A mother and daughter find themselves deceived by the same man, each hemmed in by realities which cannot be altered but eventually coming to a place of mutual understanding that allows them to restore their relationship not only as parent and child but as women in Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1954 melodrama, The Woman in the Rumour (噂の女, Uwasa no Onna). The first question we might ask ourselves is to which of the women the title refers, or indeed to which rumour, though in a sense rumours matter little for either of them when the problem is the constraints which each of them feel as women in the contemporary society.

Even so, the sense of shame is evident when Yukiko (Yoshiko Kuga) is brought back to the geisha house run by her mother Hatsuko (Kinuyo Tanaka) after having attempted to take her own life in Tokyo. As we learn, the reason for her despair is in part heartbreak. She had been engaged but her fiancé’s family convinced him to end their relationship when they discovered that her mother ran a geisha house. Thus the suicide attempt is also a reflection of her sense of futility. She will always be the daughter of a woman who earned her living in the sex trade. This is a fact that cannot be changed and may lead her to think that her situation is hopeless because the same thing is likely to happen again leaving her unable to marry in a society in which there are few options for a single woman to make a life for herself not to mention the loneliness of living without romantic love.

Hatsuko, meanwhile, is uncertain how seriously she should take the situation in part believing that it’s a product of youthful naivety in her daughter’s first romantic heartbreak. When a young doctor with whom she is close, Matoba (Tomoemon Otani), explains to her that Yukiko is depressed because she feels deep shame, self-loathing, and hopelessness due to her mother’s occupation, Hatsuko struggles to understand it and does not fully believe him. Nevertheless, she took care to bring her daughter up largely outside of the geisha world, sending Yukiko to Tokyo to study music implying that she herself to some degree sees her work as improper. The other girls view Yukiko with a degree of disdain, realising that her refinement was bought with their exploitation and noticing her animosity towards them.

Hatsuko is mother both to Yukiko and the young women under her care who are always quick to point out that this is one of the better geisha houses because they are well looked after. When one of the women, Usugumo (Kimiko Tachibana), is taken ill, Hatusko calls in the doctor and allows her time off to rest which likely would not be granted at another house. She is reluctant to send her to hospital, but would if the situation called for it. In a sense it’s this solicitation that eventually allows Yukiko to find accommodation with her mother’s profession as she grows closer to the other women while nursing Usugumo herself and comes to understand their particular circumstances that have left them no choice but to live as geisha. Usugumo is reluctant to go to hospital because she is worried about the money she’d usually send to her sister Chiyoko (Sachiko Mine) who works the family farm and cares for their sickly father, but when she dies Chiyoko herself is left with little option other than to petition the geisha house to take her sister’s place.

On seeing Chiyoko sitting on the step and pleading to be taken on, another of the women laments as she’s leaving that she wonders when there will be no more need for women like them. The geisha world is perhaps an unchangeable reality, just like Yukiko’s birth and her mother’s age. The rumours that surround Hatsuko are to do with her closeness with Matoba with whom she has clearly been in an intimate relationship, dreaming of becoming his wife and even considering selling the geisha house to buy a large property where they could live together as a couple while he runs a private clinic. Matoba predictably decides he prefers the younger Yukiko, Hatsuko increasingly desperate after overhearing their conversation about leaving her behind to move to Tokyo together where Matoba ponders finishing his education. The play they’ve gone to see almost feels like a personal attack as an actor intones that feelings of love at 20 are fine but at 60 it’s merely shameful. “Even carp know better than to fall in love at this age”, he adds, the old woman a figure of ridicule in her romantic delusion leaving Hatsuko feeling both humiliated and resentful.

When Hatsuko finally confronts Matoba, she does it as a scorned woman rather than as a mother, while Yukiko in turn first turns on her rather than Matoba even as she begins to realise the reality of the situation that the man who seduced her had been using her mother for his own gain in total disregard of her feelings. In short, even if Hatsuko were not her mother which certainly makes this a very complicated situation, he is not the sort of man she’d want to make a life with. Acutely aware of her own experiences of heartbreak, she fears for her mother’s wellbeing and comes to an understanding of her as a woman while accepting that “men are all alike” and in that at least perhaps her mother’s profession is the most honest of all. Mutually betrayed, mother and daughter are able to repair their familial bonds while Yukiko finds herself taking refuge in the geisha house as a space of female solidarity and bulwark against a cruel and patriarchal society.

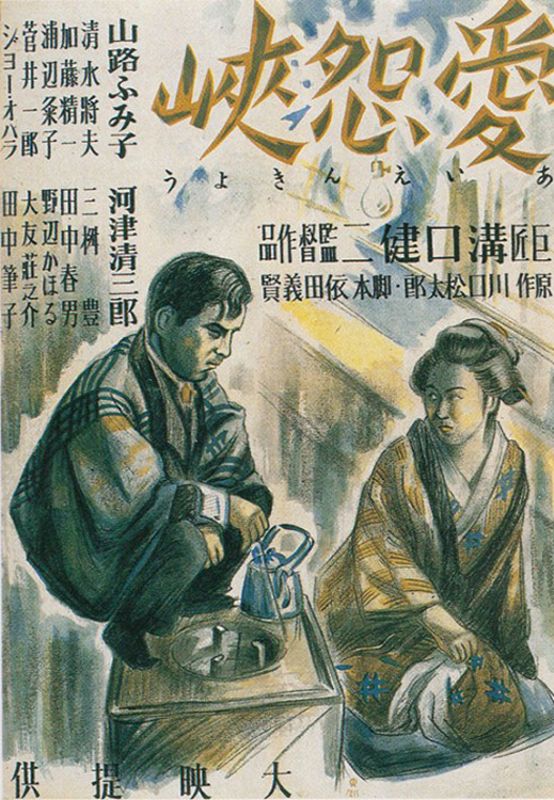

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,