Cinema of the immediate post-war period generally leaned towards upbeat positivity, insisting that, yes, the situation is painful and difficult but it wouldn’t always be this way, at least as long as ordinary people kept their chins up and worked hard to build a better future. Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night (夜の女たち, Yoru no Onnatachi) is very much not interested in this rosy vision of future success being sold by a new morale boosting propaganda machine, but in laying bare the harsh and unforgiving nature of a society that was fast preparing to leave a significant part of its population far behind. Women suffer in war, but they suffer after war too – particularly in a society as stratified as Japan’s had been in which those left without familial support found themselves entirely excluded from the mainstream world.

Cinema of the immediate post-war period generally leaned towards upbeat positivity, insisting that, yes, the situation is painful and difficult but it wouldn’t always be this way, at least as long as ordinary people kept their chins up and worked hard to build a better future. Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night (夜の女たち, Yoru no Onnatachi) is very much not interested in this rosy vision of future success being sold by a new morale boosting propaganda machine, but in laying bare the harsh and unforgiving nature of a society that was fast preparing to leave a significant part of its population far behind. Women suffer in war, but they suffer after war too – particularly in a society as stratified as Japan’s had been in which those left without familial support found themselves entirely excluded from the mainstream world.

Fusako (Kinuyo Tanaka), a noble, naive woman still hasn’t heard from her presumably demobbed husband and is living with her in-laws. Her young son has tuberculosis and she is desperately short of money. Selling one of her kimonos, Fusako is excited to to hear of an “interesting proposition” but is repulsed when she realises the saleswoman is inciting her to an act of prostitution. After all, she says, everybody is doing it.

After undergoing a series of tragedies, Fusako thinks things are beginning to go right for her when she manages to get a secretarial job through the kindness of a connection, but it turns out that Mr. Kuriyama (Mitsuo Nagata) is not all he seems and his business may not be as legitimate as Fusako believed it to be. Another small miracle occurs on a street corner as Fusako runs into her long lost sister, Natsuko (Sanae Takasugi), formerly living in Korea and now repatriated to Japan, but a return to normal family life seems impossible in the still smouldering ruins of Osaka filled with black marketeering, desperation, and hopelessness.

Inspired by the Italian Neo Realist movement, Mizoguchi makes brief use of location shooting to emphasise the current state of the city, still strewn with rubble and the aftermath of destruction. Osaka, like Natsuko and Fusako, finds itself at a cross roads of modernity, paralysed by indecision in looking for a way forward. Fusako, the kinder, more innocent sister dresses in kimono, does not smoke, and is committed to working hard to build a new life for herself. Natsuko, by contrast, dresses exclusively in Western clothing, smokes, drinks, and works as a hostess at a dancehall with the implication that she is already involved in casual forms of prostitution.

Natsuko’s way of life, and later that of Fusako’s much younger sister-in-law Kumiko (Tomie Tsunoda), is painted as a direct consequence of an act of sexual violence. Having been raped during the evacuation from Korea, Natsuko feels herself to have been somehow defiled and rendered unfit for a “normal” life, relegated to the underground world of the sex trade as an already damaged woman. Fusako disapproves of her sister’s choices and is alarmed by the unfamiliar world of bars and dance halls but eventually ends up in the world of prostitution herself as a result of emotional violence in the form of cruel yet incidental betrayal. Fusako’s “descent” into prostitution is less survival than an act both of revenge and of intense self-harm as she vows to avenge herself on the world of men through spreading venereal disease.

Mizoguchi’s attitudes towards sex work were always complex – despite displaying sympathy for women who found themselves trapped within red light district as his own sister had been, he was also a man who spent much of his life in the company of geishas. Nevertheless Women of the Night veers between empathy and disdain for the hosts of post-war “pan pans” existing in codependent female gangs in which violence and hierarchy were as much an essential part as mutual support. The film opens with a sign which instructs women that they should not be seen out after dark lest they will be taken for prostitutes, respectable women should make a point of being home at the proper hour. Later, when Fusako is picked up by a police raid, she comes across a woman from the “purity board” who wants to hand out some pamphlets to help women “reform” from their “impure” ways and temper their presumably insatiable sexual desire. Fusako quite rightly tells the woman where to go while the others echo her in confirming no one has volunteered to live this way because they like it. Starving to death with a pure heart is one thing, but what are any of these women supposed to do in a world that refuses them regular work when they have already lost friends and family and are entirely alone with no hope of survival?

