“The one holding the money calls the shots,” according to a particularly sticky debtor in Sadaaki Haginiwa’s The King of Minami, though that turns out not quite to be the case. After all, though the money may be in his possession, technically it belongs to Ginjiro (Riki Takeuchi) and when they don’t return it to him, he begins to feel offended. Reflective of a kind of post-bubble malaise, the film has a rather cynical take on money and finance, but at the same time a weird kind of wholesomeness.

Ginjiro may be the King of Minami, but he sees himself as a saviour of the poor. Questioned by new underling Ryuichi, he brushes off concerns that people can be driven to suicide over debt by claiming that the loans he offers may save their lives. But though Ginjiro may claim to be somehow better than his yakuza counterparts in refusing to resort to violence, he’s ruthless in other ways and certain that debts must be repaid. Once he’s cheated by an old man, Tokugawa, who refuses to pay the interest on his loan, Ginjiro knows theres’s no point pressing him and decides to go after his daughter instead. She, however, has already maxed out all her card trying to save her dad’s business.

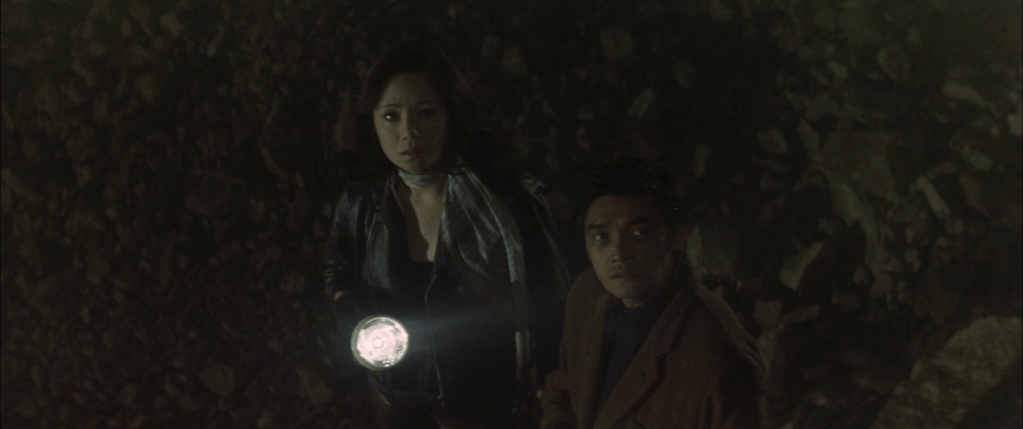

For his righteousness, explaining that he’ll never end up with sometime love interest Asako because a loan shark has no room for relationships, Ginjiro’s world is essentially misogynistic. Sent after a runaway bar hostess, Ginjiro tells Ryuichi that women always have ways of making money with a note of envy in his voice as if he resented this essential unfairness on behalf of impoverished men. Of course, this way of making money is open to them too, though they wouldn’t consider it and no one would put it forward as an option or view their body as a commodity that should be traded away when one has debts. He says something similar to Tokunaga’s schoolteacher daughter Machiko too, agreeing that night work is the way to make a lot of money relatively quickly. Machiko has, however, already been forced into sexual slavery by Narita, a rival yakuza loanshark, who extorts sexual favours in lieu of money.

Young Ryuichi is quite touched by her story and even falls in love with her a little bot despite Ginjiro’s warnings that a loanshark can’t afford to let his emotions overcome his reason. Even if he remains willing to make Machiko pay for her father’s transgressions, Ginjiro is equally angry with Tokunaga for rejecting this essential law that money should always find its way to its point of origin. Taking him to task for his immoral vices such as a gambling addiction that’s ruined his business, finances, and relationships, Ginjiro tells him that he ought to pay his debts himself rather than push them on his daughter. He seems to have contempt for people who do this to themselves through what he sees as their own poor choices, but less so for those like Machiko who end up needing his services through no fault of their own or an ironic sense of indebtedness to someone else.

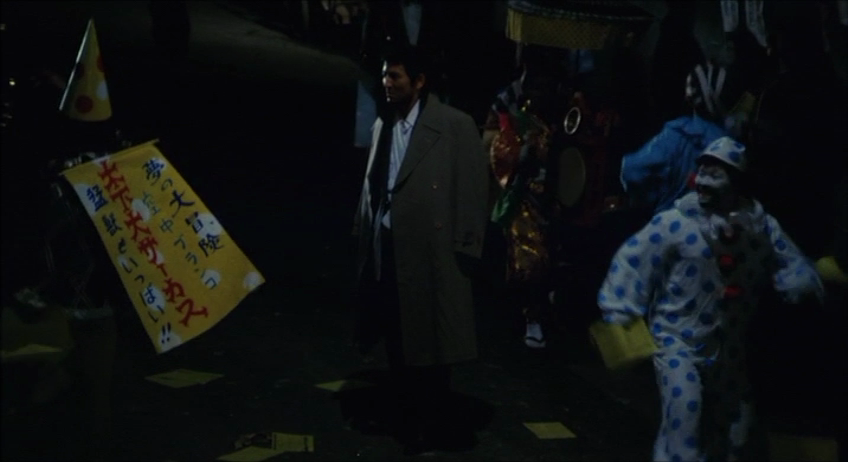

In any case, he stands a kind of counter to those like Narita who only want to exploit people’s weaknesses and use violence to get their way. The two of them end up in a financial sparring match as Narita sets Girjio up with a deliberately bad debt, while he, in turn, masterminds a counter scam under the tutelage of his “financial teacher” who knows all sorts of underhanded ways to make money like selling land that doesn’t belong to you. One could say that he’s teaching Ryuichi all the wrong lessons, but then his behaviour is more roguish than dangerous and he’s obviously more morally righteous than the sneering Narita who seems to feed off human pain so it’s satisfying to see him win and humiliate the predatory yakuza. Ginjiro agrees that it’s a sad world in which people die over money, but, at the same time, has a healthy disregard for it. He tells Ryuichi that he should think of money in the same as a greengrocer thinks of vegetables and that he needs to lose his reverence for it if he’s to make it as a loanshark. That might, after all, be how he became the king of Minami, laughing at the ridiculousness of a world in which those with money call the shots while simultaneously holding all the cards himself.