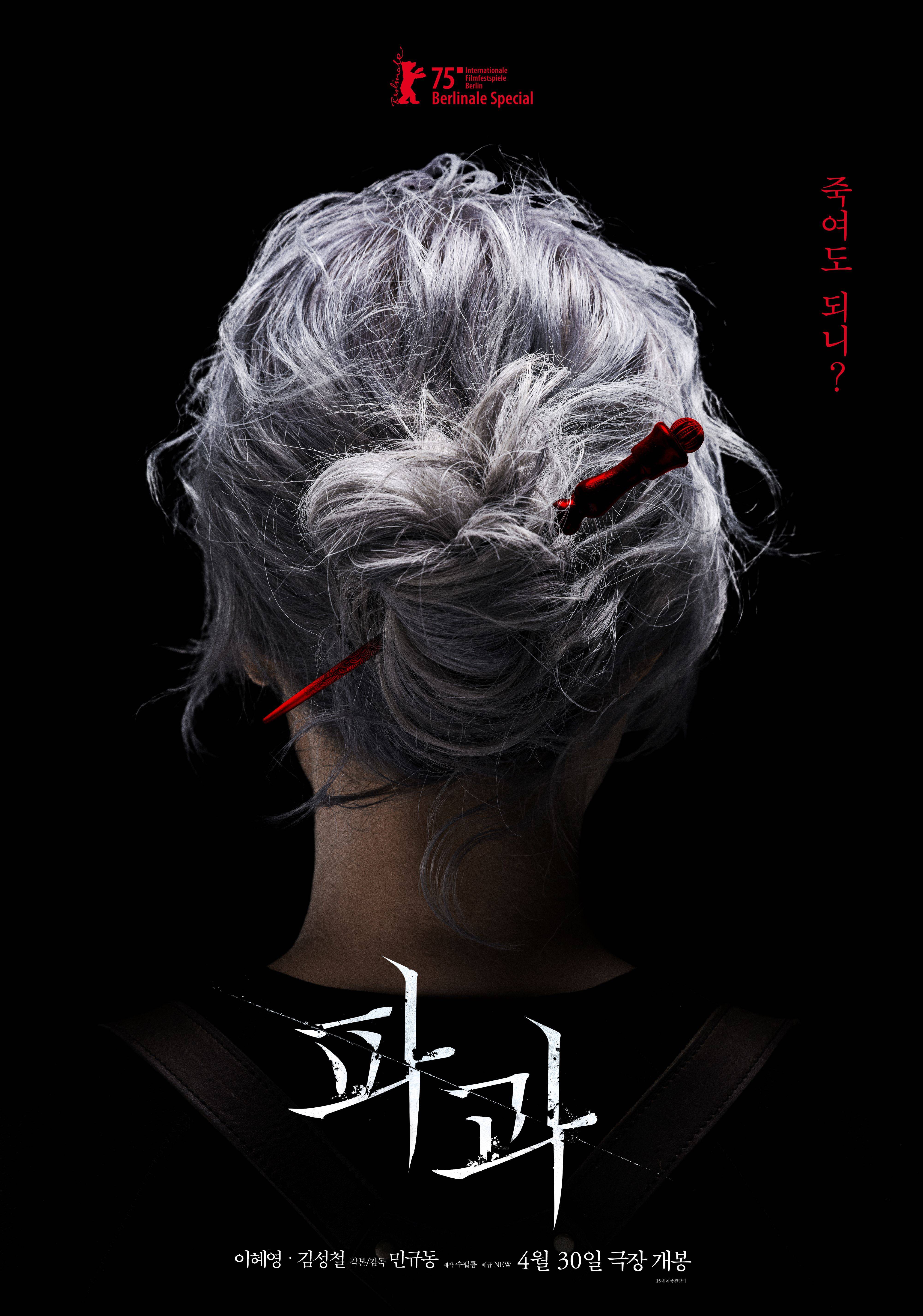

There’s an acute vulnerability that comes with ageing. It’s not vanity or mortality so much as your body betraying you as even once simple tasks become increasingly more difficult. When you’re an assassin, a loss of speed or dexterity is cause for concern and Hornclaw (Lee Hye-young) is beginning to feel her age. Her hands have begun to shake uncontrollably and as she admits to a stray dog she finds herself taking in, you forget things when you’re old. There are those in the office who have begun to notice that Hornclaw is not quite as she was and view her as a thorn in their side, a relic of an earlier era preventing them from moving on into a hyper-capitalistic future.

