“Customer-centric”, what does that actually mean? The Amazon-like US-based conglomerate at the centre of Ayako Tsukahara’s Last Mile (ラストマイル) prides itself on its customer-centric philosophy, but at the end of the day, what that really means is that they give us what we tell them we want through our purchasing patterns and browsing history. That would be that we want everything as cheap and fast as it’s possible to be and don’t really think about the wider implications or what a world of infinite convenience might be doing to the society around us.

At least from the perspective of corporate lackey Elena (Hikari Mitsushima), recently returned from the US, the reason Daily Fast pressures its delivery staff to lower costs isn’t to maximise their profits, it’s so they can go on providing lower prices to customers which to her is all part of their customer-centric approach. This doesn’t really gel with her off-the-cuff remark about the warehouse not having a safety net to protect the workers from accidental falls or, she ominously adds, prevent people from jumping. That she brought it up at all might signal that she knows something’s not quite with the way this company treats its employees, though as it turns out she may have something else on her mind. In any case, when she arrives on her very first day the entrance to the complex is little better than a cattle market with a man on loud speaker barking instructions about were to go to the 800 members of staff some of whom have only been brought in to bulk up for the upcoming Black Friday sale.

Which is all to say, it wouldn’t be all that surprising if the fact that some of their parcels have been exploding on delivery were a concerted attack against their ultra-capitalist philosophy, though actively delivering bombs to people who didn’t order them is not very “customer-centric” in any case. Obviously, Elena isn’t keen on this either but is also convinced that it can’t really be their fault because they have strict and dehumanising security measures in place preventing the workers from bringing in anything inessential. Even after she works out that the bomber has actually warned them that there are 12 bombs out there, she wilfully withholds the evidence from law enforcement to avoid damaging their share prices while trying to minimise business interruption rather than do anything sensible like stop delivering people parcels until they’ve figured out what’s going on with the bombs, though the real mystery is why the police don’t really seem to have the power to do that and, in fact, end up working with the warehouse to check each parcel individually to keep the conveyor belts going.

From the aerial view, the city itself resembles the warehouse with the roads taking the place of the belts as delivery vans shuttle along them. Seventy-something delivery driver subcontractor Sano (Shohei Hino) once had a friend who used to say that they were the ones who kept the country running. Yacchan became the number one driver largely because he took 10 minutes to eat his lunch and worked every hour god sent for dwindling pay with the implication that his gruelling schedule contributed to his early death. Sano’s son Wataru (Shôhei Uno) has just started working with him on the van after being laid off from an electronics job. They made quality washing machines that were designed to be efficient and to last, but of course they couldn’t compete with cheaper brands so they went bust.

Elena berates herself for being “too Japanese” for the American company which is to say that she takes pride in her work. That’s not to say that everything about the American business culture is bad as she encourages her assistant, Ko (Hikari Mitsushima), to call her Elena and to feel free to speak his mind rather than equivocate to avoid causing offence. But despite their “customer-centric” approach, it’s clear that the company puts profits above all else and treats its workers, who are not actually employees, poorly, without concern for their wellbeing. Yagi (Sadao Abe), the boss of logistics first Sheep Express which is the prime courier for Daily Fast, laments that he’d love to hire more drivers to help them through this crisis but he can’t because they’re always squeezing his budget and no one will work for their terrible rates except for those who, like Sheep Express itself, have no other options and will have put up with it because they’re dependent on Daily Fast. And because they’re dependent on Daily Fast, it means we all have to keep buying stuff we don’t really want or need just keep the belts going because we’re terrified about what will happen if they stop.

There is a direct comparison between Wataru’s well-made washing machines and the cheap and fast consumerist model that’s gradually taken over that suggests things like craftsmanship and integrity have gone out the window in a world where no one really bothers to go the last mile anymore, though it’s his steadfast engineering that eventually saves the day while even Elena comes to rethink her career trajectory and advises the drivers to strike and end this culture of exploitation because it turns out Daily Fast needs them more than they need Daily Fast. But maybe we don’t really need Daily Fast either, and we’re as much to blame for letting them give us what we think we want without really considering what that actually means. Perhaps a “customer-centric” society’s not all it’s cracked up to be, especially when workers and consumers are often the same people stuck on conveyor belts knowing there’s only one way to stop them.

Last Mile screens 19th June as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Trailer (no subtitles)

