The Zero Fighter has taken on a kind of mythic existence in a romanticised vision of warfare, yet as Toshio Masuda’s Zero (零戦燃ゆ零戦燃ゆ, Zerosen moyu) implies its time in the spotlight was in fact comparatively short. Soon eclipsed by sleeker planes flown by foreign pilots, the Zero’s glory faded until these once unbeatable fighters were relegated to suicide missions. On one level, the film uses the Zero as a metaphor for national hubris, a plane that ironically flew too close to the sun, but on another can never overcome the simple fact that this marvel of engineering was also a tool of war and destruction.

The film is loosely framed around two members of Japan’s Imperial Navy, Hamada (Daijiro Tsutsumi) and Mizushima (Kunio Mizushima), who as cadets consider deserting to escape the brutality of Navy discipline. Having left the base they’re accosted by an inspirational captain who talks them out of leaving by showing them a prototype model of the Zero and convincing them they only need to stick it out for a few more years in order to get the opportunity to fly one. Mizushima, the film’s narrator, doesn’t qualify as a pilot and is related to the ground crew while Hamada does indeed get to pilot a Zero fighter and becomes one of the top pilots in the service.

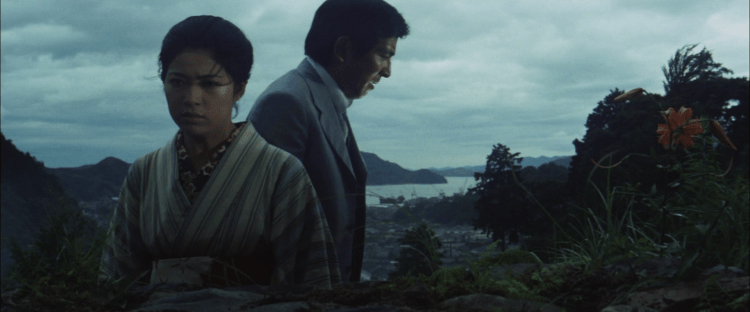

The viewpoint is is then split between the view from the ground and that from the clouds. Mizushima makes occasionally surprising statements such as candidly telling love interest Shizuko (Yû Hayami) that they are unlikely to win the war, while becoming ever more concerned for Hamada at one point telling him there’s a problem with his plane in the hope that he won’t take off that day. Hamada meanwhile is completely taken over by the spirit of the Zero and even when given a chance to escape the war after being badly injured, chooses to return because he does not know what else to do. When he visits home after leaving hospital, no one is there. His mother eventually arrives and explains that the family has become scattered with his siblings seconded to the war effort in various places throughout the country.

Hamada’s dedication and personal sacrifice are in some senses held up as the embodiment of the Zero. The reason for its success is revealed to lie in the decision to remove the armouring for the cockpit leaving the pilot’s life unprotected, something which the American engineers describe as unthinkable. In an early meeting, a superior officer complains that they’re losing too many pilots and need to reinstall some of the armouring, but finds little support. Not only this is a cold and inhuman decision, but it’s poor economic sense given that skilled pilots are incredibly valuable and in short supply. After all, you can’t just make more. If you start from scratch you’ll need to wait 20 years and then teach them fly, but it’s a lesson the Navy never learns that is only exacerbated with the expansion of the kamikaze squads which squander both men and pilots for comparatively little gain.

These “philosophical differences” are embodied in the nature of the Zero which is configured to be nimble and outmanoeuvre the enemy but is quickly eclipsed not least when foreign powers figure out the way to beat it lies in numbers in which they have the advantage. There is something of a post-Meiji spirit in the feeling that Japan is lagging behind Western powers and desperately needs to develop its own military tech in order to defend itself. On hearing rumours of the Zero fighter, MacArthur scoffs and says that Japan can’t even build cars so he doesn’t believe they could design a plane that could fly such large distances while others suggest that they will still need the element of surprise if they ever go to war with America because its technology is still superior.

Walking a fine line, the film tries to avoid glorifying “war”, but it cannot always help indulging in nationalist fantasy such as in its statement that thanks to the Zero “the Japanese flag covered a vast area of the Pacific” in the wake of Pearl Harbour. These may be fantastically well designed machines that were incredibly good at what they were created to do, only what they were created to do was kill and destroy. The plane’s fortunes and Japan’s are intrinsically linked, the sense of superiority in the air lasts only a short time before Western technological advances over take it and the war continues to go badly. The film dramatises the tragedy of war through the friendship between the two men which eventually causes Mizushima to sacrifice his love for Shizuko by convincing her marry Hamada hoping that his priorities would change and he’d decide to take a position as an instructor rather than heading back to the front.

For her part, it seems that Shizuko was also in love with Mizushima, but also caught in a moment of confusion between love and patriotism that encourages her to think she should do as Mizushima says and embrace this man who has dedicated his life to his country. In the end, it buys them each loss and misery, but also a moment of transcendent hope even if it was based on a falsehood in the pleasant memory that Mizushima gives Hamada of the life he is giving up by rejecting it to return to the front. For Mizushima, Hamada and the Zero may become one and the same. At the end of the war he can’t bear to see the remaining Zero’s sold for scrap and asked to be “gifted” one as the Captain who’d first shown one to him said he would be, so that he can give it a proper a “funeral”, or perhaps send it to Hamada in the afterlife after he is killed mere days before the surrender. Masuda cannot help romanticising the wartime conflict with his dashing pilots and their thrilling dogfights, often depicting it more as a kind of game than an ugly struggle of death and destruction, but does lend a note of poignancy to his tale of lives thwarted by the folly of war.

Trailer (no subtitles)

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best.

And so, the saga finally reaches its conclusion. Final Episode (仁義なき戦い: 完結篇, Jingi Naki Tatakai: Kanketsu-hen) brings us ever closer to the contemporary era and picks up in the mid ‘60s where Hirono is still in prison and Takeda, released on a technicality, has decided to move the yakuza into the legit arena. The surviving gangs have united and rebranded themselves as a political group known as the Tensei Coalition. However, not everyone has joined the new gangsters’ union and the enterprise is fragile at best. If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of

If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of