Haruki Kadokawa had become almost synonymous with commercial filmmaking throughout the 1980s and his steady stream of idol-led teen movies was indeed in full swing by 1987, but his idols, as well as his audiences, were perhaps beginning to grow up. Yoichi Sai’s first outing for Kadokawa had been with the typically cheery Someday, Someone Will Be Killed which was inspired by the most genre’s representative author, Jiro Akagawa, and followed the adventures of an upperclass girl who is suddenly plunged into a world of intrigue when her reporter father disappears after dropping a floppy disk into her handbag. A year later he’d skewed darker with a hardboiled yakuza tale starring Tatsuya Fuji as part of Kadokawa’s gritty action line, but he neatly brings to two together in The Lady in a Black Dress (黒いドレスの女, Kuroi Dress no Onna) which features the then 20-year-old star of The Little Girl Who Conquered Time, Tomoyo Harada, in another noir-inflected crime thriller again adapted from a novel by Kenzo Kitakata.

Haruki Kadokawa had become almost synonymous with commercial filmmaking throughout the 1980s and his steady stream of idol-led teen movies was indeed in full swing by 1987, but his idols, as well as his audiences, were perhaps beginning to grow up. Yoichi Sai’s first outing for Kadokawa had been with the typically cheery Someday, Someone Will Be Killed which was inspired by the most genre’s representative author, Jiro Akagawa, and followed the adventures of an upperclass girl who is suddenly plunged into a world of intrigue when her reporter father disappears after dropping a floppy disk into her handbag. A year later he’d skewed darker with a hardboiled yakuza tale starring Tatsuya Fuji as part of Kadokawa’s gritty action line, but he neatly brings to two together in The Lady in a Black Dress (黒いドレスの女, Kuroi Dress no Onna) which features the then 20-year-old star of The Little Girl Who Conquered Time, Tomoyo Harada, in another noir-inflected crime thriller again adapted from a novel by Kenzo Kitakata.

We first meet the titular “lady in a black dress” walking alone alone along a busy motorway until she is kerb crawled by a yakuza in a fancy car. Declaring she intends to walk to Tokyo (a very long way), Reiko (Tomoyo Harada) nevertheless ends up getting into the mysterious man’s vehicle despite avowing that she “hates yakuza”. The yakuza goon does however drive her safely into the city and drop her off at her chosen destination – a race course, where she begins her quest to look for “someone”. By coincidence, the yakuza was also heading to the race course where he intended to stab a rival gangster – Shoji (Bunta Sugawara), who makes no attempt to get away and seemingly allows himself to be stabbed by the younger man. Shoji, as it happens, is the temporary responsibility of the man Reiko has been looking for – Tamura (Toshiyuki Nagashima), a former salaryman turned bar owner with fringe ties to the yakuza. Putting on her little black dress, Reiko finally finds herself at his upscale jazz bar where she petitions him for a job and a place to stay, dropping the name of Tamura’s sister-in-law who apparently advised her to try hiding out with him.

Reiko is, after a fashion, the dame who walked into Tamura’s gin joint with the (mild) intention to cause trouble, but, in keeping with the nature of the material, what she arouses in Tamura and later Shoji is a latent white knight paternalism. Curious enough to rifle through her luggage while she’s out, Tamura is concerned to find a pistol hidden among her belongings but when caught with it, Reiko offers the somewhat dark confession that the gun is less for her “protection” than her suicide. Not quite believing her, Tamura advises Reiko not to try anything like that in his place of business and to take it somewhere else. Nevertheless, Reiko stays in Tamura’s bar, eventually sharing a room with melancholy yakuza Shoji who is also hiding out there until the plan comes together to get him out of the country and away from the rival gangsters out for his blood.

