Kon Ichikawa, wry commenter of his times, turns his ironic eyes to the inherent sexism of the 1960s with a farcical tale of a philandering husband suddenly confronted with the betrayed disappointment of his many mistresses who’ve come together with one aim in mind – his death! Scripted by Natto Wada (Ichikawa’s wife and frequent screenwriter until her retirement in 1965), Ten Dark Women (黒い十人の女, Kuroi Junin no Onna) is an absurd noir-tinged comedy about 10 women who love one man so much that they all want him dead, or at any rate just not alive with one of the others.

Kon Ichikawa, wry commenter of his times, turns his ironic eyes to the inherent sexism of the 1960s with a farcical tale of a philandering husband suddenly confronted with the betrayed disappointment of his many mistresses who’ve come together with one aim in mind – his death! Scripted by Natto Wada (Ichikawa’s wife and frequent screenwriter until her retirement in 1965), Ten Dark Women (黒い十人の女, Kuroi Junin no Onna) is an absurd noir-tinged comedy about 10 women who love one man so much that they all want him dead, or at any rate just not alive with one of the others.

Kaze (Eiji Funakoshi) is a TV producer by profession, though it might be better to think of him as a professional ladies’ man. He’s married to a woman who owns a bar, but is also carrying on affairs with nine (!) other women plus occasional one night stands with 30-50 others he meets through his work. His wife knows about his affairs and, while not happy about it, is putting up with things like decent wives are supposed to do. However, many of Kaze’s “mistresses” have inconveniently discovered each other’s existences and bonded in their mutual frustration with him. Strangely they all think he’s a great guy and remain very much in love with him but the situation being what it is the entirety of the betrayed wife and mistress support club eventually comes to the same conclusion – Kaze must die!

However, the women are all so devoted to Kaze, they don’t quite want him to disappear so much as for him to pick them and only them to live with happily ever after. One of the women foolishly warns Kaze about their plot as leverage for her marriage proposal but unfortunately for her he still turns her down and returns home to ask his wife what’s going on. She doesn’t deny her murderous intentions and in fact tells him in great detail how they intend to do him in. Kaze, to his credit, says he doesn’t mind very much and only worries about his wife’s future life as a murderess. Together they hatch a plan to fool the other women involving a pistol loaded with blanks and a tomato but nothing quite goes to plan.

An absurdist satire about the intense vanity of the womanising male, Ten Dark Women looks forward to Fellini’s similarly themed 8 1/2 or City of Women though here the idiotic husband at the centre becomes both prey and foil for the group of plotting women seeking revenge against his disloyal ways. Kaze, as he himself admits, is not particularly appealing to women though his position at the TV studio undoubtedly proves useful to some of them. He’s a curiously passive presence, not so much seeking out female company as acquiescing to it. It’s not quite clear if his concern for his wife should she decide to kill him is genuine or a means of manipulative self preservation but at any rate he takes the threat to his life extremely calmly.

Each of the women has their own claims on Kaze but the other thing they all have in common is being the prisoner of an extremely sexist society. Some of the women are with Kaze for careerist reasons, but it’s clear that there is a definite limit placed on a woman’s potential both inside and out of the creative industries. The commercial model makes a play for a more official relationship by bringing up the fact that Kaze’s wife has a job and therefore cannot devote herself entirely to Kaze’s wellbeing as proper wife should (as by implication would she after marrying and retiring from the modelling world). Kaze helped his wife set up her bar which she runs herself though constantly plays hostess to her husband’s industry friends. It appears what Kaze wants is less a devoted wife than an indifferent one who will permit his frequent “indiscretions” whilst also providing him with a conventional “home”.

Another of the women tries to get herself a promotion but her boss, though broadly sympathetic and dangling the idea of a raise, brings up the oft repeated notion that there’s no sense in giving her the job because a woman should leave at some point to marry and have children. When the woman criticises the behaviour of her male colleagues, her boss simply shrugs and admits men in TV aren’t “serious”, yet when she points out that she is serious and works hard she is told that women are better off at home. Women, he says, express themselves through their children whereas men make their mark through a career. The woman says that she believes everyone should try to reach their own potential in whatever way they can but her pleas fall on deaf ears. This notion is repeated later on when the women try to take revenge on Kaze by tricking him into resigning from his job – a man is his work, he claims. A man without a job is nothing at all and a man who is kept by a woman is less than nothing – Kaze is suddenly panicked, losing his occupation and social position is much more frightening to him than losing his life.

The women couldn’t kill the system or the TV, but they could kill Kaze so who can blame them for trying. Another of the women states that the imposed isolation of a man’s working life has cost him the ability to connect with other people on a human level and so his erasure is simply the end of a long process of social death. If some of the women triumph, others retreat as one does in suicide only to return as a ghost longing for the murder plot to succeed so that she and Kaze can be alone together at last. Kaze thinks he’s using each of them, but they have all been using him in one way or another and his only way out lies either in death or becoming a trophy for the most needy of his paramours.

