Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything.

Hitoshi One has a history of trying to find the humour in an old fashioned sleazy guy but the hero of his latest film, Scoop!, is an appropriately ‘80s throwback complete with loud shirt, leather jacket, and a mop of curly hair. Inspired by a 1985 TV movie written and directed by Masato Harada, Scoop! is equal parts satire, exposé and tragic character study as it attempts to capture the image of a photographer desperately trying to pretend he cares about nothing whilst caring too much about everything.

Shizuka (Masaharu Fukuyama) is a man out of time. Once the best photojournalist on his paper, he’s ridden the waves of a changing industry and become a high earning freelance paparazzo. Shizuka’s nights are spent in all of the fashionable if occasionally squalid drinking holes of the city in which the elites of the entertainment world attempt to disappear. Sadako (Yo Yoshida), the editor of Scoop! – a once proud publication now a seedy scandal rag, worries about her old friend, his debts, and his legacy. Offering to pay him well above the going rate for anything useable, she saddles him with the latest new recruit – Nobi (Fumi Nikaido), a naive young woman dressing in the bold childhood nostalgia inspired fashion trends of Harajuku. As might be assumed the pair do not hit it off but gradually a kind of closeness develops as Nobi gets into the thrill of the paparazzo chase.

In keeping with his inspiration, One shoots with a very ‘80s aesthetic of a city bathed in neon and moving to the beat of electropop and synth strings. Grainy and grungy, the images are seedy as is the world they capture though this is the Tokyo of the present day, not the bubble era underground. Shizuka claims his major inspiration came from the famous war photographer Robert Capa though now he can’t even remember if he really meant to become a photographer at all. Chasing cheating celebrities and exposing the odd politician for the kind of scandal that sells newspapers is all Shizuka thinks he’s good for, any pretence of journalistic integrity or the “people have a right to know” justification was dropped long ago.

Sadako, however, has more of a business head than her colleagues and is starting to think that Scoop! could be both a serious news outlet and nasty tabloid full of gravure shots and shocking tales of the rich and famous. Getting Shizuka to mentor Nobi is an attempt at killing to two birds with one stone – unite the plucky rookie with the down on his luck veteran for a new kind of reporting, and help Shizuka return to his better days by paying off those massive debts and getting his self esteem back.

Unfortunately Shizuka is his own worst enemy, hanging around with his strange friend Chara-Gen (Lily Franky) who is intermittently helpful but a definite liability. The world of the newspaper is certainly a sexist one – Sadako and Nobi seem to be the only two women around and the banter is distinctly laddish. An ongoing newsroom war leaves Sadako lamenting that the men only think about their careers and promotions rather than the bigger picture while the suggestion that she may win the position of editor has other colleagues bemusedly asking if a woman has ever helmed such a high office. The men ask each other for brothel recommendations and pass sexist comments back and fore amongst themselves with Shizuka trying to out do them all even going so far as to put down the new girl by describing her as “probably a virgin”.

Sadako’s plan begins to work as Shizuka and Nobi become closer, she becoming the kind of reporter who files the story no matter what and he finally agreeing to work on a more serious case. Having spent so long believing everything’s pointless, Shizuka’s reawakening maybe his undoing as a noble desire to help a friend who is so obviously beyond help leads to unexpected tragedy. Nevertheless, the presses keep rolling. A throwback in more ways than one, One’s 80s inspired tale of disillusioned reporters and mass media’s circulation numbers obsessed race to the bottom is all too modern. Unexpectedly melancholy yet often raucously funny, Scoop! is an old fashioned media satire but one with genuine affection for the embattled newsroom as it tries to clean up its act.

Scoop! was screened as part of the Udine Far East Film Festival 2017

Original trailer (no subtitles)