As it turns out, Reiko had good reason to “hate yakuza” but she can’t seem to get away from them even in the city. Tamura’s life has also been ruined by organised crime as we later find out, and it’s these coincidental ties which eventually bring Reiko to him through his embittered sister-in-law who had been the mistress of Reiko’s lecherous step-father. The codes of honour and revenge create their own chaos as Shoji attempts to embrace and avoid his inevitable fate while his trusted underling (the yakuza who gave Reiko a lift) tries to help him – first by an act of symbolic though non-life threatening stabbing and then through a brotherly vow to face him himself to bring the situation to a close in the kindest way possible.

Meanwhile, a storm brews around a missing notebook which supposedly contains all the sordid details of the dodgy business deals brokered by a now corporatised yakuza who, while still engaging in general thuggery, are careful to mediate their world of organised crime through legitimate business enterprises. Reiko, like many a Kadokawa heroine, is an upperclass girl – somewhat sheltered and innocent, but trying to seem less so in order to win support and protection against the forces which are pursuing her. Though the film slots neatly into the “idol” subgenre, Harada takes much less of a leading role than in the studio’s regular idol output, retaining the mysterious air of the “lady in a black dress” while the men fight back against the yakuza only gradually exposing the truths behind the threat posed to Reiko.

Consequently, Reiko occupies a strangely liminal space as an adolescent girl, by turns femme fatale and damsel in distress. Wily and resourceful, Reiko formulates her own plan for getting the gangsters off her back, even if it’s one which may result in a partial compromise rather than victory. Though Kadokawa’s idol movies could be surprisingly dark, The Lady in a Black Dress pushes the genre into more adult territory as Reiko faces quite real dangers including sexual violence while wielding her femininity as a weapon (albeit inexpertly) – something quite unthinkable in the generally innocent idol movie world in which the heroine’s safety is always assured. Sai reframes the idol drama as a hardboiled B-movie noir scored by sophisticated jazz and peopled by melancholy barmen and worn-out yakuza weighed down by life’s regrets, while occasionally switching back to Reiko who attempts to bury her fear and anxiety by dancing furiously in a very hip 1987 nightclub. Darker than Kadokawa’s generally “cute” tales of plucky heroines and completely devoid of musical sequences (Harada does not sing nor provide the theme tune), The Lady in a Black dress is a surprisingly mature crime drama which nevertheless makes room for its heroine’s eventual triumph and subsequent exit from the murky Tokyo underground for the brighter skies of her more natural environment.

TV spot (no subtitles)

Theme song – Kuroi Dress no Onna -Ritual- by dip in the pool.

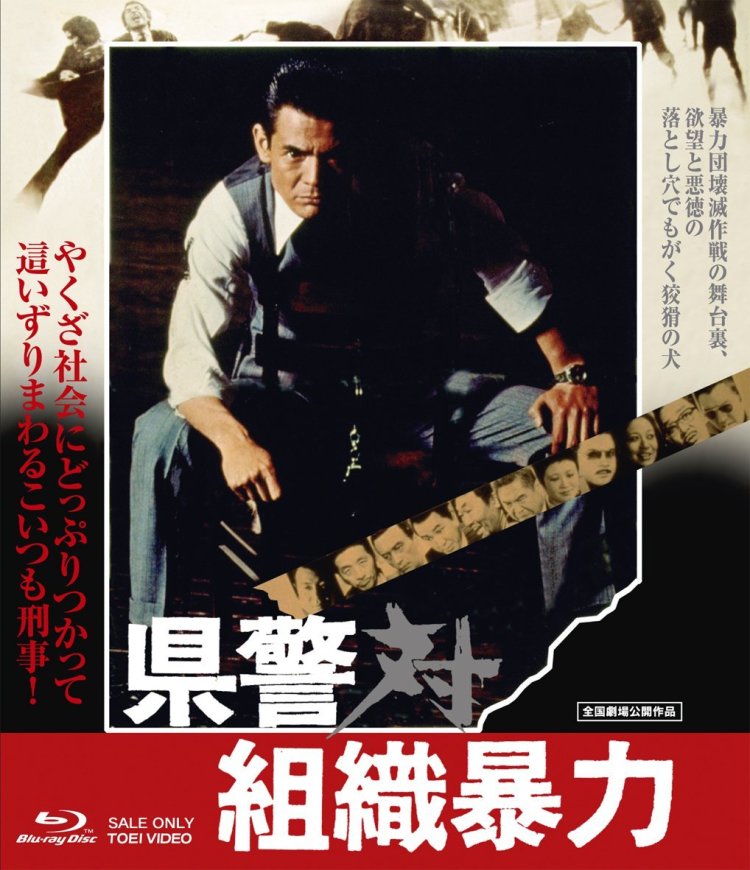

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first

Cops vs Thugs – a battle fraught with friendly fire. Arising from additional research conducted for the first  Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,