The original Korean title of Min Kyu-dong’s The Old Woman with the Knife (파과 Pagwa) is “bruised fruit”. An old woman working at a greengrocers throws in an extra peach for free because it’s damaged and people won’t buy them, which is silly, in her view, because they’re the best ones and always taste the sweetest. On that level, the film is about ageism and the ways older people are often written off as past their prime, but on another also about Hornclaw’s bruised but not quite buried heart and the hidden empathy that defines her life even as a contract killer. It may also in its way refer to her opposite number, Bullfight (Kim Sung-cheol), a hotshot young assassin recruited by her less ethically minded boss Sohn (Kim Kang-woo) who despite his sadistic cruelty is really just a hurt little boy looking for a maternal figure in the legend that surrounds Hornclaw.

She was a stray dog herself until someone took her in and gave her a home, much as Bullfight is now looking for a place to belong. Hornclaw comes to identify with the dog she rescues, Braveheart, because as the vet says it’s awful to be abandoned when you’re old and sick, but perhaps also when you’re young and lonely. As her mentor taught her, having something to protect also makes you vulnerable while as you age the people you’ve lost return. Like her underling Gadget who sees visions of his late daughter, Hornclaw too is drawn back towards the past in seeing echoes of Ryu (Kim Mu-yeol), the man who saved her, in altruistic vet Dr Kang (Yeon Woo-jin).

There may be something disingenuous in the insistence that each of us must save the world coming from a band of supposedly ethical hitmen who only knock off “bugs” that are actively harmful for society. After all, who is making those decisions as to what constitutes “harmfulness”? Everyone Hornclaw takes out is indeed morally indefensible, but as she cautions Bullfight, when you start seeing people as insects you become an insect yourself. Sohn wants to reform the agency to take on more lucrative contract killing jobs such as taking out a wealthy man whose only crime appears to be being a cheating louse, while Hornclaw insists on sticking to their principles and only carrying out missions of justice which are the cases Sohn keeps turning down like that of a religious leader who has been abusing his followers.

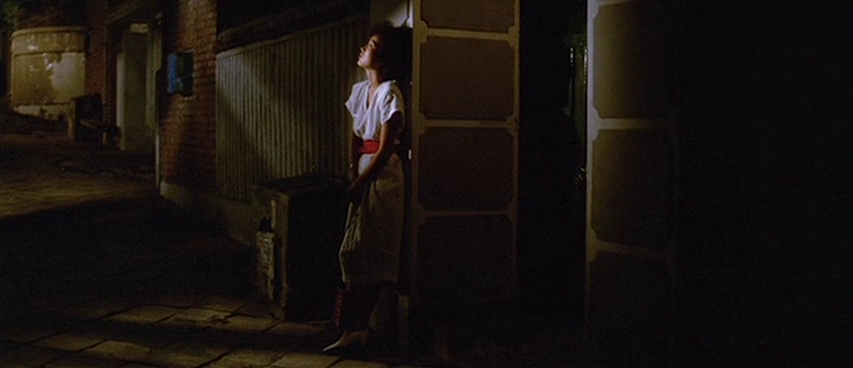

The vision of Hornclaw as a resentful avenger echoes that of Meiko Kaji in the Female Prisoner Scorpion series. Often caught in silhouette, she too wears a wide-brimmed hat that hides her eyes and aids anonymity, while she at one point gives her real name as “Seol-hwa” which means “snow flower” and hints at Lady Snowblood but also to her own moment of rebirth after being discovered half-dead in the snow and rescued by Ryu who gave her a purpose and sense of self-worth, not to mention a home. The irony is that Hornclaw ends up creating a monster because of her own repressed emotionality and is then unable to understand why this figure from the past has returned to her because her way of seeing the world only allows her to interpret it in terms of vengeance.

But what her new mission tells her is that having something to protect is in many ways the point and the very thing that gives her an edge over those who have nothing left to lose. Wresting back control over the agency, she vows to continue their mission as it’s always been rather than allow Sohn’s amoral capitalism to win out over justice and righteousness. Truth be told, the superhuman quality of Hornclaw’s movements is slightly at odds with the otherwise realistic tone of the rest of the film in which, as the secretary puts it, the weight of all the years is beginning to take its toll. But ironically it’s in closing her escape route that she finds true liberation in putting her ideas into practice in a more direct way while opening herself up to the world around her. There’s still life in the woman with the knife yet, and there are still plenty of bad guys out there along with a stack of files in need of attention, which is all to say retirement is going to have to wait.

International trailer (English subtitles)