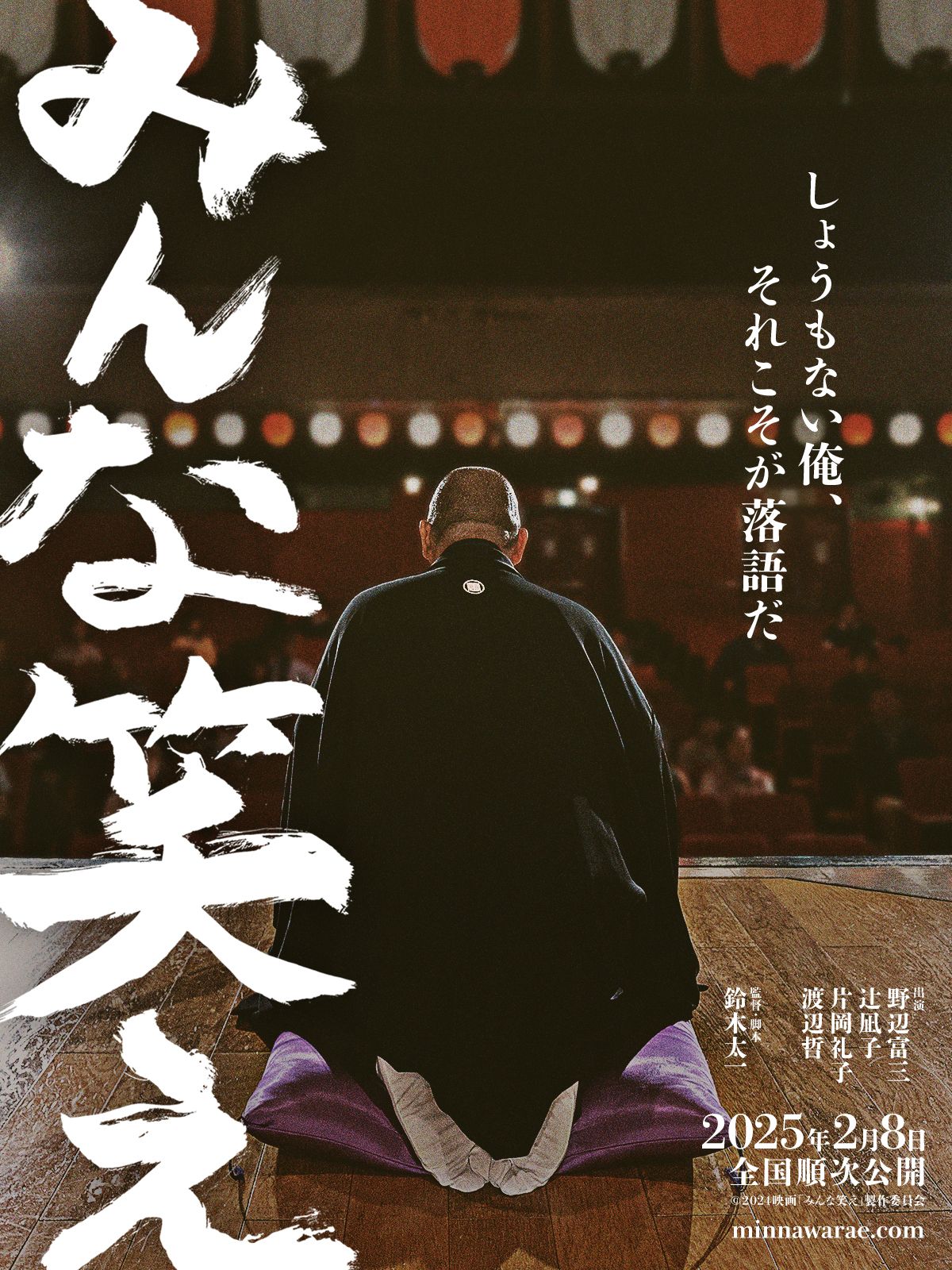

A down of his luck second generation rakugo storyteller begins to discover a new way of life after meeting an aspiring female comedian in Taichi Suzuki’s lighthearted dramedy, Laugh, Everyone! (みんな笑え, Minna Waremashit). The title is taken from a moment of madness in which a resurgent Tamon pleads for everyone to just laugh rather than being at each other’s throats or feeling like they want to die, but that’s something he himself may not be able to do until he’s truly made peace with his demons.

Chief among them would be his father, Kenzo, a rakugo master who’s tormented and bullied him his whole life. In general, rakugo storytellers recite a canon of classical tales that have been passed down since the Edo era, but despite having inherited his father’s stage name, Tamon avoids performing the classical repertoire and sticks to original material. His acts don’t seem to please the audience, and it’s clear that his father’s other disciple, Kannosuke, resents that it was Tamon who became the official heir despite having no talent when he was the rightful successor. Unfortunately, Kanzo failed to plan for his retirement and now has dementia, meaning that he can no longer perform. Unable to make money through rakugo, Tamon has a part-time job in a warehouse to try to make ends meet all while being berated by Kanzo for bing a useless failure.

There are some touching moments later on in which Kanzo bonds with the son of his carer and plays with him as if he were Tamon, hinting that he might have liked to have been a different kind of father and have a different kind of life if it were not for the pressure of passing on his rakugo name. For his part, Tamon has become timid in the extreme and has been running away from anything challenging or unpleasant his whole life. In fear of not living up to his father’s legacy, Tamon avoids the old stories and sticks to telling the same original tale he’s been doing for the last 30 years.

But if his problem is that he can’t master the classics, Kiko’s is that she can’t innovate and all her original material is pinched from somewhere else. She and her comedy double act partner Chi-chan have been trying to break into television, but can’t catch a break with their largely improvised act. While auditioning, they encounter entrenched sexism as the male panellist tells them that women aren’t funny and don’t take comedy seriously. Kiko’s mother Yoko experiences something similar at her bar where her sleazy backer is all over a younger hostess with whom he eventually hopes to replace her, while Chi-chan has also fallen prey to a predatory man working at a host club. She has been financially supporting Joe to help him achieve his dream while he forces her into sex work to make him more money, pushing her to quit comedy and work for him full-time. This kind of exploitation has regrettably become so common that a specific law was passed in 2025 to prevent young male “hosts”, who work in bars where they charm women into buying drinks and gifts, forcing their patrons into debt and then sexual exploitation.

Nevertheless, Kiko strikes gold when she hears Tamon’s baseball-themed routine and realises it’s the same one her mother used to listen to on cassette tape. Reworking it as a manzai routine, she sees a way through her creative block even if it’s sort of plagiarism. After getting his permission to use his material, Kiko begins to think of Tamon as a mentor while he almost thinks the same of her as they encourage each other through their comedic failures even while working in opposite directions. A kind of rapport emerges between them as they were actually an accidental manzai double act along with a more positive paternal relationship than that seen between Kanzo and Tamon which is fuelled by a fear of obsolescence, ego, and resentment. Through his friendship with Kiko and rekindling that with her mother, Tamon eventually gains the courage to stop running away and face himself in classic rakugo both making peace with the complicated relationship he had with his father and carving out a new identity for himself in emerging from his father’s shadow. Sparrows fleeing the cage, both he and Kiko rediscover the healing power of laughter and with it the courage to face their troubles head on rather than continuing to run away in fear of failure and miss out on the joy the craft can bring to those around them.

Laugh, Everyone! is available to stream until 14th September 2025 courtesy of Chicago Japan Film Collective.

Trailer (English subtitles)