A third option exists in the form of a home for women which has been set up for the express purpose of “reforming” former prostitutes so that they can lead “normal” lives. The home provides ample meals, medical treatment and work though its attitude can be slightly patronising even in its well meaning attempt to re-educate. Again the home is working towards an ideal which is not evident in reality – there are no jobs for these women to go to, and no husbands waiting to support them. Incurring yet another tragedy, Fusako receives a well meaning lecture from a male employee at the home to the effect that it’s time for women to work together to build a better world for all womankind but Fusako has seen enough of the sisterhood realise that won’t save her either and leaves the man to his platitudes trailing a dense cloud of contempt behind her.

Yet Fusako does change her mind, finally reunited with the missing Kumiko who has also fallen into prostitution after running away from home and being tricked by a boy who pretended to be nice but only ever planned to rob and rape her. In a furious scene of maternal rage, Fusako rails against her plight, enraged by Kumiko’s degradation which ultimately forces her to see her own. Brutally beaten by the other women for the mere suggestion of leaving the gang, Fusako is held, Christ-like, while she pleads for an end to this existence, that there should be no more women like these. The storm breaks and the other women gradually come over to Fusako’s side, depressed and demoralised, left with no clear direction to turn for salvation. Mizoguchi ends on a bleak note of eternal suffering and continuing impossibility but he pauses briefly to pan up to an unbroken stained glass window featuring the Madonna and child. Fusako emerges unbroken, taking Kumiko under her maternal wing, but the future they walk out into is anything but certain and their journey far from over.

Screened at BFI as part of the Women in Japanese Melodrama season. Screening again on 21st October, 17.10.

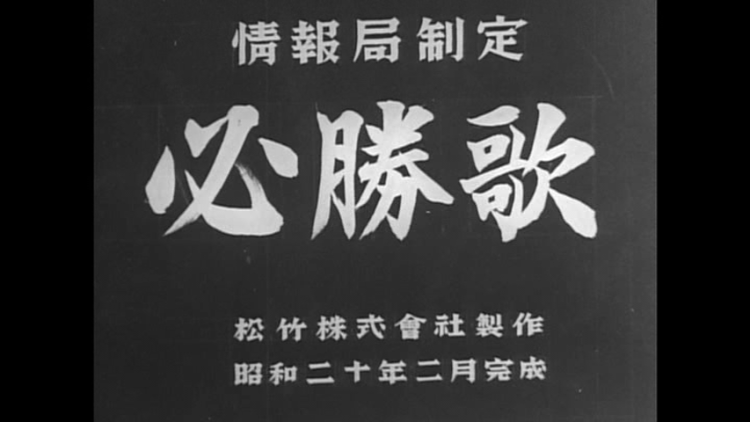

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles.

Completed in 1945, Victory Song (必勝歌, Hisshoka) is a strangely optimistic title for this full on propaganda effort intended to show how ordinary people were still working hard for the Emperor and refusing to read the writing on the wall. Like all propaganda films it is supposed to reinforce the views of the ruling regime, encourage conformity, and raise morale yet there are also tiny background hints of ongoing suffering which must be endured. Composed of 13 parts, Victory Song pictures the lives of ordinary people from all walks of life though all, of course, in some way connected with the military or the war effort more generally. Seven directors worked on the film – Masahiro Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Hiroshi Shimizu, Tomotaka Tasaka, Tatsuo Osone, Koichi Takagi, and Tetsuo Ichikawa, and it appears to have been a speedy production, made for little money though starring some of the studio’s biggest stars in smallish roles. Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old.

