgirl Complex Housoubu-hen) directed by Yuichi Onuma takes a slightly different tack in dispensing with high school boys altogether for a tale of self discovery and sexual confusion set in an all girls school in which almost everyone has a crush on someone, but sadly finds only adolescent suffering as so eloquently described by Osamu Dazai whose Schoolgirl informs much of the narrative.

Schoolgirl Complex is a popular photo book featuring the work of Yuki Aoyama and does indeed focus on that most most Japanese of fixations – the school girl and her iconic uniform. Aoyama’s book presents itself as taking the POV of a teenage boy, gazing longly from a position of total innocence at the unattainable female figures who, in the book, are entirely faceless. Given a more concrete narrative, this filmic adaptation (スクールガール コンプレックス 放送部篇, Schoolgirl Complex Housoubu-hen) directed by Yuichi Onuma takes a slightly different tack in dispensing with high school boys altogether for a tale of self discovery and sexual confusion set in an all girls school in which almost everyone has a crush on someone, but sadly finds only adolescent suffering as so eloquently described by Osamu Dazai whose Schoolgirl informs much of the narrative. When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives.

When everything goes wrong you go home, but Yuriko, the protagonist of Yuki Tanada’s adaptation of Yuki Ibuki’s novel might feel justified in wondering if she’s made a series of huge mistakes considering the strange situation she now finds herself in. Far from the schmaltzy cooking movie the title might suggest, Mourning Recipe (四十九日のレシピ, Shijuukunichi no Recipe) is a trail of breadcrumbs left by the recently deceased family matriarch, still thinking of others before herself as she tries to help everyone move on after she is no longer there to guide them. Approaching the often difficult circumstances with her characteristic warmth and compassion, Tanada takes what could have become a trite treatise on the healing power of grief into a nuanced character study as each of the left behind now has to seek their own path in deciding how to live the rest of their lives. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. Junichi Inoue is better known as a screenwriter and frequent collaborator of avant-garde/pink film provocateur Koji Wakamatsu. A Woman and a War (戦争と一人の女, Senso to Hitori no Onna) marks his first time in the director’s chair and finds him working with someone else’s script but staying firmly within the pink genre. Adapted from a contemporary novel by Ango Sakaguchi published in 1946, A Woman and a War is an intense look at domestic female suffering during a time generalised chaos.

Junichi Inoue is better known as a screenwriter and frequent collaborator of avant-garde/pink film provocateur Koji Wakamatsu. A Woman and a War (戦争と一人の女, Senso to Hitori no Onna) marks his first time in the director’s chair and finds him working with someone else’s script but staying firmly within the pink genre. Adapted from a contemporary novel by Ango Sakaguchi published in 1946, A Woman and a War is an intense look at domestic female suffering during a time generalised chaos. How many times were you told as a child, someday you will understand this? There are so many things you don’t see until it’s too late, and children being as they are, are almost programmed to see things from a self directed tunnel vision. Such is the case for Mugiko – a young woman with dreams of becoming an anime voice actress who is suddenly reunited with her estranged mother of whom she has almost no memory.

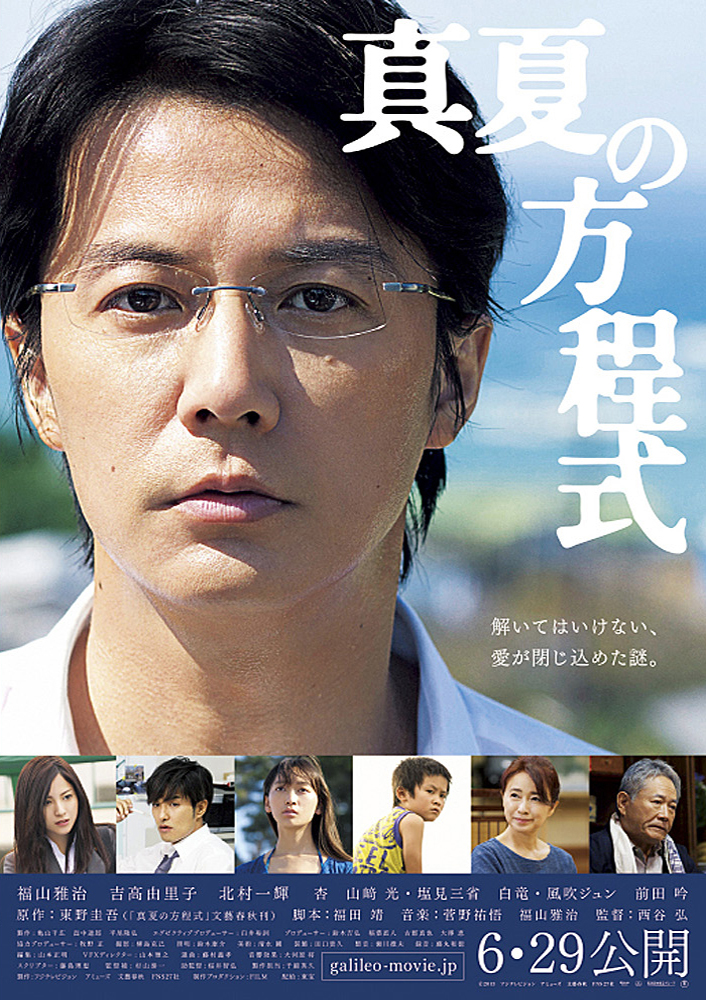

How many times were you told as a child, someday you will understand this? There are so many things you don’t see until it’s too late, and children being as they are, are almost programmed to see things from a self directed tunnel vision. Such is the case for Mugiko – a young woman with dreams of becoming an anime voice actress who is suddenly reunited with her estranged mother of whom she has almost no memory. Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life. Jellyfish Eyes (めめめのくらげ, Mememe no Kurage) is the feature film debut of the internationally popular Japanese artist, Takashi Murakami. Well known for his cutesy character designs which are as likely to turn up in the world’s best regarded art galleries as they are on a kid’s backpack, Murakami is one of Japan’s most highly regarded art exports. Having unsuccessfully tried to raise interest in the more obvious totally CG animation, Murakami has enlisted the help of gore master Yoshihiro Nishimura for some director’s chair tips in creating a live action/CGI hybrid. Jellyfish Eyes is very definitely a kids’ movie, calling it a “family film” seems unfair when the age cut off is most likely around seven or eight years old but those who meet the (lack of) height requirement are sure to lap it up.

Jellyfish Eyes (めめめのくらげ, Mememe no Kurage) is the feature film debut of the internationally popular Japanese artist, Takashi Murakami. Well known for his cutesy character designs which are as likely to turn up in the world’s best regarded art galleries as they are on a kid’s backpack, Murakami is one of Japan’s most highly regarded art exports. Having unsuccessfully tried to raise interest in the more obvious totally CG animation, Murakami has enlisted the help of gore master Yoshihiro Nishimura for some director’s chair tips in creating a live action/CGI hybrid. Jellyfish Eyes is very definitely a kids’ movie, calling it a “family film” seems unfair when the age cut off is most likely around seven or eight years old but those who meet the (lack of) height requirement are sure to lap it up.