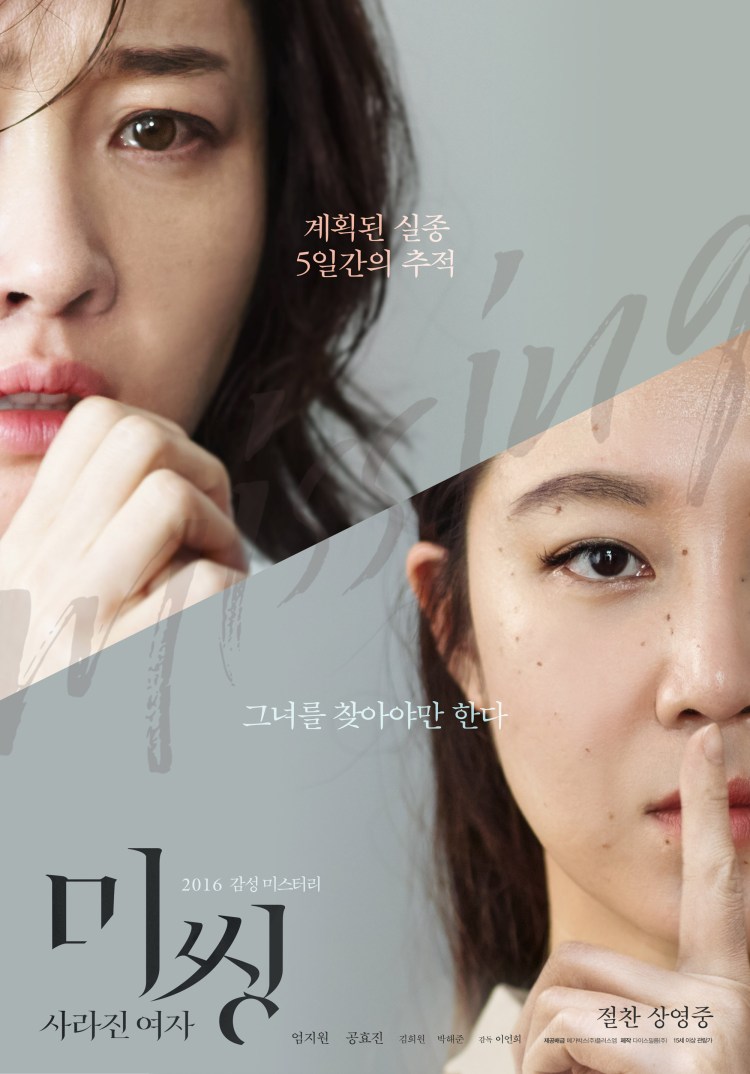

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences.

Since ancient times drama has had a preoccupation with motherhood and a need to point fingers at those who aren’t measuring up to social expectation. E Oni’s Missing plays out like a Caucasian Chalk Circle for our times as a privileged woman finds herself in difficult circumstances only to have her precious daughter swept away from her just as it looked as if she would be lost through a series of social disadvantages. Missing is partly a story of motherhood, but also of women and the various ways they find themselves consistently misused, disbelieved, and betrayed. The two women at the centre of the storm, desperate mother Ji-sun (Uhm Ji-won) and her mysterious Chinese nanny Han-mae (Gong Hyo-jin) are both in their own ways tragic figures caught in one frantic moment as a choice is made on each of their behalves which will have terrible, unforeseen and irreversible consequences. Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by

Review of Zhang Lu’s A Quiet Dream (춘몽, Chun-mong) first published by  Sean Lau Ching-wan and Nicholas Tse are together again after being denied the opportunity to reteam for a sequel to the acclaimed

Sean Lau Ching-wan and Nicholas Tse are together again after being denied the opportunity to reteam for a sequel to the acclaimed  No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice.

No ghosts! That’s one of the big rules when it comes to the Chinese censors, but then these “ghosts” are not quite what they seem and belong to the pre-communist era when the people were far less enlightened than they are now. One of the few directors brave enough to tackle horror in China, Raymond Yip Wai-man goes for the gothic in this Phantom of the Opera inspired tale of love and the supernatural set in bohemian ‘30s Shanghai, Phantom of the Theatre (魔宫魅影, Mó Gōng Mèi Yǐng). As expected, the thrills and chills remain mild as the ghostly threat edges closer to its true role as metaphor in a revenge tale that is in perfect keeping with the melodrama inherent in the genre, but the full force of its tragic inevitability gets lost in the miasma of awkward CGI and theatrical artifice. Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene.

