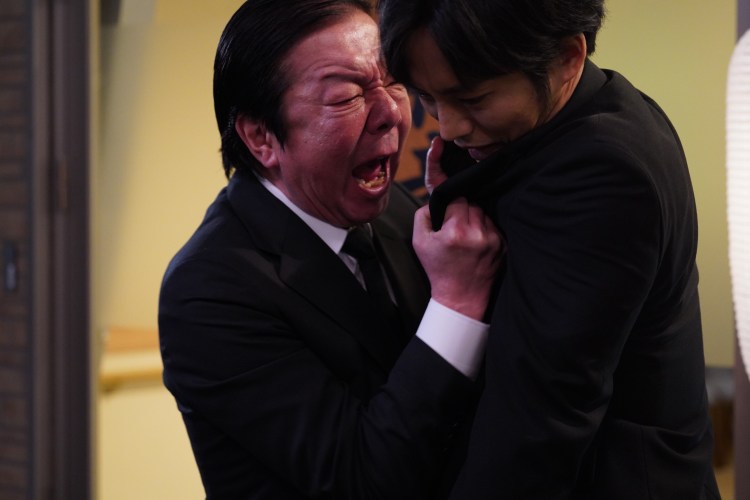

“He’s horny and looks like a fool but you can count on him” according to top mob boss Todoroki and it’s as good a description as any of the hero of Takashi Miike’s adaptation of the manga by Noboru Takahashi, The Mole Song: Undercover Agent Reiji. Billed as the conclusion of the trilogy each of which is scripted by Kankuro Kudo, The Mole Song: FINAL (土竜の唄 FINAL, Mogura no uta Final) arrives almost 10 years since the series’ first instalment and five years after the second as Reiji (Toma Ikuta) proceeds towards his ultimate target and staves off the next evolution of organised crime.

To rewind a little, as film frequently does in flashbacks to the earlier movies, Reiji was a useless street cop facing a host of complaints not least for being a bit of a creep upskirting the local ladies until offered the opportunity to go undercover in the yakuza in order to break a drug smuggling ring run by ageing boss Todoroki (Koichi Iwaki). No longer technically a law enforcement officer because undercover operations are apparently illegal in Japan, Reiji has begun to find himself torn between his ultimate mission and the codes of gangsterdom not least in his relationship with sympathetic, old school yakuza Papillon (Shinichi Tsutsumi) so named for his love of butterflies many of which adorn his brightly coloured suits.

Reiji’s inner conflict may ironically mirror the giri/ninjo push and pull central to the yakuza drama as he begins to realise that in completing his mission of taking down Todoroki he will end up betraying Papillon who once saved his life at the cost of his legs. Papillon meanwhile is presented as the idealised figure of the traditional yakuza in his fierce opposition to the drugs trade in the conviction that all they do is make people’s lives miserable and destroy families. He alone maintains the traditional ideas of brotherhood that underpin the underworld society in which a boss is also a father and betrayal is a spiritual if also in a sense literal act of suicide. His opposite number, meanwhile, Todoroki’s son Leo (Ryohei Suzuki), is the evolution of the post-Bubble yakuza, highly corporatised and essentially amoral. Papillon compares him to a mutant butterfly fed on coca lives that will eventually kill all of those with which it is confined while Leo himself claims that he intends to redefine the concept of the yakuza for the new generation.