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old. Perhaps oddly for a director of his generation, Kon Ichikawa is not particularly known for family drama yet his 1960 effort, Her Brother (おとうと, Ototo), draws strongly on this genre albeit with Ichikawa’s trademark irony. A Taisho era tale based on an autobiographically inspired novel by Aya Koda, Her Brother is the story of a sister’s unconditional love but also of a woman who is, in some ways, forced to sacrifice herself for her family precisely because of their ongoing emotional neglect.

Perhaps oddly for a director of his generation, Kon Ichikawa is not particularly known for family drama yet his 1960 effort, Her Brother (おとうと, Ototo), draws strongly on this genre albeit with Ichikawa’s trademark irony. A Taisho era tale based on an autobiographically inspired novel by Aya Koda, Her Brother is the story of a sister’s unconditional love but also of a woman who is, in some ways, forced to sacrifice herself for her family precisely because of their ongoing emotional neglect. Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself.

Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself.

Kinuyo Tanaka was one of the most successful actresses of the pre-war years well known for her work with celebrated director Kenji Mizoguchi including several of his most critically acclaimed works such as Sansho the Bailiff, Ugetsu, and The Life of Oharu. However, post-war Japan was a very different place and Tanaka had a different kind of ambition. With 1953’s Love Letter (恋文, Koibumi) she became Japan’s second ever female feature film director, though her working and personal relationship with Mizoguchi ended when he attempted to block her access to the Director’s Guild of Japan. No one quite knows why he did this and he tried to go back on it later but the damage was done, Tanaka never forgave him for this very public betrayal. Whatever Mizoguchi may have been thinking, he was very wrong indeed – Tanaka’s first venture behind the camera is an extraordinarily interesting one which is not only a technically solid production but actively seeks a new kind of Japanese cinema.

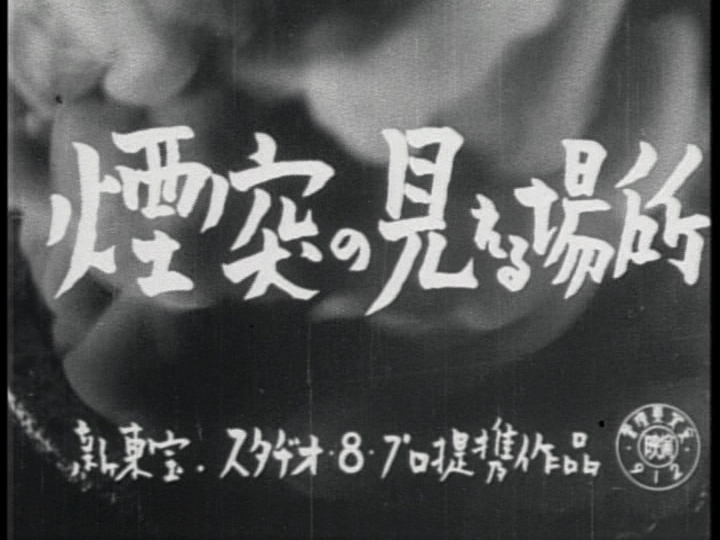

Kinuyo Tanaka was one of the most successful actresses of the pre-war years well known for her work with celebrated director Kenji Mizoguchi including several of his most critically acclaimed works such as Sansho the Bailiff, Ugetsu, and The Life of Oharu. However, post-war Japan was a very different place and Tanaka had a different kind of ambition. With 1953’s Love Letter (恋文, Koibumi) she became Japan’s second ever female feature film director, though her working and personal relationship with Mizoguchi ended when he attempted to block her access to the Director’s Guild of Japan. No one quite knows why he did this and he tried to go back on it later but the damage was done, Tanaka never forgave him for this very public betrayal. Whatever Mizoguchi may have been thinking, he was very wrong indeed – Tanaka’s first venture behind the camera is an extraordinarily interesting one which is not only a technically solid production but actively seeks a new kind of Japanese cinema. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.