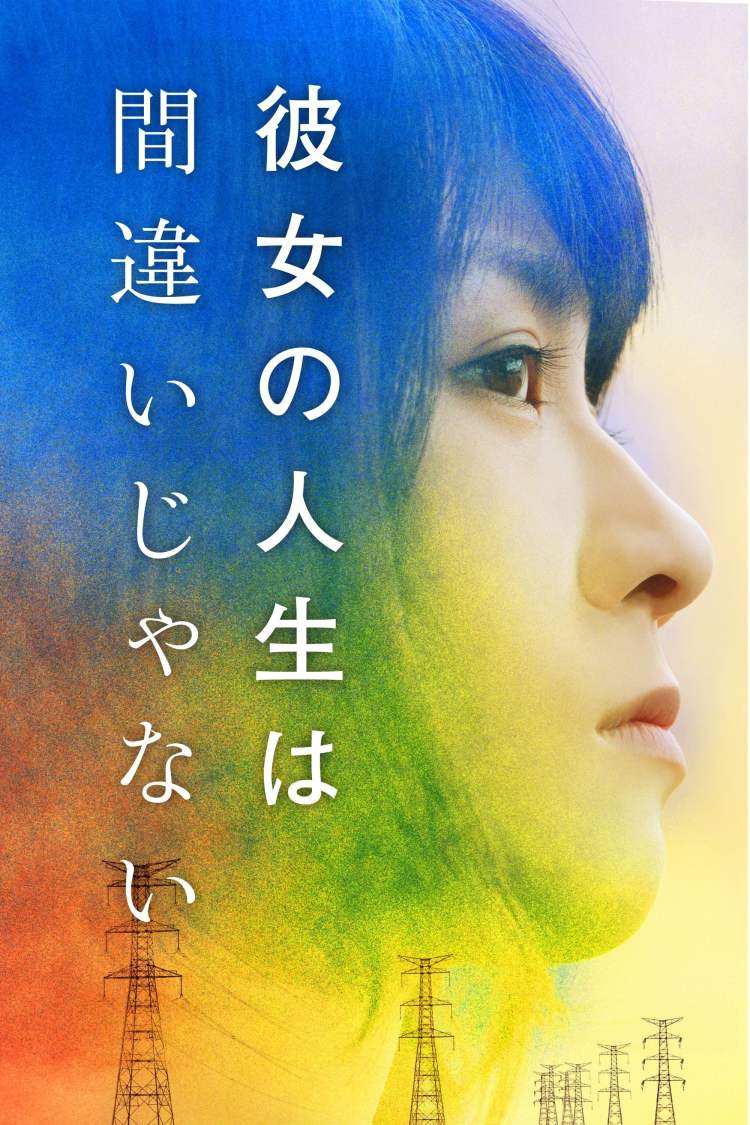

Middle-aged malaise is fast becoming a dominant theme in Chinese language cinema, but the pressures faced by the heroine of the debut feature from Ip Man screenwriter Chan Tai-lee are compounded by a series of additional responsibilities and the relative lack of support available to help her cope with them. Tomorrow is Another Day (黃金花) is, in many ways, a family drama with a sympathetic depiction of the demands of caring for a child with special needs at its centre, but it’s also the story of a marriage and of the essential bonds between a mother and a son as the family struggles to survive in a sometimes hostile environment.

Middle-aged malaise is fast becoming a dominant theme in Chinese language cinema, but the pressures faced by the heroine of the debut feature from Ip Man screenwriter Chan Tai-lee are compounded by a series of additional responsibilities and the relative lack of support available to help her cope with them. Tomorrow is Another Day (黃金花) is, in many ways, a family drama with a sympathetic depiction of the demands of caring for a child with special needs at its centre, but it’s also the story of a marriage and of the essential bonds between a mother and a son as the family struggles to survive in a sometimes hostile environment.

