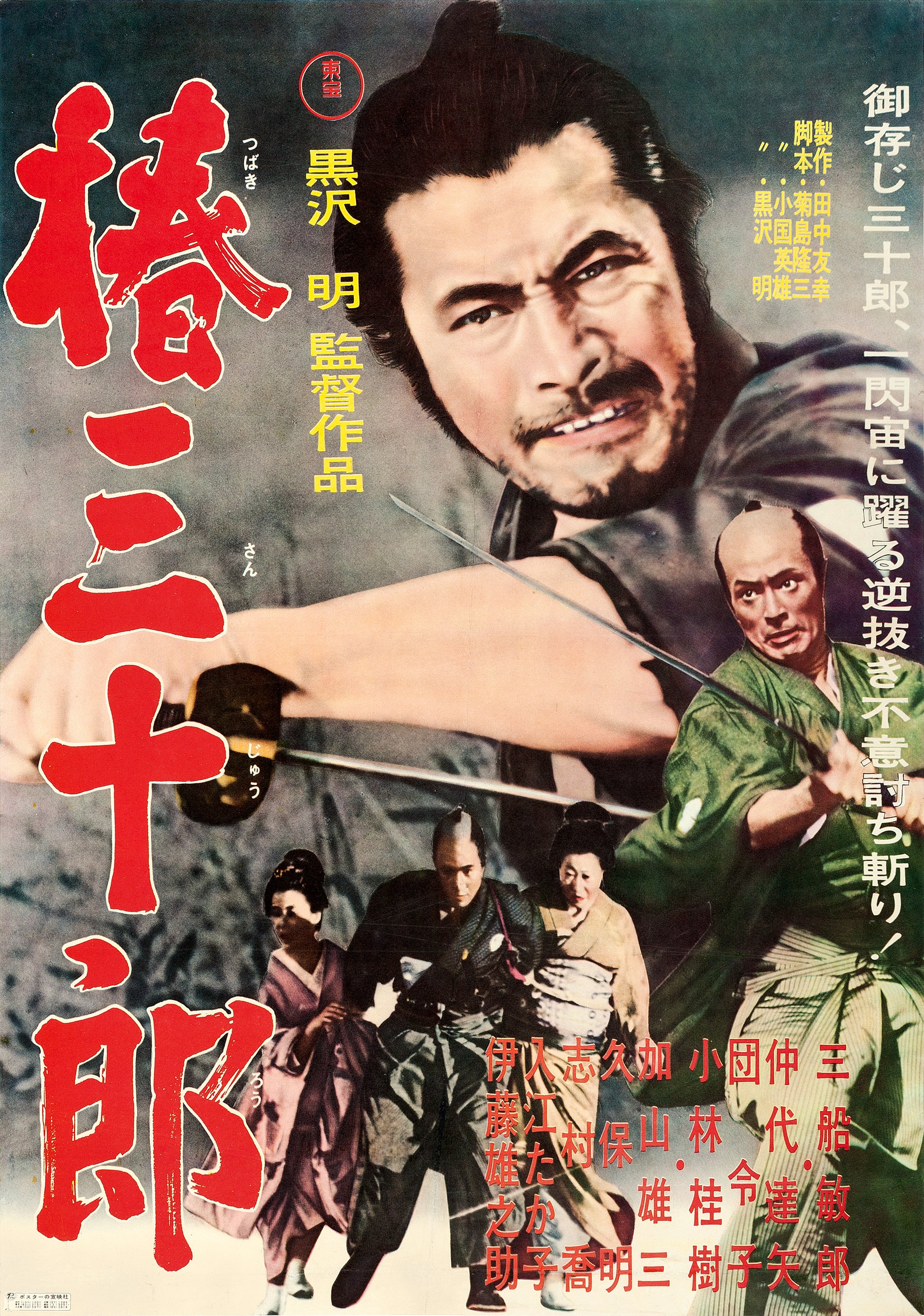

Adapted from a novel by Shugoro Yamamoto, Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo had taken place in a world of collapse in which the foundations of the feudal order had begun to crack while the disruptive allure of hard currency had left ordinary people at the mercy of gang intimidation in place of exploitative lords. A quasi-sequel or perhaps more accurately termed a companion piece, Sanjuro (椿三十郎, Tsubaki Sanjuro) by contrast, takes place in a world that should be peaceful and orderly but suggests that the corruption was there all along and tolerated to the extent of being coded into the system.