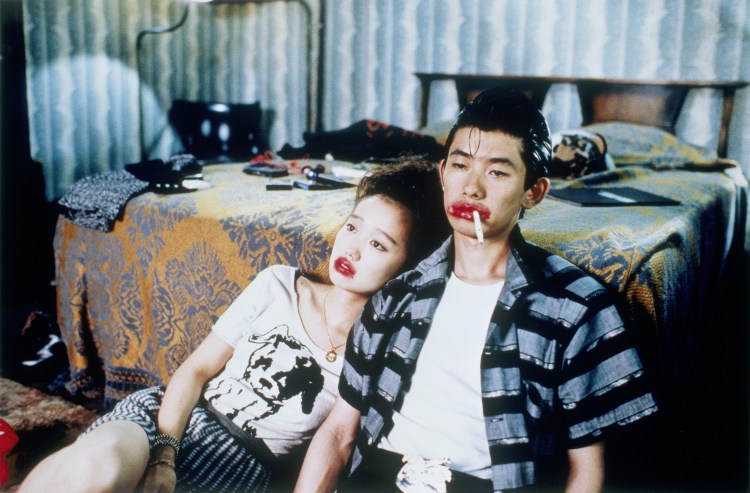

Caught between policeman and gangster, Reiji’s identity confusion is mediated through his relationships with Papillon on the one hand and pure-hearted love interest Junna (Riisa Naka) on the other. Each of them at one point tells Reiji that he is dead to them, thereby exiling him to the other side temporarily or otherwise. His yakuza traits which include the perversity which plagued him before endanger his otherwise innocent love for Junna in his inability to control his impulses, upsetting her by revealing a possible fling with a local woman while working on the drug deal in Italy, while his inclination towards police work that informs his sense of “justice” places him at odds with Papillon even though they are in many ways pursuing the same goal in keeping Japan free of dangerous drugs and the crime at surrounds them while purifying the contemporary yakuza of the pollution they have caused and restoring it to the pure ideal of another kind of “justice” advocated by Papillon which Todoroki has in a sense betrayed.

As the film makes clear, the traditional yakuza is in any case on its way out with successive law enforcement initiatives that perhaps unfairly in some senses prevent them from living their lives. Todoroki’s guys defend their choices to the more idealistic Papillon under the rationale that they can’t open bank accounts, rent apartments, or even make sure their kids have lunch to take to school, so they have to dirty their hands with these less honourable kinds of work. Leo is simply a turbo charged version of their determination to survive. As eccentric cat-like gangster Nekozawa (Takashi Okamura), making a shock reappearance, explains it isn’t as if they can go straight either because who’s going to hire a former yakuza for a regular job?

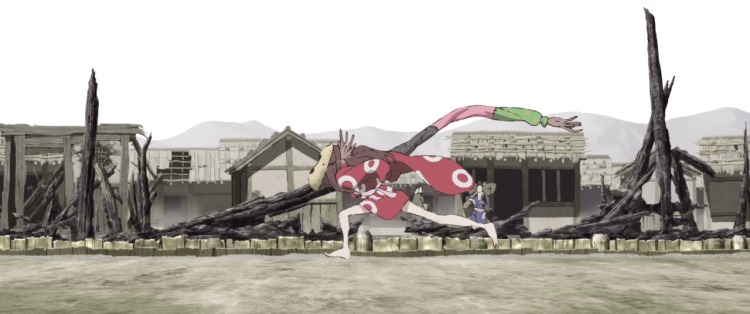

There may be in a sense a sympathy for those caught out by their choices with no real way back, a more liberal view of “justice” leaning either towards that by their own code or a simple rejection of the amoral selfishness of those who think nothing of ruining the lives of others for their own gain. With plenty of call backs to earlier instalments, Reiji once again opening the film buck naked with in this case a vase for modesty, Miike maintains the same slapstick sense of humour frequently employing zany animation and even a puppet show to express Reiji’s sometimes simplistic way of thinking. The film even unexpectedly shifts into tokusatsu in its closing sequence, bearing out the similarity in the titular “mole song” to the classic Mothra refrain, while placing Reiji and Papillon back into their respective roles having perhaps exchanged something between them in continuing to pursue their shared goal of a drug-free society.

The Mole Song: Final streamed as part of this year’s Nippon Connection.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Images: Ⓒ2021 FUJI TELEVISION NETWORK/SHOGAKUKAN/JSTORM/TOHO/OLM ⒸNOBORU TAKAHASHI/SHOGAKUKAN