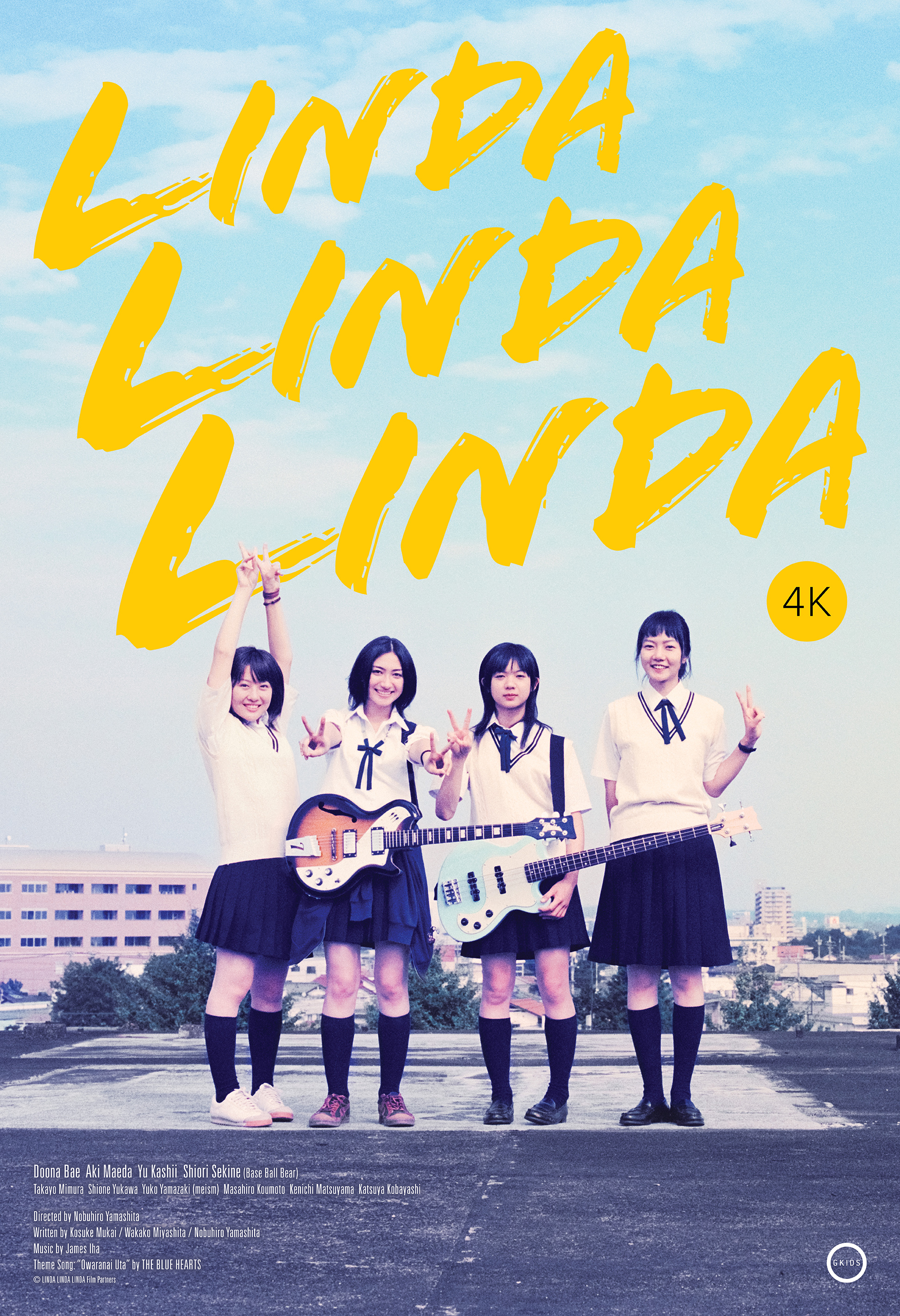

“We’ve only got a little more time to be the real us,” according to a young woman making a promo video for the upcoming school festival, but who really is the “real us”? Now celebrating its 20th anniversary, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s wistful high school dramedy Linda, Linda, Linda (リンダ リンダ リンダ) is in many ways about the process of coming into being along with the anxieties of what comes next. “We won’t end here,” the girl later adds, “We won’t let our high school days become a memory,” yet they already are in a kind of contemporaneous nostalgia and elegy for idealised youth.

