Takahiro Miki has made a name for himself as a purveyor of sad romances. Often his protagonists are divided by conflicting timelines, social taboos, or some other fantastical circumstance, though Drawing Closer (余命一年の僕が、余命半年の君と出会った話。, Yomei Ichinen no Boku ga, Yomei Hantoshi no Kimi to Deatta Hanashi) quite clearly harks back to the jun-ai or “pure love” boom in its focus on young love and terminal illness. Based on the novel by Ao Morita, the film nevertheless succumbs to some of genres most problematic tendencies as the heroine essentially becomes little more than a means for the hero’s path towards finding purpose in life.

17-year-old Akito (Ren Nagase) is told that he has a tumour on his heart and only a year at most to live. Though he begins to feel as if his life is pointless, he finds new strength after running into Haruna (Natsuki Deguchi) who has only six months yet to him seems full of life. Later, Haruna says he was actually wrong and she felt completely hopeless too so actually she really wanted to die right away rather than pointlessly hang round for another six months with nothing to do and no one to talk to. But in any case, Akito decides that he’s going to make his remaining life’s purpose making Haruna happy which admittedly he does actually do by visiting her every day and bringing flowers once a week.

But outside of that, we never really hear that much from Haruna other than when she’s telling Akito something inspirational and he seems to more or less fill in the blanks on his own. Thus he makes what could have been a fairly rash and disastrous decision to bring a former friend, Ayaka (Mayuu Yokota), with whom Haruna had fallen out after the middle-school graduation ceremony that she was unable to go to because of her illness. Luckily he had correctly deduced that Haruna pushed her friend away because she thought their friendship was holding her back and Ayaka should be free to embrace her high school life making new friends who can do all the regular teenage things like going to karaoke or hanging out at the mall. Akito is doing something similar by not telling his other friends that he’s ill while also keeping it from Haruna in the hope that they can just be normal teens without the baggage of their illnesses.

The film never shies away from the isolating qualities of what it’s like to live with a serious health condition. Both teens just want to be treated normally while others often pull away from them or are overly solicitous after finding out that they’re ill but at the same time, it’s all life lessons for Akito rather a genuine expression of Haruna’s feelings. We only experience them as he experiences them and so really she’s denied any opportunity to express herself authentically. Rather tritely, it’s she who teaches Akito how to live again in urging him that he should hang in there and continue to pursue his artistic dreams on behalf of them both. Meanwhile, she encourages him to pursue a romantic relationship with Ayaka, in that way ensuring that neither of them will be lonely when she’s gone and pushing them towards enjoying life to its fullest.

Nevertheless, due to its unbalanced quality and general earnestness the film never really achieves the kind of emotional impact that it’s aiming for nor the sense of poignancy familiar from Miki’s other work. Perhaps taking its cues from similarly themed television drama, the production values are on the lower side and Miki’s visual flair is largely absent though this perhaps helps to express a sense of hopelessness only broken by beautiful colours of Haruna’s artwork. Haruna had used drawing as means of escaping from the reality of her condition, but in the end even this becomes about Akito with her mother declaring that in the end she drew for him rather than for herself. Even so, there is something uplifting in Akito’s rediscovery of art as a purpose for life that convinces him that his remaining time isn’t meaningless while also allowing him to discover the desire to live even if his time is running out.

Trailer (English subtitles)