Mrs. Wong (Teresa Mo), interviewed at a community centre, relates the routines of her daily life to a camera crew. Describing herself as a “regular housewife”, Mrs. Wong’s existence revolves around caring for her husband (Ray Lui) – a driving instructor, and her 20-year-old autistic son, Kwong (Ling Man-lung). She tells the film crew she is happy with her life and on one level she is, but she also fears her philandering husband is up to his old tricks again. Mr. Wong is indeed having an affair with one of his pupils, a much younger nurse called Daisy (Bonnie Xian Seli) who seems to have well and truly got her hooks into him. Knowing of her husband’s string of extra-marital affairs which has spanned the entirety of the marriage, Mrs. Wong has made a decision to turn a blind eye for the sake of her son but this latest dalliance has proved difficult for her to bear. After Daisy randomly invites herself into the family home when Mrs. Wong is shopping, the couple argue and Mr. Wong walks out leaving Mrs. Wong to care for Kwong all alone.

Kwong, usually cheerful and well behaved, experiences occasional meltdowns when told he can’t have something that he wants, often resorting to frustrated acts of self harm including bashing his head against nearby solid objects. Though Kwong is not violent towards others, he is now a grown man and much stronger than his mother who finds it difficult to help him calm down on her own. Mr. Wong’s forearms are a mess of scars and bruises received whilst trying to restrain his son from hurting himself, and the physical strain of caring him has often weighed heavy on his conflicted father’s mind.

Though Mrs. Wong and Kwong experience frequent discrimination from those who are unaware of his needs – other mothers pull their children out of the playground when Kwong comes to play, and Mrs. Wong finds it difficult to get a part-time job when her prospective employers spot Kwong standing beside her, the other neighbourhood housewives have become used to Kwong’s way of being and are keen to help out where they can. Like Mrs. Wong, many of the other women have their own problems whether worrying about the (lack of) academic progress of their sons, or trying to combat the potential loneliness of early widowhood through friendship and community. Hearing of Mrs. Wong’s marital problems via the neighbourhood grapevine (another source of humiliation for Mrs. Wong), everyone has taken her side against the villainous Daisy but they’re also worried Mrs. Wong may consider harming herself while faced with so many conflicting pressures.

Mrs. Wong however, has half her mind on revenge and has taken to watching crime documentaries which give her the idea that she could get herself a convenient alibi by going to the Mainland by official means and then smuggling herself back in to off Daisy in the hope that her husband might finally remember his responsibilities. Daisy, it has to be said, is a one note villain and it’s difficult to see why she is so intent on pursuing a dead end romance with a middle-aged, married, driving instructor without coming to the conclusion that she must love causing trouble, especially as Mr. Wong seems to find her quite irritating even once he’s taken the “decision” to leave his family for her. Mr. Wong himself is also a bundle of contradictions but emerges as a weak willed man who has never been able to fully commit to his marriage and struggles with the responsibility involved in being the father of a child with special needs. Though he eventually seems to reconcile himself to his role as his son’s father and his wife’s husband, there is something conceited in his belief that his family will simply take him back when he has caused them so much pain and suffering by his hastily taken decision to abandon them.

Kwong is more perceptive than his mother gives him credit for, and Mrs. Wong too is eventually forced to consider the effect her darkening mindset has had on his emotional wellbeing. Tomorrow is Another Day offers no easy answers in its sympathetic portrayal of a middle-aged woman driven to extremes by a series of conflicting pressures but eventually finds finds comfort in living in the now as the family begins to find its way home, cutting through the noise of a high pressure city to rediscover what it is that’s really important.

Tomorrow is Another Day receives its US premiere as the closing night film of the sixth season of Chicago’s Asian Pop-Up Cinema programme on 16th May, 2018. The screening begins at 7pm, AMC River East 21 and tickets are already on sale via the official website.

Asian Pop-Up Cinema will return for the seventh season in the autumn – make sure you’re up to date with all the latest information by following the festival on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Vimeo.

Original trailer (Cantonese with English/Traditional Chinese subtitles)