The accused man, Mutsuta (Yunosuke Ito), says as much at the film’s conclusion explaining that he meant to deal with the matter “more discreetly” after amassing incontrovertible evidence he could he could offer to his superiors in the capital if only his hot-headed nephew and the idealistic young samurai with him hadn’t jumped the gun by naively thinking they could expose conspiracy by force of will. This time around, the wandering ronin who gives his name as Sanjuro (Toshiro Mifune) finds himself adopting a fatherly position trying to convince the youngsters to think before they act. Overhearing their conversation, he explains to them that they have mostly likely been misled, Mutsuta is innocent and his attempt to warn them off well-meaning while the superintendent Kikui (Masao Shimizu) is the real villain and almost certainly intends to have the lot of them bumped off before they figure out what’s really going on.

Unlike Yojimbo, Sanjuro takes place entirely within samurai society which ought to be an orderly place where everyone follows the same code and does their best to act honourably. This sense of stability is reflected in Kurosawa’s composition which leans closer to the classicism of the historical drama than the windswept vistas of the lonely ghost town in Yojimbo, and by the contrast so often drawn between the wandering ronin and the young samurai who are shocked by his rough way of speaking and wilful rejection of the politeness with which they have been raised. As a captured prisoner points out, Sanjuro has a sarcastic manner and a tendency to insult where he means to praise which further fuels the doubt some have in him, unsure whether they can really trust this “outspoken and eccentric” drifter fearing he will simply sell himself to the highest bidder and betray them. Mutsuta sympathises with this to some degree, forgiving the boys for having thought him a villain but lamenting that his long face has often got him into trouble. They thought he was the bad guy because he looked like one and trusted Kikui because he looked honest, laying bare the childish superficiality soon corrected by the well honed instincts of the veteran Sanjuro.

It’s this superficiality that also leads them to dismiss the advice of Lady Mutsuta (Takako Irie) as “hopelessly naive” while only Sanjuro can see that she has a full grasp of the situation at hand and accepts her admonishment that he has the “bad habit” of killing too easily when another solution may be available. When the boys catch one of Kikui’s henchmen they suggest killing him because he’s seen their faces, but Lady Mutsuta decides to invite him into their home, assuring him he won’t be harmed and even giving him one of their fancy kimonos to wear. The man seems to have been won over by their hospitality, sometimes emerging from the cupboard where he is (voluntarily) imprisoned to offer a word of advice along with a defence of Sanjuro having observed him and figured out that he is a good man with an admittedly gruff manner that makes him a bad fit for conventional samurai society. “He would find it too confining here,” Mutsuta agrees, “he wouldn’t wear these fine garments or be a docile servant of the clan.”

In any case, the film doesn’t particularly reject samurai society only suggest that if you’re going to live within it you should follow the rules and if you can’t you should follow your own path as Sanjuro has been doing in a sense “freed” by his ronin status serving no master but himself. Lady Mutsuta had a point when she said that he glistened like a drawn sword, something he too concedes after facing off against his final foe, Heibei (Tatsuya Nakadai), whom he describes as much like himself another drawn sword in a society in which direct violence is inappropriate as the explosive spray of blood on Heibei’s all too matter of fact defeat makes plain. “The sword is best kept in its sheath” she reminds him, she and her husband both suggesting that this world is ruled by intrigue which is why Mutsuta hoped to handle the corruption “discreetly” though he won’t condemn the young men for their desire to enforce the rules of their society and stand up against corruption and injustice. Their rebellion has accidentally led to unnecessary deaths because of their youthful hot-headedness and tendency towards the simplistic solution of violence, but all things considered it has worked out well enough for all concerned. And so, his work done, Sanjuro is left to wander telling the boys not to follow him because he too is a disruptive and dangerous a presence in this codified world of peace and order in which a sword loses its value the moment it is drawn.

Sanjuro screened at the BFI Southbank, London as part of the Kurosawa season.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made

The Invisible Man is a frightening presence precisely because he isn’t there. The living manifestation of the fear of the unknown, he stalks and spies, lurking in our imaginations instilling terror of evil deeds we are powerless to stop. Daiei made  Placed between

Placed between

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.

Japan’s kaiju movies have an interesting relationship with their monstrous protagonists. Godzilla, while causing mass devastation and terror, can hardly be blamed for its actions. Humans polluted its world with all powerful nuclear weapons, woke it up, and then responded harshly to its attempts to complain. Godzilla is only ever Godzilla, acting naturally without malevolence, merely trying to live alongside destructive forces. No creature in the Toho canon embodies this theme better than Godzilla’s sometime foe, Mothra. Released in 1961, Mothra does not abandon the genre’s anti-nuclear stance, but steps away from it slightly to examine another great 20th century taboo – colonialism and the exploitation both of nature and of native peoples. Weighty themes aside, Mothra is also among the most family friendly of the Toho tokusatsu movies in its broadly comic approach starring well known comedian Frankie Sakai.