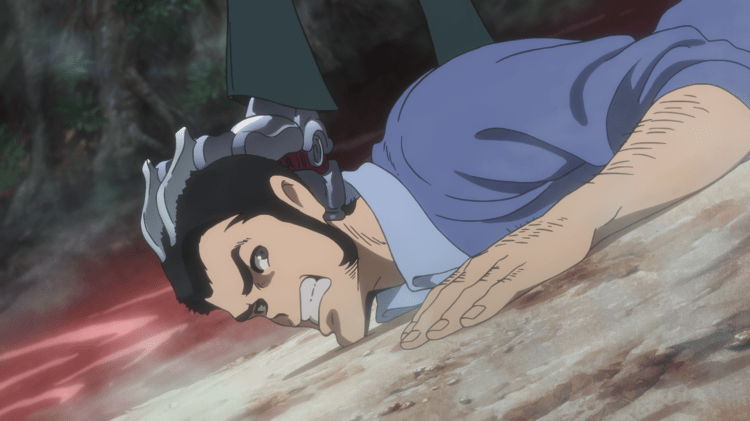

Jung-hwan’s (Jo Jung-suk) daughter Soo-a (Choi Yu-ri) is growing up. She’s no longer enthused about going to the amusement park for her birthday and wishes her father would stop buying churros to mark the occasion. Maybe there’s a part of Jung-hwan that’s frightened of this development, no longer quite knowing who his teenage daughter is becoming and confused by her moodiness. When she’s bitten during the zombie epidemic, however, it might be Jung-hwan who’s bitten off more than he can chew in deciding to hide her from the authorities in the hope she might get “better”.

More family drama than horror movie, Pil Gam-seong’s webtoon adaptation My Daughter is a Zombie (좀비딸, Jombittal) is on one level about unconditional parental love as Jung-hwan refuses to give up on Soo-a and continues to “train” her to regain her memories. With echoes of another pandemic, the film considers society’s reaction to “infectees” who are rounded up and killed to stop the threat of the infection. On returning to his rural hometown to live with his mother, Jung-hwan reunites with a childhood friend, Yeon-hwa (Cho Yeo-jeong), who has since become a teacher, but she has a pathological hated of zombies and until recently had made a point of beating them to death with her kendo sword. Still carrying the trauma of having to kill her fiancé who attacked her, Yeon-hwa doesn’t want to accept that Soo-a could be getting better because that would mean the “zombies” she killed were just people who were ill and could have recovered if she hadn’t murdered them out of rage and prejudice. Indeed, once the infection calms down, the relatives of people killed by state forces begin to ask questions and protest that their loved ones shouldn’t have been treated with such cruel indifference.

Then again, in terms of zombie movies, people who suggest that perhaps they should give the infected a chance rather than proactively killing them don’t usually last very long. The film takes place in a universe in which zombie movies exist with Train to Busan even getting a name check, but none of that’s very helpful to Jung-hwan as he tries to figure out how to keep his daughter safe while also trying to heal her. His job as a tiger trainer seems to come in handy in trying to navigate Soo-a’s new aggressive nature, while his mother Bam-soon (Lee Jung-eun) mostly makes use of her god-given granny powers and a wooden spoon to keep Soo-a in line.

Meanwhile, the promise of a cure and treatment in America is waged agains the vast bounty the government is offering as a reward for turning in zombies. A not so friendly face shows up and tries to kidnap Soo-a for the reward money while even crassly suggesting to Jung-hwan that they split it between them when he tries to intervene and get Soo-a back. In healing Soo-a back to health, Jung-hwan is both attempting to repay a debt and assert himself as Soo-a’s father by essentially rebooting her so that she recovers the shared memories of her childhood.

To that extent, Soo-a’s time as a zombie is a kind of express adolescence in which she travels from grunting teenager to a young woman with a better appreciation for her father and the trouble he went to raise her. Of course, one could say that it’s all a little patriarchal and perhaps Jung-hwan is “taming” her to fit his own image of what his daughter should be much as he tamed the tiger and taught it to dance, but then again Soo-a is also readjusting herself and trying to figure out how to be a person in her own right after moving to her father’s rural hometown where she’s badgered into attending the local school despite her “illness” because there are only four other pupils and otherwise it’s going to have to close. The village is very proud of its current zero infections record, but the funny this they’re all very accepting of Soo-a, though they just think she’s a bit different rather than a “zombie” after buying Jung-hwan’s possibly uncomfortable excuse that she suffered brain damage in an accident. A father’s undying love does, however, eventually save the world after a continual process of being wounded by his daughter and healing again gives Jung-hwan a means to beat the disease if only in his refusal to give up on the idea his daughter will eventually recover.

Trailer (English subtitles)