Picking up on the well entrenched penny dreadful trope of the tragic flower seller the Shoujo Tsubaki or “Camellia Girl” became a stock character in the early Showa era rival of the Kamishibai street theatre movement. Like her European equivalent, the Shoujo Tsubaki was typically a lower class innocent who finds herself first thrown into the degrading profession of selling flowers on the street and then cast down even further by being sold to a travelling freakshow revue. This particular version of the story is best known thanks to the infamous 1984 ero-guro manga by Suehiro Maruo, Mr. Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show. Very definitely living up to its name, Maruo’s manga is beautifully drawn evocation of its 1930s counterculture genesis – something which the creator of the book’s anime adaptation took to heart when screening his indie animation. Midori, an indie animation project by Hiroshi Harada, was screened only as part of a wider avant-garde event encompassing a freak show circus and cabaret revue worthy of any ‘30s underground scene.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness.

Children – not always the most tolerant bunch. For every kind and innocent film in which youngsters band together to overcome their differences and head off on a grand world saving mission, there are a fair few in which all of the other kids gang up on the one who doesn’t quite fit in. Given Japan’s generally conformist outlook, this phenomenon is all the more pronounced and you only have to look back to the filmography of famously child friendly director Hiroshi Shimizu to discover a dozen tales of broken hearted children suddenly finding that their friends just won’t play with them anymore. Where A Silent Voice (聲の形, Koe no Katachi) differs is in its gentle acceptance that the bully is also a victim, capable of redemption but requiring both external and internal forgiveness. Yoichi Higashi has had a long and varied career, deliberately rejecting a particular style or home genre which is one reason he’s never become quite as well known internationally as some of his contemporaries. This slightly anonymous quality serves the veteran director well in his adaptation of Arane Inoue’s novel which takes a long hard look at those living lives of quiet desperation in modern Japan. Though sometimes filled with a strange sense of dread, the world of Someone’s Xylophone (だれかの木琴, Dareka no Mokkin) is a gentle and forgiving one in which people are basically good though driven to the brink by loneliness and disconnection.

Yoichi Higashi has had a long and varied career, deliberately rejecting a particular style or home genre which is one reason he’s never become quite as well known internationally as some of his contemporaries. This slightly anonymous quality serves the veteran director well in his adaptation of Arane Inoue’s novel which takes a long hard look at those living lives of quiet desperation in modern Japan. Though sometimes filled with a strange sense of dread, the world of Someone’s Xylophone (だれかの木琴, Dareka no Mokkin) is a gentle and forgiving one in which people are basically good though driven to the brink by loneliness and disconnection. Japan may be famous for its family dramas, but there is a significant substrain of these warm and gentle comedies which sees a prodigal child return to their childhood home either to rediscover some lost aspect of themselves or realise that they no longer belong in the place which raised them. Shuichi Okita’s The Mohican Comes Home (モヒカン故郷に帰る, Mohican Kokyo ni Kaeru) includes an obvious reference in its title to Keisuke Kinoshita’s colourful 1954 escapade

Japan may be famous for its family dramas, but there is a significant substrain of these warm and gentle comedies which sees a prodigal child return to their childhood home either to rediscover some lost aspect of themselves or realise that they no longer belong in the place which raised them. Shuichi Okita’s The Mohican Comes Home (モヒカン故郷に帰る, Mohican Kokyo ni Kaeru) includes an obvious reference in its title to Keisuke Kinoshita’s colourful 1954 escapade  Tharlo producer Wang Xuebo looks north in this rare cinematic showcase for China’s Hui people, a largely Muslim ethnic group concentrated in the rural North West. Using a cast of non-professional actors, Knife in the Clear Water (清水里的刀子, Qingshui Li De Daozi) marries a neorealist aesthetic with a Tarkovskian poetry as a widowed man faces the coming end of his own life largely through his self identification with his faithful bull, about to be sacrificed in the name of dead for the pleasure of the living. Setting religion to one side, this tale of rural poverty and people eclipsed by a landscape that’s as unforgiving as it is beautiful has an infinitely timeless quality even if this traditional way of life is just as moribund as the bull which drives it.

Tharlo producer Wang Xuebo looks north in this rare cinematic showcase for China’s Hui people, a largely Muslim ethnic group concentrated in the rural North West. Using a cast of non-professional actors, Knife in the Clear Water (清水里的刀子, Qingshui Li De Daozi) marries a neorealist aesthetic with a Tarkovskian poetry as a widowed man faces the coming end of his own life largely through his self identification with his faithful bull, about to be sacrificed in the name of dead for the pleasure of the living. Setting religion to one side, this tale of rural poverty and people eclipsed by a landscape that’s as unforgiving as it is beautiful has an infinitely timeless quality even if this traditional way of life is just as moribund as the bull which drives it.