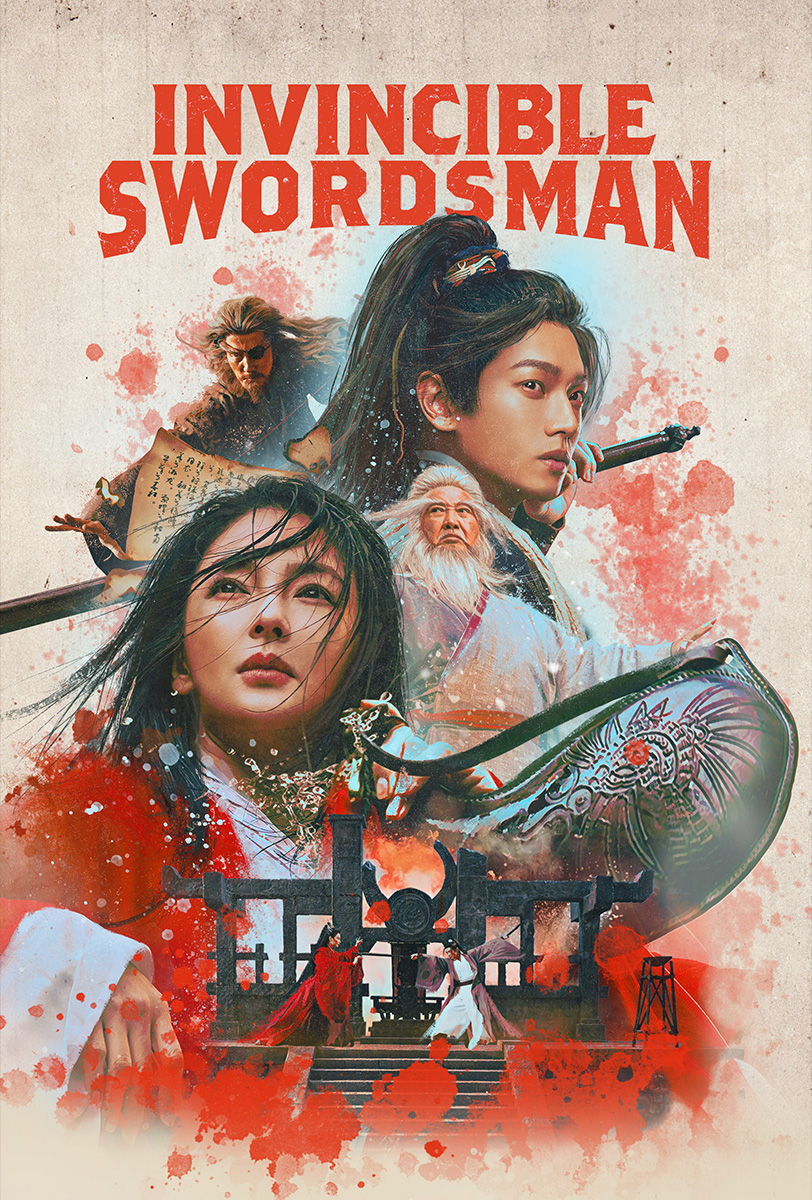

Adapted from Jin Yong’s wuxia classic The Smiling Proud Warrior, Invincible Swordsman (笑傲江湖,

xiào ào jiānghú) has a hard battle to fight in covering the same ground as 1992’s Swordsman II which featured an iconic performance from Brigitte Lin as the androgynous Invincible Asia. Produced by streaming network IQYI and Tencent, the film has a more epic feel than the studio’s similarly pitched wuxia and was also released in cinemas but is undoubtedly a much more conventional affair let down by an over-reliance on CGI.

To recap, Ren Woxing (Terence Yin Chi-Wai) led the demonic Sun and Moon Sect in despotic fashion slaughtering many of his own followers. Consequently, they flocked behind Invincible East (Zhang Yuqi ) to free them who eventually defeated Woxing and has imprisoned him in the basement of their lair. Meanwhile, drunken but earnest swordsman of the Mount Hua sect Linghu Chong (Tim Huang) has befriended Woxing’s daughter Ren Yinging (Xuan Lu) through their shared love of music and is kicked out of the clan for treason. Nevertheless, he’s taken on as a disciple by the charismatic Feng Qingyang (Sammo Hung Kam-Bo) who continues teaching him martial arts before he’s called back to the world of Jianghu by Yingying who warns him his friends are in danger after teaming up to defeat Invincible East who has now become even more despotic than Woxing in drinking the blood of their victims to stay young.

Even so, breaking Woxing out of containment so he can take out Invincible East seems like a bold plan given there’s no guarantee he’ll actually do that and even less he won’t just go back to his old ways afterwards. Linghu Chong only participates out of loyalty to his men and as a favour to Yingying and is therefore constantly insisting that none of this is anything to do with him because he’s leaving the martial arts world. It’s a fault with the source material, but it’s quite frustrating that all these women are hopelessly in love with the actually quite bland Linghu Chong who has a nasty habit of turning up every time a woman is about to fight someone and heroically standing in front of her. Ironically, that’s how he meets “Invincible East” without realising, or at least the nameless final substitute of Invincible East who has become the public face of the legendary warrior.

Christened “Little Fish,” by a besotted Linghu Chong who believes her to be a damsel in distress, she is the only female substitute of Invincible East who has undergone self-castration in order to achieve a higher level of martial arts and in the film’s conception thereby feminised. Unlike the ’92 version, however, Little Fish is concretely female and bar a brief flirtation with some of her maids more preoccupied with her lack of individual identity in having no name of her own. Consequently, her love of Linghu Chong becomes an opposing identity though she feels herself forced to take on the persona of Invincible East. Linghu Chong too is fascinated by her mystery which causes him to act in a caddish way towards Yingying who is otherwise positioned as his rightful love interest even if their romance is frustrated by the relationships of their respective clans.

What they’re really fighting is Invinsible East’s corruption of Jianghu which it wants to rule in its entirety. The corruption has already worked its way into the Mount Hua sect as ambitious couturiers vie for power and throw their lot in with the Sun and Moon sect in the hope of advancement. Luo does his best to conjure a sense of the majestic in the elaborate action set pieces, but the over-reliance on wire work and CGI particularly for the swords leaves them feeling inconsequential while there’s barely any actual martial arts content as the fights revolve around the martial arts stances rather than combat. Frequent homages to the ’92 film including the use of its iconic song also serve to highlight the disparity in scope and vision though even if Zhang Yuqi appears to be channelling Brigitte Lin there is genuine poignancy in her tragic love for Linghu Chong which is also the longing for freedom and another identity that is forever denied her. With his belief in Jianghu well and truly destroyed, Linghu Chong finds himself a lonely wanderer and refugee from a martial arts world largely devoid of hope or honour and adrift with seemingly no destination in sight.

Invincible Swordsman is released on Digital 19th August courtesy of Well Go USA.

Trailer (English subtitles)