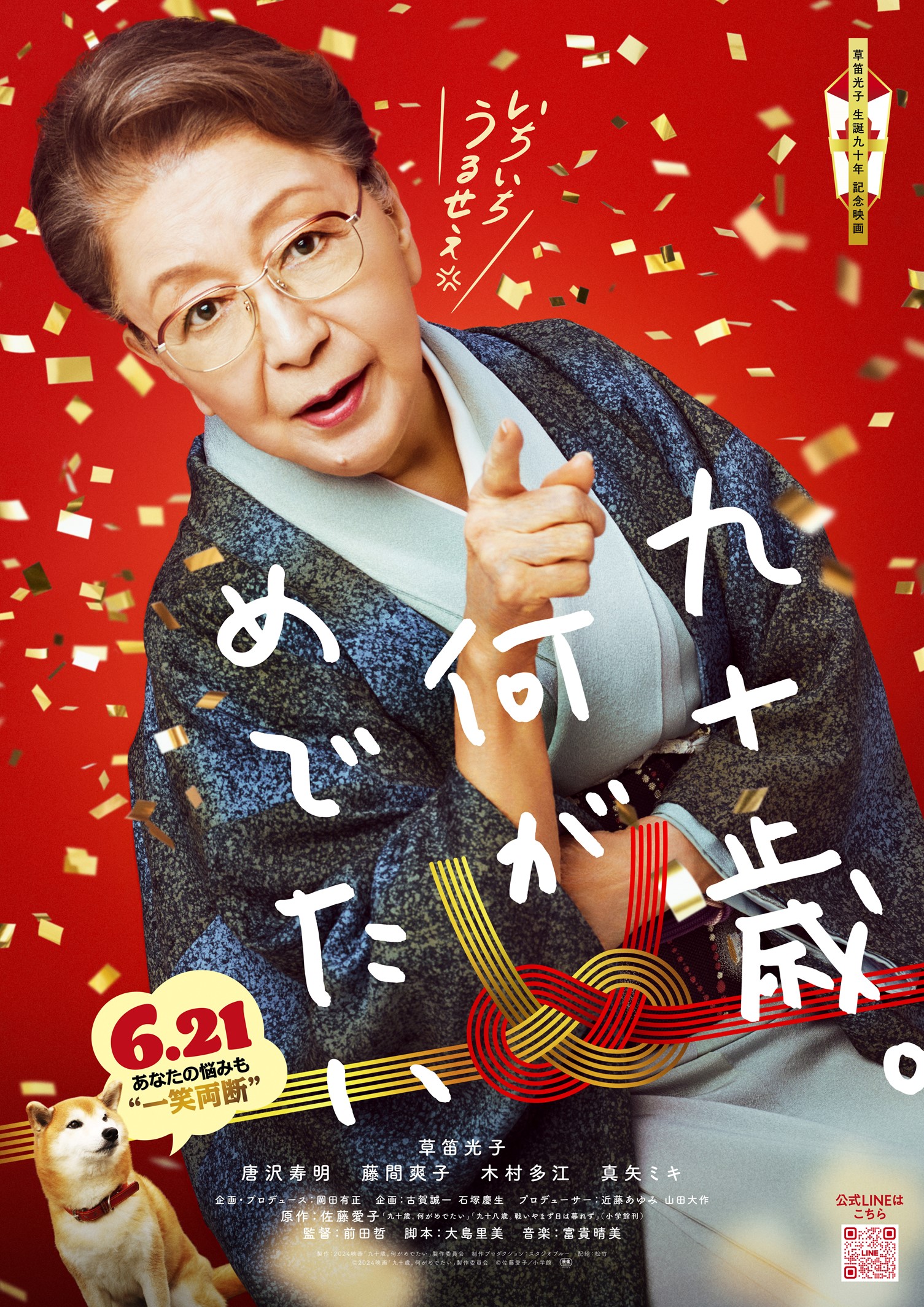

Everyone keeps congratulating Aiko Sato (Mitsuko Kusabue) on reaching 90, but she can’t see what’s so special about it. Having retired from writing after publishing her last novel at 88, she’s really feeling her age and has little desire to anything but sit around waiting to die. That is, until she’s badgered into picking up her pen by a down on his luck, “dinosaur” editor certain that her words of wisdom will strike a chord with the young people of today.