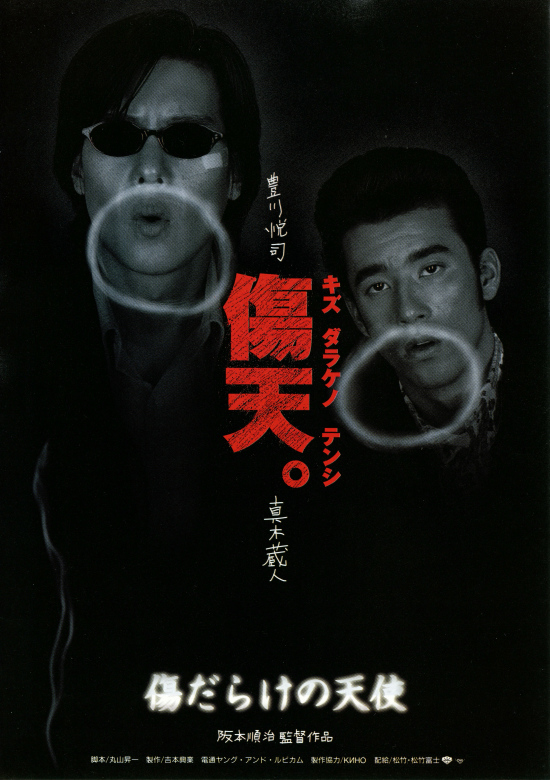

Masahiro Shinoda’s first film for Shochiku,  Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture

Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture  Japanese cinema has not been as shy as might be supposed in examining uncomfortable topics concerning the nation’s mid 20th century history but perhaps prefers to tackle them from a subtle, sideways viewpoint. By a Man’s Face Shall You Know Him (男の顔は履歴書, Otokonokao wa Rirekisho) is, in essence, a fairly straightforward gangster pic – save that the rampaging gangsters are a mob of “zainichi” Koreans rather than post-war yakuza or petty hoodlums. Less about what it is to be an outsider or the quest for identity in second generation immigrants, Kato’s film is about what it says it is about – a man’s face.

Japanese cinema has not been as shy as might be supposed in examining uncomfortable topics concerning the nation’s mid 20th century history but perhaps prefers to tackle them from a subtle, sideways viewpoint. By a Man’s Face Shall You Know Him (男の顔は履歴書, Otokonokao wa Rirekisho) is, in essence, a fairly straightforward gangster pic – save that the rampaging gangsters are a mob of “zainichi” Koreans rather than post-war yakuza or petty hoodlums. Less about what it is to be an outsider or the quest for identity in second generation immigrants, Kato’s film is about what it says it is about – a man’s face.

And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best.

And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best. It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war.

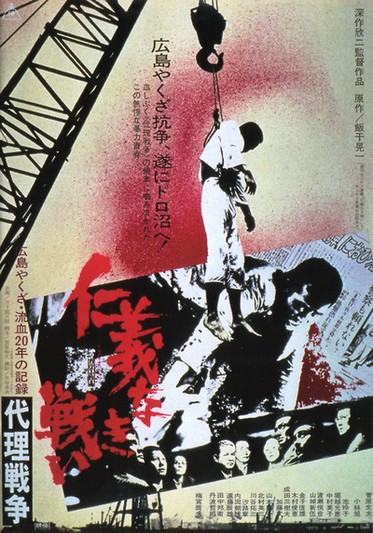

It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war. Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.