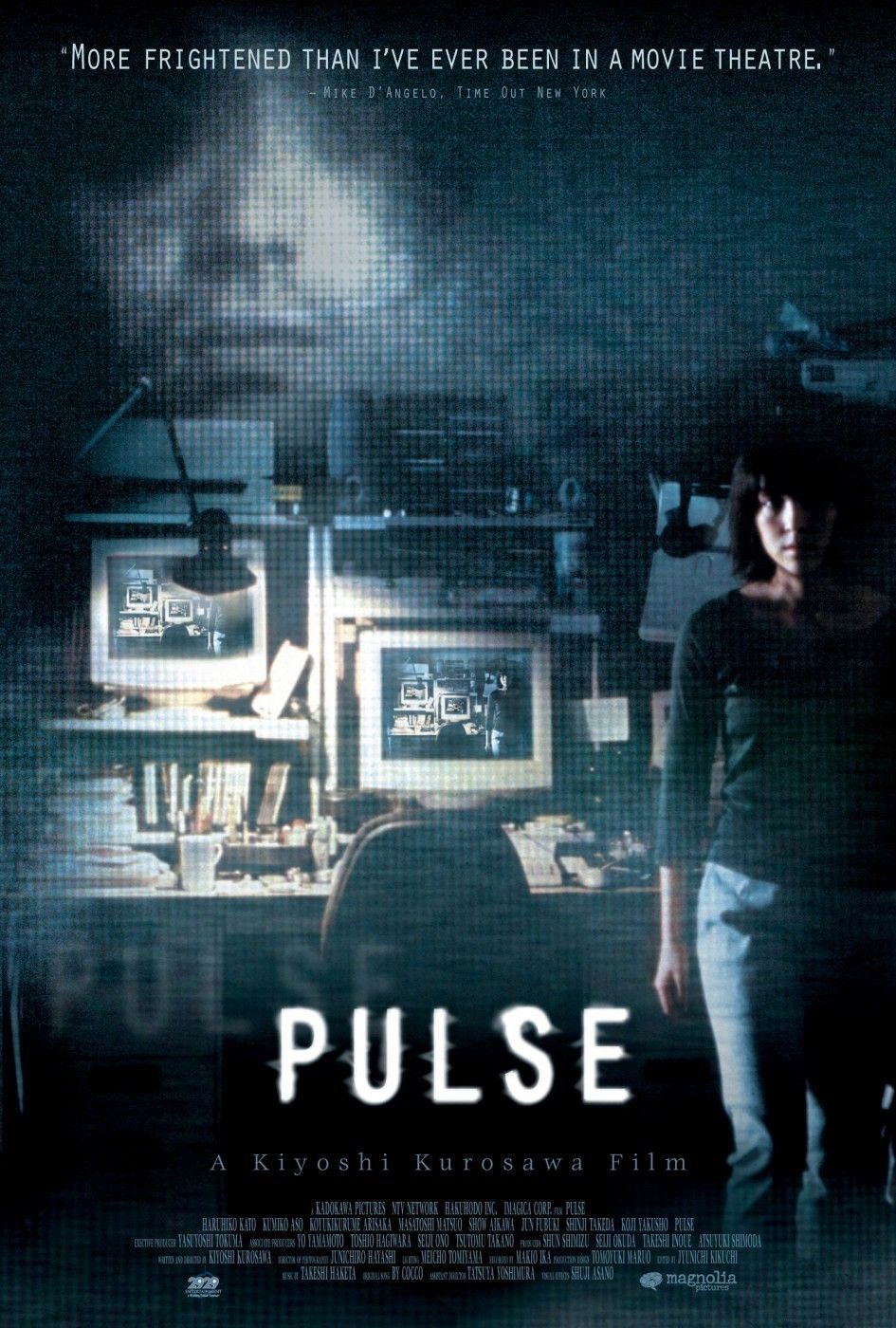

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence. You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.

You know how it is, you’ve left college and got yourself a pretty good job (that you don’t like very much but it pays the bills) and even a steady girlfriend too (not sure if you like her that much either) but somehow everything starts to feel vaguely dissatisfying. This is where we find Kenji (Ryo Kase) at the beginning of Isao Yukisada’s sewing bee of a movie, Rock ’n’ Roll Mishin (ロックンロールミシン). However, this is not exactly the story of a salaryman risking all and becoming a great artist so much as a man taking a brief bohemian holiday from a humdrum everyday existence.