Marking the 90th birthday of its leading lady Mitsuko Kusabue and directed by comedy master Tetsu Maeda, the film takes its name from a collection of essays published under the title “90 Years Old, So What?” which largely deal with what it’s like to be old in the contemporary society along with the way things have changed or not in Japan over the last 90 years. It does not, however, shy away from the physical toll of ageing despite Kusabue’s sprightliness or the undimmed acuity of Aiko whose only barrier to writing is that she fears she’s run out of things to say and the energy to write them. During her retirement, she remarks on the fact that her legs and back hurt while she also has a heart condition and everything just feels like too much bother. Her daughter Kyoko (Miki Maya), who lives with her along with her twenty-something daughter Momoko (Sawako Fujima), asks her why she doesn’t go out to meet a friend, but as Aiko says, most of her friends have already passed on or like her don’t really have the energy to leave the house.

In many ways, her age isolates her as she finds herself slightly at odds with the contemporary society. She turns the television up louder because she finds it difficult to understand what younger people are saying and doesn’t get why they stare at their phones all the time. Though she manages most things for herself, she has to call repair people, which costs money, if something breaks down while her daughter’s not around to fix it, even if it’s something as simple as a paper jam in a fax machine or pushing the off button on the TV too hard so it won’t turn back on again. Nevertheless, so intent is she on “enjoying” her retirement that she repeatedly turns down the entreaties of a young man from her publisher’s who wants her to write a column and always turns up with fancy sweets which are, as she says, well-considered gifts, but also a little soulless and superficial being driven by fashionable trends of which Aiko knows nothing and by which she is not really impressed.

There is something quite interesting about the contrast between herself and fifty-something Yoshikawa (Toshiaki Karasawa) who is also a man behind the times and a relic of the patriarchal culture she railed against in her writing and rejected in her personal life, divorcing two husbands and going on to raise her daughter alone. In the opening scenes, she reads an entry from an advice column about a woman who’s sick of her husband of 20 years because he’s a chauvinist who dumps all of the domestic responsibilities onto her while looking down on her because of it. Aiko tuts and contradicts the advice of the columnist, remarking that the answer is simple. She should just tell him to his face that she hates him and then leave. Nevertheless, the fact remains that not all that much has changed since she was young. The husband’s behaviour is considered “normal”, while the woman’s desire to be treated with respect or leave her marriage is not. Yoshikawa is effectively demoted because he has no idea that his treatment of a female employee amounts to workplace bullying and sexual harassment even if he didn’t intend that way because he’s trapped within this old-fashioned patriarchal ideal and is unable to see that his behaviour is not acceptable nor that he’s been taking his family for granted while considering only his own needs and positioning himself as the provider.

Yet it’s 90-year-old Aiko rather than his humiliating demotion or the failure of his marriage who begins to show him the error of his ways by accepting him into her own family like a lonely stray. Aiko’s essays don’t really say that everything was better in the past, even if she’s confused by modern people who are annoyed by the cheerful sounds of children playing and a city alive with life because she remembers how everything went quiet during the war and how depressing that could be. But she does sometimes think that progress has gone far enough and things were better when people had more time for patience with each other. That said, patience is one of the things Aiko has no time for, advising Yoshikawa to charge forward like a wild boar because one of the benefits of age is that you just don’t care anymore what anyone thinks so get ready to annoy people or exasperate them but carry on living life to the full. Ironically, that might be a gift that he gave her by convincing her to write again which returned purpose to her life and gave her a reason to engage again with the world around her lifting her depression and making her feel as if she still mattered. The real Aiko turned 100 in 2023 and carried on writing, while 90-year-old Kusakabe is herself undergoing something of a career resurgence in recent years proving that even if you’re 90 years old, so what? There’s still a lot of life left to be lived and you might as well carry on living it doing what you love for as long as you can.

90 Years Old – So What? screens 21st June as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Trailer (English subtitles)