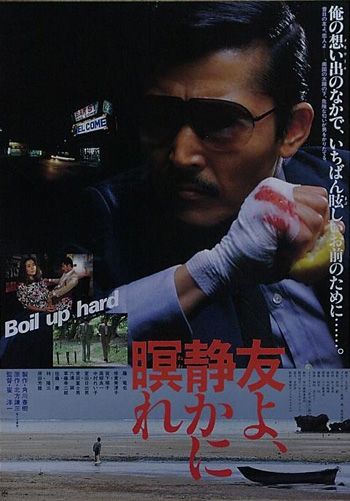

Kiyoshi Nishimura began his career in the action genre with a series of paranoid thrillers so it feels particularly odd to see him tackle similar themes in such a breezy, lighthearted way as 1979’s Golden Partners (黄金のパートナー, Ogon no Partner). Though based on a novel by Kyotaro Nishimura, the film seems to have been envisioned as an homage to Robert Enrico’s Les Aventuriers in following two men and a young woman on a quest to track down a missing person and also find a large amount of gold supposedly contained in a downed submarine.

Kosuke (Tomokazu Miura) is a rather aimless young man who lives on a fishing boat and has a career as a freelance photographer taking photos of things people would rather weren’t photographed, while his best friend Shusaku (Tatsuya Fuji) is a motorcycle-riding policeman who has a strong sense of civic duty yet mostly spends his time giving out tickets to locals traveling slightly over the speed limit. They’re both good friends with the landlord at the Polestar bar whom they affectionately refer to as Pops (Taiji Tonoyama). Pops has let them run up a significant tab even though he doesn’t appear to have any other customers. In any case, their aimless days are interrupted when Kosuke begins hearing a strange SOS message but can’t seem to identify where it’s coming from to be able to help. Meanwhile, a young woman arrives looking for Pops and explains that her father, an old friend of his, has gone missing which may be connected to the mysterious stash of gold bars Pops is fond of talking about every time he has too much to drink.

Figuring out that the SOS message is using a code employed by the Imperial Navy during the war, the trio embark on trying to solve the mystery partly to help the young woman, Yukibe (Misako Konno), and partly because they want to find the gold. Basically a buddy movie, the film has a childlike quality as it mainly follows the trio hanging out on the beach in Saipan solving puzzles and getting into minor arguments. Things take a slightly darker turn when Shusaku decides to stay on even after his paid leave from the police force ends despite realising it’s unlikely they’re going to find the gold bars or even figure out what’s happened to Yukibe’s father. Having realised that Yukibe likes Kosuke and despite his own feelings for her, he’s beginning to feel like a third wheel but in the end cannot bring himself to leave this unending holiday adventure.

But after making a shocking discovery, what they stumble on is a wartime conspiracy in which a corrupt spy killed the other men assigned to transport the gold and took it for himself. He then used it to become a rich and powerful man in post-war Japan, apparently suffering no consequences for his actions hinting at the essential corruption of the post-war society. Realising he likely can’t be prosecuted nor would justice really be served if he went to prison for a few years, they decide on blackmail as their way of recovering the gold little realising how far someone who has killed before will go to protect their secrets. Nevertheless, despite the conspiratorial overtones the atmosphere remains largely cartoonish rather than dark or threatening right up until another tragedy occurs and brings the whole thing to an end.

This laidback sensibility is aided by the soundtrack provided by Takao Kisugi who briefly appears at the end of the film as his city pop folk songs run constantly throughout. Nishimura’s use of a ghostly zero fighter as the gang investigate the former airbase on Saipan proves slightly uncomfortable though ties in with some ghostly imagery as an evocation of a past that’s apparently still very present and largely unresolved. In any case, like a classic children’s adventure story the film does not particularly engage with its larger themes but concentrates on the trio’s attempts to solve the mystery along with their zany plans and crazy stunts culminating in the guys parachuting out of a private plane after aiming it right at that of the bad guys in a moment of extreme irony. A little bit sad and more tragic than it perhaps ought to be, the film is nevertheless a warmhearted tale of male friendship, the childish glee of solving a mystery, and the satisfaction of getting one over on the bad guys even if it comes at a very high price.

Trailer (no subtitles)