Or at least, there’s already a kind of reaching back taking place as the tracks the girls pick for a replacement act are by The Blue Hearts, a 1980s punk band that has become a kind of cultural touchstone echoing a sense of youthful alienation and rebellion. “Linda Linda” is the kind of song everyone knows, and even if for some reason they don’t or don’t even speak Japanese, can at least join in with the riotous chorus. It’s this sense of universality that eventually gives it its power as torrential rain brings the entire school inside just in time to see the girls’ belated act and find themselves captivated by its infectious energy and an identification with their own sense of insecure anxiety.

It’s also the serendipitous rain that allows lonely songstress Takako an opportunity to perform having previously declined to do because it’s no fun playing on your own and all her former bandmates graduated the previous year. Moe, the girl who broke her fingers playing basketball in PE leaving the original band members unable to take the to the stage, also gets an opportunity to sing having otherwise been denied a moment of closure in being prevented from taking part in her final school festival. While Moe feels intensely guilty about rendering all their time spent rehearsing somewhat pointless, it’s really the drama between founding members Kei and Rinko that leads to the band’s demise in Rinko’s conviction that it’s “meaningless” to continue while the others decide to go ahead anyway asking Korean exchange student Son (Bae Doona) to be their vocalist because she just happened to come down the stairs at the right moment and said yes because she didn’t really understand what they were saying.

Prior to her involvement with the band, Son had been a rather isolated figure trapped in the “Japan-Korea Culture Exchange Exhibit” which seems to have been more her teacher’s idea than her own and in any case gets no actual visitors. Her Japanese is a bit limited and most of her interactions are with a little girl who lends her manga to help her learn quickly, but becoming part of the band allows her to find her voice both literally and figuratively in taking the lead as the vocalist. A boy who claims to have fallen in love with her (Kenichi Matsuyama) goes to the trouble of learning a long speech in Korean to convey his feelings, yet a bemused Son replies to him in Japanese that she’s pretty indifferent to his existence before switching to Korean to explain that she’s leaving because she’d rather be hanging out with her friends with an expression that implies she’s only just realised that’s what they are. By contrast, she has a bilingual conversation with guitarist Kei (Yu Kashii) in which they seem to understand each other perfectly and each express how glad they are that they got to be in the band together.

Similarly, it’s the concert itself that seems to heal rifts with a simple “Are you alright?” from Rinko (Takayo Mimura) to Kei whose friendship might, as someone says, essentially be too close for them to really get along. Drummer Kyoko (Aki Maeda) decides to declare her feelings for a longstanding crush before the concert. In the end she doesn’t manage it, but it doesn’t quite matter somehow because their performance is itself a kind of coming into being in which “the real us” comes into focus if also in a moment that itself becomes romanticised or idealised as an encapsulation of youth. Yamashita travels through the school festival as if it were a passage from one state of being to another, from the noodle stalls and crepe stands to haunted houses and the boy creating his own moment through encapsulating them on film, before ending with an unending song “so we can laugh tomorrow,” and the “real us” lives on.

Linda Linda Linda opens in US cinemas 5th September courtesy of GKIDS.

Trailer (English subtitles)

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair.

Nobuhiro Yamashita may be best known for his laid-back slacker comedies, but he’s no stranger to the darker sides of humanity as evidenced in the oddly hopeful Drudgery Train or the heartbreaking exploration of misplaced trust and disillusionment of My Back Page. One of three films inspired by Hakodate native novelist Yasushi Sato (the other two being Kazuyoshi Kumakiri’s Sketches of Kaitan City and Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There), Over the Fence (オーバー・フェンス) may be among the less pessimistic adaptations of the author’s work though its cast of lonely lost souls is certainly worthy both of Yamashita’s more melancholy aspects and Sato’s deeply felt despair. Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance.

Crazy uncles – the gift that keeps on giving. Following the darker edged Over the Fence as the second of two films released in 2016, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s My Uncle (ぼくのおじさん, Boku no Ojisan) pushes his subtle humour in a much more overt direction with a comic tale of a self obsessed (not quite) professor as seen seen through the eyes of his exasperated nephew. “Travels with my uncle” of a kind, Yamashita’s latest is a pleasantly old fashioned comedy spiced with oddly poignant moments as a wiser than his years nephew attempts to help his continually befuddled uncle navigate the difficulties of unexpected romance. Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives.

Starting as he meant to go on, Nobuhiro Yamashita’s debut feature film is the story of two slackers, each aimlessly drifting through life without a sense of purpose or trajectory in sight. His humour here is even drier than in his later films and though the tone is predominantly sardonic, one can’t help feeling a little sorry for his hapless, lonely “heroes” trapped in their vacuous, empty lives.