Cynical in tone, Ten Dark Women is an amusingly absurd look at gender roles in early 1960s Japan as each of our women attempts to usurp male power for their own ends, some with more success than others. Ichikawa employs beautiful noir lighting in his elegantly composed black and white photography which, along with its jazzy score, gives the film a familiar feeling of crime laced modernity. An early instance of the feminist revenge film, Ten Dark Women is very much a comedy which avoids making its group of frustrated, resentful women mistreated by a buffoon of a TV exec the butt of its own joke, neatly highlighting the precarious nature of their existence which obliges them to rely on so hollow a support.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

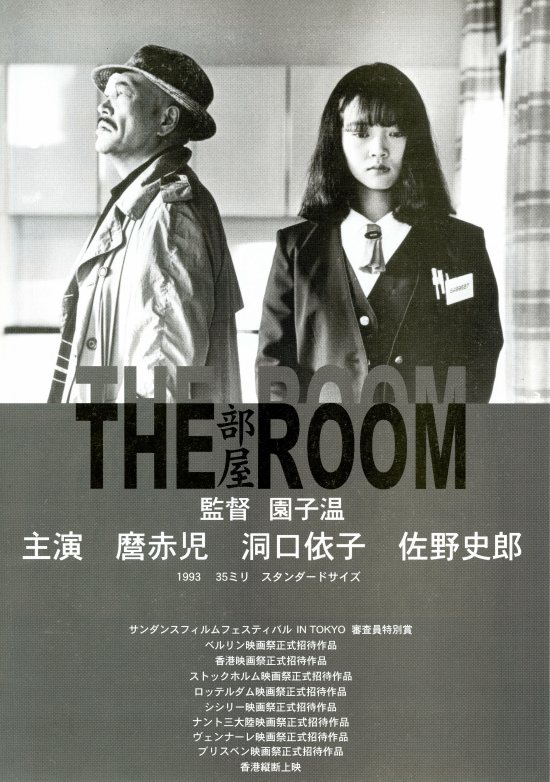

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection.

The second of the only three extant films directed by Sadao Yamanaka in his intense yet brief career, Kochiyama Soshun (河内山宗俊, oddly retitled “Preist of Darkness” in its English language release) is not as obviously comic or as desperately bleak as the other two but falls somewhere in between with its meandering tale of a stolen (ceremonial) knife which precedes to carve a deep wound into the lives of everyone connected with it. Once again taking place within the realm of the jidaigeki, Kochiyama Soshun focuses more tightly on the lives of the dispossessed, downtrodden, and criminal who invoke their own downfall by attempting to repurpose and misuse the samurai’s symbol of his power, only to find it hollow and void of protection.

Hiroshi Shimizu is often remembered for his talent as a director of children, something which he brings to the fore with his melancholy meditation on the immediate post-war world in Children of the Beehive (蜂の巣の子供たち, Hachi no Su no Kodmotachi). This is a destroyed society, but one trying to make the best of things, surviving in any way possible. It’s fairly clear from Shimizu’s pre-war work that he did not entirely approve of the way his country was heading. Children of the Beehive seeks not to apportion blame, but merely to make plain that no one can get along alone here, in the post-war world there are only orphans and ruined cities but that itself is an opportunity to rebuild better and kinder than before.

Hiroshi Shimizu is often remembered for his talent as a director of children, something which he brings to the fore with his melancholy meditation on the immediate post-war world in Children of the Beehive (蜂の巣の子供たち, Hachi no Su no Kodmotachi). This is a destroyed society, but one trying to make the best of things, surviving in any way possible. It’s fairly clear from Shimizu’s pre-war work that he did not entirely approve of the way his country was heading. Children of the Beehive seeks not to apportion blame, but merely to make plain that no one can get along alone here, in the post-war world there are only orphans and ruined cities but that itself is an opportunity to rebuild better and kinder than before. Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the

Hibari Misora was one of the leading lights of the post-war entertainment world. Largely active as a chart topping ballad singer, she also made frequent forays into the movies notably starring with fellow musical stars Izumi Yukimura and Chiemi Eri in the  Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years.

Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years. Following on from

Following on from  Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.

Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families. Naruse apparently directed six other films in-between

Naruse apparently directed six other films in-between  Mikio Naruse is often remembered for his female focussed stories of ordinary women trying to do they best they can in often difficult circumstances, but the earliest extant example of his work (actually his ninth film), Flunky, Work Hard (腰弁頑張れ, Koshiben Ganbare), is the sometimes comic but ultimately poignant tale of a lowly insurance salesman struggling to get ahead in depression era Japan.

Mikio Naruse is often remembered for his female focussed stories of ordinary women trying to do they best they can in often difficult circumstances, but the earliest extant example of his work (actually his ninth film), Flunky, Work Hard (腰弁頑張れ, Koshiben Ganbare), is the sometimes comic but ultimately poignant tale of a lowly insurance salesman struggling to get ahead in depression era Japan.