When we say, “what goes around comes around”, we usually mean it in a bad way that someone is only getting what they deserve after behaving badly themselves. But the reverse is also true. The smallest acts of kindness people do without thinking can have quite profound effects on the world around them because, in the end, we are all connected. A bereaved father remarks that he thought novels that only had kind-hearted characters were unrealistic, but now he wants to believe that kind of world could exist after realising the impact his late daughter’s kindness had on those around her.

It was Kanami (Sawako Fujima) who saved Azusa (Haru Kuroki) in middle school when she was being bullied for coming from a single-parent family and the pair remained firm friends ever after until Kanami was suddenly killed in an accident while working overseas. Kanami’s loss leaves Azusa struggling to move forward with her life while mired in grief and uncertainty. Having lost her mother some years previously, she has never really dealt with the trauma of her parent’s acrimonious divorce and has a rather cynical view of marriage despite working as a wedding planner where her unmarried status sometimes causes her clients anxiety though it obviously has very little do with her ability to do her job. She’s always been clear with her long-time boyfriend Sumito (Aoi Nakamura) that marriage isn’t something she sees in her future, though he seems to want more commitment, while she repeatedly describes him as “unreliable” and is hesitant to take the next step with their relationship whether it involves getting married or not.

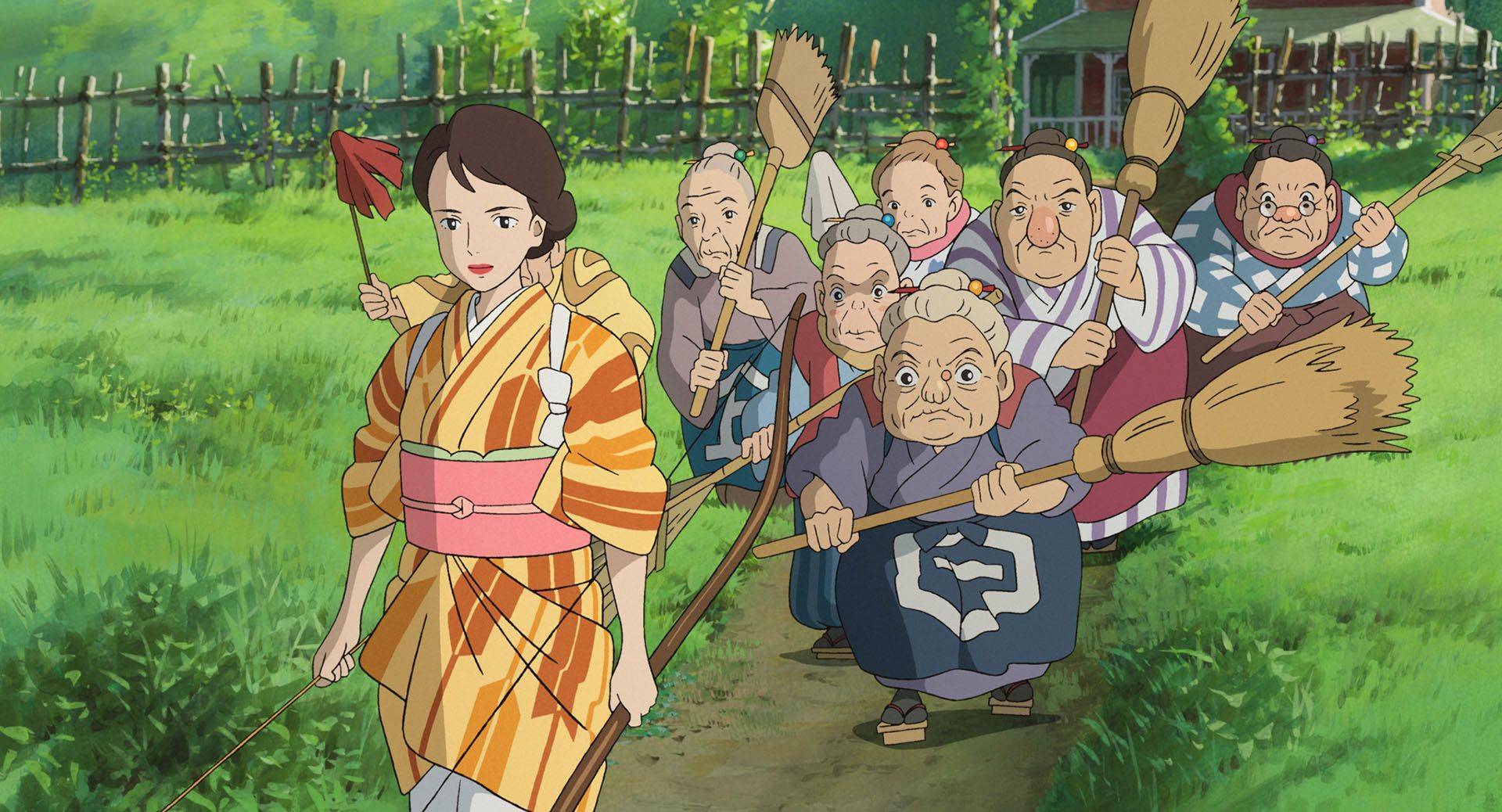

In that sense it’s really Azusa’s inability to surrender herself to the concept of what her grandmother (Jun Fubuki) calls “amai-tagai”, or mutual solidarity, which they experience first-hand while visiting her as another old lady nearby comes rushing in saying her house is on fire. It’s not so much reciprocity as a generalised idea of having each other’s backs, that people help each other as needed without keeping score in much the same way as Azusa was saved by Kanami and as she later realises by Komichi (Mitsuko Kusabue) whose piano-playing soothed her spirit though Komichi intended to play in secret, allowing her music to blend in with the six o’clock chimes as a daily act of atonement for having played the piano for boys who were going off to war many of whom never returned. It is then Azusa who saves Komichi in turn by telling her that she felt comforted by her music and that she does not believe that she has no right to play it simply because of the ways it was misused in the past.

What Azusa fears is that by getting married she would essentially be cutting herself off from her paternal grandmother who, aside from her aunt (Tamae Ando) who is also Komichi’s housekeeper, is the only other family member she seems to have a meaningful connection with. Unable to let go Kanami, she keeps sending her messages little knowing that her mother is actually reading them and feeling both sorry and grateful that her daughter had such a good friend who like her is also struggling to continue on without her. She and Kanami’s father (Tomorowo Taguchi) find solace in the letters they receive from children at an orphanage where Kanami used to donate cakes and sweets after visiting there on a job. The photos she took are on display at their bathrooms, Azusa said because Kanami wanted them to be in a place where the children felt free to embrace their feelings privately without fear of embarrassment.

The photographs, letters, and belated gifts are all examples of the ways in which what Kanami sent around is still going around and will continue to do so long after she herself is gone. Through realising the reality of “aimi-tagai”, Azusa learns that the world can also be a kind place, Sumito might be more “reliable” than she thought, and it might not be such a bad idea to trust people after all. Based on the novel by Tei Chujo, the film’s interwoven threads of serendipitous connections and the unexpected results of momentary acts of kindness prove oddly life-affirming if only in the ways in which each realise that Kanami is always with them even if physically absent.

Aimitagai screened as part of this year’s Toronto Japanese Film Festival.

Trailer (no subtitles)