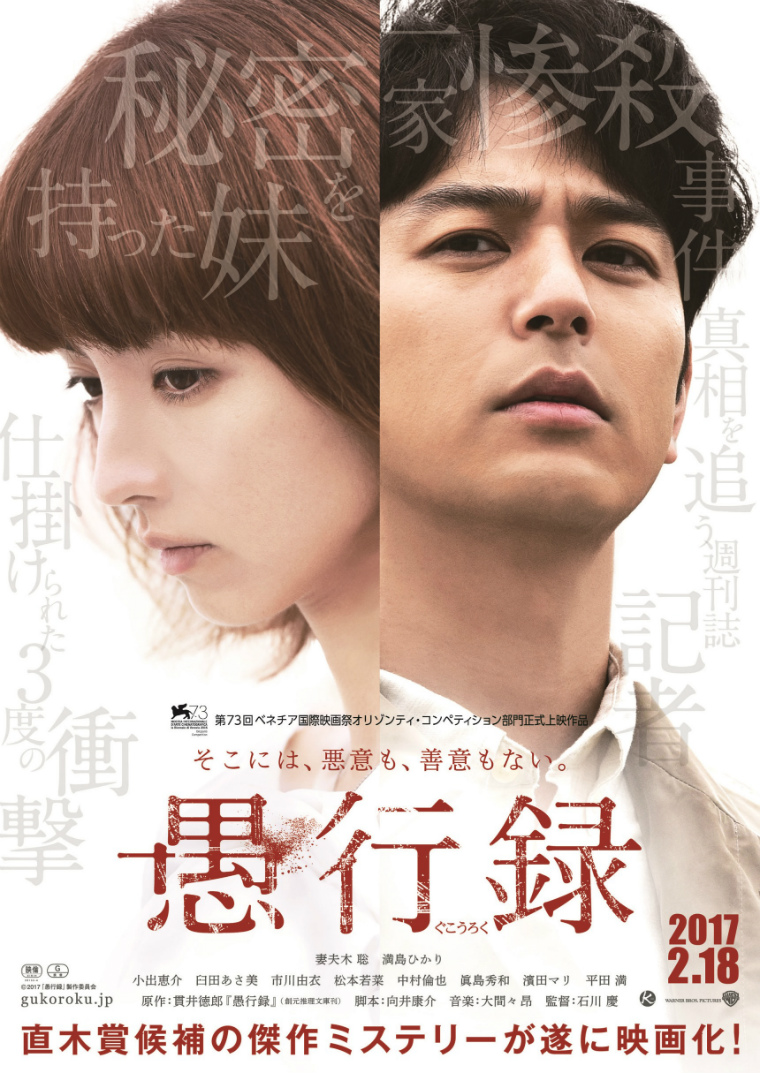

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society.

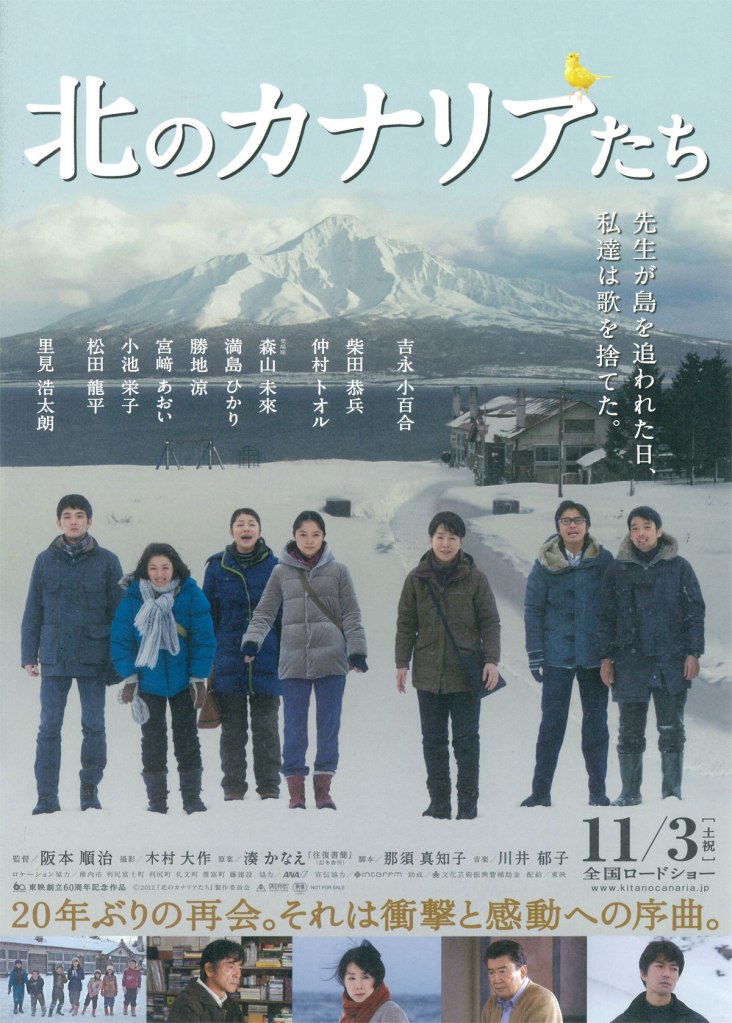

Generally speaking, murder mysteries progress along a clearly defined path at the end of which stands the killer. The path to reach him is his motive, a rational explanation for an irrational act. Yet, looking deeper there’s usually something else going on. It’s easy to blame society, or politics, or the economy but all of these things can be mitigating factors when it comes to considering the motives for a crime. Gukoroku – Traces of Sin (愚行録), the debut feature from Kei Ishikawa and an adaptation of a novel by Tokuro Nukui, shows us a world defined by unfairness and injustice, in which there are no good people, only the embittered, the jealous, and the hopelessly broken. Less about the murder of a family than the murder of the family, Gukoroku’s social prognosis is a bleak one which leaves little room for hope in an increasingly unfair society. As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives.

As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives. The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go.

The world of the classical “jidaigeki” or period film often paints an idealised portrait of Japan’s historical Edo era with its brave samurai who live for nothing outside of their lord and their code. Even when examining something as traumatic as forbidden love and double suicide, the jidaigeki generally presents them in terms of theatrical tragedy rather than naturalistic drama. Whatever the cinematic case may be, life in Edo era Japan could be harsh – especially if you’re a woman. Enjoying relatively few individual rights, a woman was legally the property of her husband or his clan and could not petition for divorce on her own behalf (though a man could simply divorce his wife with little more than words). The Tokeiji Temple exists for just this reason, as a refuge for women who need to escape a dangerous situation and have nowhere else to go.