Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.

Like most directors of his era, Shohei Imamura began his career in the studio system as a trainee with Shochiku where he also worked as an AD to Yasujiro Ozu on some of his most well known pictures. Ozu’s approach, however, could not be further from Imamura’s in its insistence on order and precision. Finding much more in common with another Shochiku director, Yuzo Kawashima, well known for working class satires, Imamura jumped ship to the newly reformed Nikkatsu where he continued his training until helming his first three pictures in 1958 (Stolen Desire, Nishiginza Station, and Endless Desire). My Second Brother (にあんちゃん, Nianchan), which he directed in 1959, was, like the previous three films, a studio assignment rather than a personal project but is nevertheless an interesting one as it united many of Imamura’s subsequent ongoing concerns.

Set in the early 1950s, the film focuses on four children who find themselves adrift when their father dies leaving them with no means of support. The father had worked at the local mine but the mining industry is itself in crisis. Many of the local mines have already closed, and even this one finds itself in financial straits. Despite the foreman’s promise that he will find a job for the oldest son, Kiichi (Hiroyuki Nagato), there is no work to be had as workers are being paid in food vouchers rather than money and strike action frustrates what little production there is. After receiving the unwelcome suggestion of work in a “restaurant” in another town, Yoshiko (Kayo Matsuo) manages to find a less degrading job caring for another family’s children (though she receives only room and board, no pay for doing so). With younger brother Koichi (Takeshi Okimura) and little sister Sueko (Akiko Maeda) still in school, it seems as if the four siblings’ days of being able to live together as a family may be over for good.

Based on a bestselling autobiographical novel by a ten year old girl, My Second Brother is one of the first films to broach the Zainichi (ethnic Koreans living in Japan) issue, even if it does so in a fairly subtle way. The four children have been raised in Japan, speak only Japanese and do not seem particularly engaged with their Korean culture but we are constantly reminded of their non-native status by the comments of other locals, mostly older women and housewives, who are apt to exclaim things along the lines of “Koreans are so shiftless” or other derogatory aphorisms. Though there are other Koreans in the area, including one friend who reassures Kiichi that “We’re Korean – lose one job, we find another”, the biggest effect of the children’s ethnicity is in their status as second generation migrants which leaves them without the traditional safety net of the extended family. Though they do have contact with an uncle, the children are unable to bond with him – his Japanese is bad, and the children are unused to spicy Korean food. They have to rely first on each other and then on the kindness of strangers, of which there is some, but precious little in these admittedly difficult times.

In this, which is Imamura’s primary concern, the children’s poverty is no different from that of the general population during this second depression at the beginning of the post-war period. The film does not seek to engage with the reasons why the Zainichi population may find itself disproportionately affected by the downturn but prefers to focus on the generalised economic desperation and the resilience of working people. The environment is, indeed, dire with the ancient problem of a single water source being used by everyone for everything at the same time with all the resultant health risks that poses. A young middle class woman is trying to get something done in terms of sanitation, but her presence is not altogether welcome in the town as the residents have become weary of city based do-gooders who rarely stay long enough to carry through their promises. The more pressing problem is the lack of real wages as salaries are increasingly substituted for vouchers. The labour movement is ever present in the background with the Red Flag drifting from the mass protests in which the workers voice their dissatisfaction with the company though the spectre of mine closure and large scale layoffs has others running scared.

One of the most moving sequences occurs as Koichi and another young boy ride a mine cart up the mountain and talk about their hopes for the future. They both want to get out of this one horse town – Koichi as a doctor and his friend as an engineer, but their hopes seem so far off and untouchable that it’s almost heartbreaking. Sueko skipped school for four days claiming she had a headache because her brother didn’t have the money for her school books – how could a boy like Koichi, no matter how bright he is, possibly come from here and get to medical school? Nevertheless, he is determined. His father couldn’t save the family from poverty, and neither could his brother but Koichi vows he will and as he leads his sister by the hand climbing the high mountain together, it almost seems like he might.

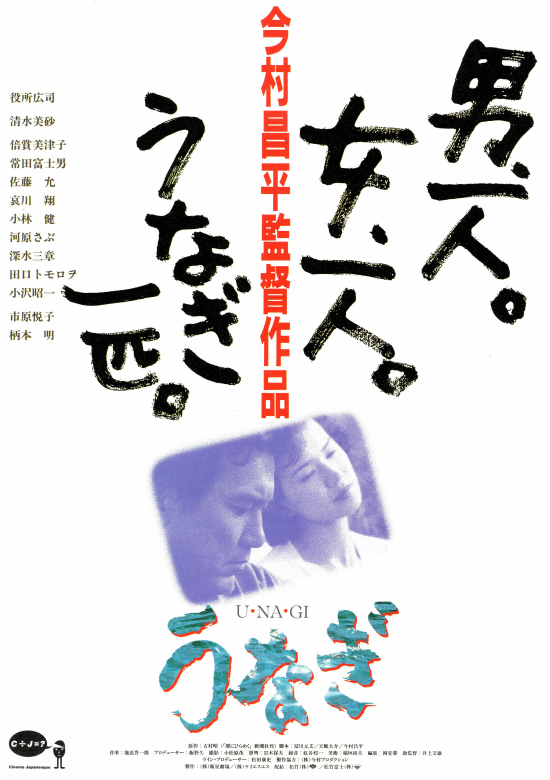

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come. The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration

The bright and shining post-war world – it’s a grand place to be young and fancy free! Or so movies like Tokyo Mighty Guy (東京の暴れん坊, Tokyo no Abarembo) would have you believe. Casting one of Nikkatsu’s tentpole stars, Akira Kobayshi, in the lead, Buichi Saito’s Tokyo Mighty Guy is, like previous Kobayashi/Saito collaboration