For his last film in Hong Kong before decamping to Hollywood, Ronny Yu looked back to a lost classic in loosely remaking 1937’s Song at Midnight, itself loosely based on Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera. A Hong Kong/Singapore co-production, the film was, perhaps surprisingly, shot entirely in Beijing where Yu constructed an opulent set including a full-scale replica of the theatre which he then burnt down for real during the legendary climax of the classic story.

Set in 1936 (one year before the release of A Song at Midnight and the intensification of the Sino-Japanese war), the film opens with a gothic scene of carriages racing through the fog. A troupe of left-wing actors has come to make use of a ruined theatre to put on their revolutionary play. On arrival, the troupe’s leading man Wei Qing (Lei Huang), who is in a relationship with leading lady Landie (Liu Lin) but claims he is too poor to marry so they will have to wait until he’s famous, is captivated by the auditorium, convinced he can hear strange sounds of a woman singing. The strangeness of the surroundings continues to bother him until he finally decides to ask creepy caretaker Uncle Ma (Cheung Ching-Yuen)to disclose what he knows of the fire which destroyed the theatre 10 years previously.

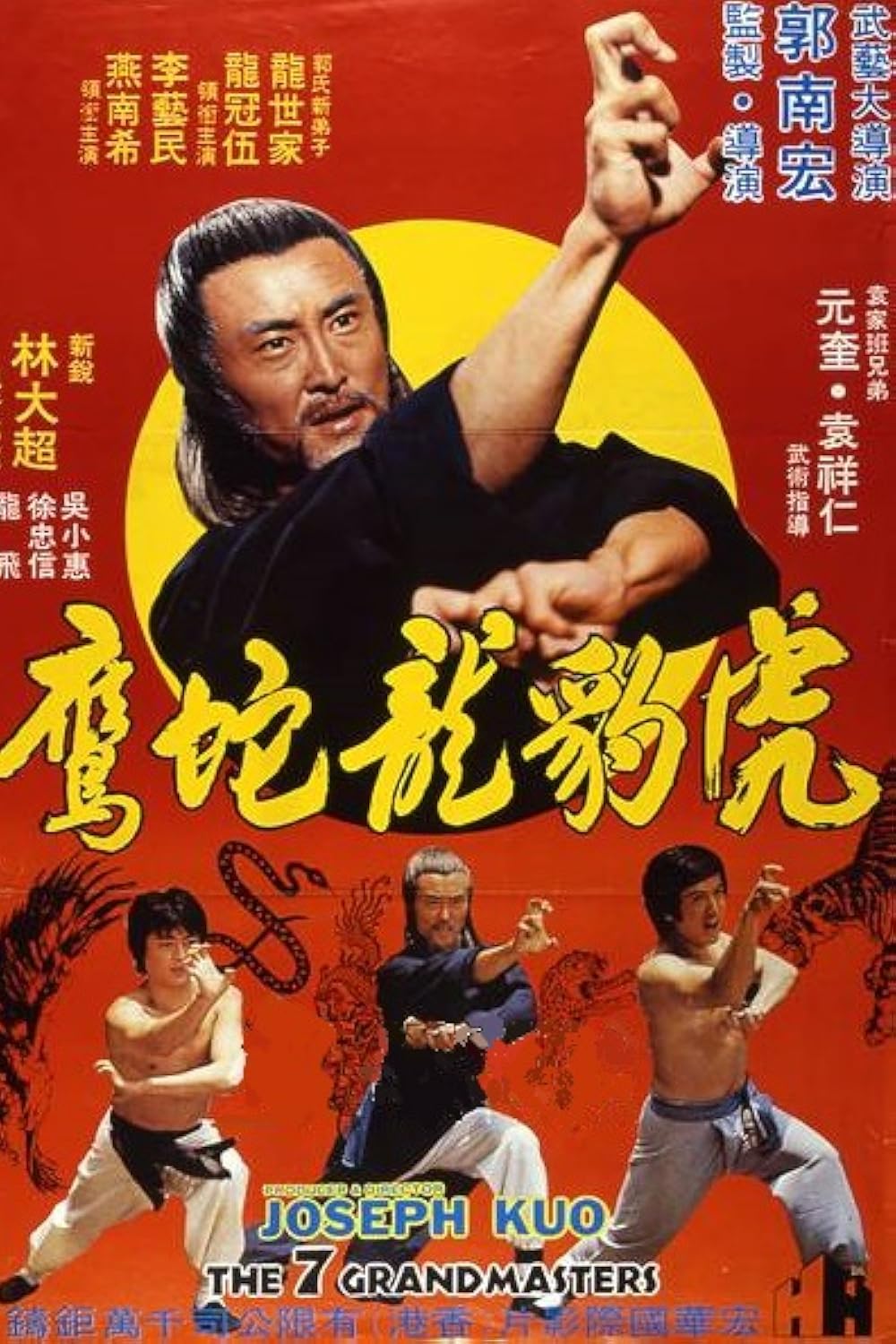

Counter-intuitively, Yu shoots the ‘30s sequence in a washed-out sepia with occasional flashes of colour almost like hand-tinted photographs. As Ma spins his story, we transition into a sumptuous world of reds and golds in the old opera house designed, as we’re told, by the famous actor Song Danping (Leslie Cheung Kwok-Wing) who is said to have perished along with it in the fire. Danping, to whom Wei Qing is constantly likened, was the greatest actor of the age famous for his performances in Western theatre, such as the Mandarin musical adaptation of Romeo and Juliet in which he was performing immediately before his death. In a case of life imitating art, Danping had fallen in love with the daughter of a wealthy family, Yuyan (Geng Xiao-Lin), and wished to marry her, but actors belong to an undesirable underclass and in any case, Yuyan’s father had already arranged her marriage to the idiot son of a powerful politician, Zhao (Bao Fang), in exchange for smoothing the path for his new factory enterprise.

In a direct reversal of the 1937 film, it is Wei Qing who is the left-wing revolutionary proudly singing communist songs about the “national humiliation” which, it seems, partly accounts for their low audience numbers, while Danping is the reactionary libertine performing in “decadent” Western theatre which seemingly has no political import other than its capacity to cause annoyance to the conservative older generation extremely concerned about Danping’s effect on the local young women. With that in mind, it seems strange that Wei Qing is so quick to accept Danping’s offer once he finally reveals himself and drops the playbook for Romeo and Juliet into his hands. Nevertheless he is content to accept the older man’s tutelage, hoping that the increased revenue will save the troupe and, as implied earlier, he doesn’t actually seem to be very invested in the idea of revolution so much becoming famous.

Nevertheless, it turns out that he does indeed have integrity. To gain additional funding, the troupe’s leaders end up schmoozing with none other than Zhao, the man who eventually married Yuyan after the fire but quickly discarded her on learning she was not a virgin. Now apparently having risen in politics in Shanghai, Zhao is a misogynistic bully carrying a grudge towards women because of his humiliation by Yuyan. In the scene in which we re-meet him, no longer quite so moronic but definitely nastier, he forces his dining companion to eat 60 meat buns because she had the temerity to declare herself full and try to leave the table. When Wei Qing snaps at him he takes a liking to Landie who is more or less pimped out by the impresario in the same way that Yuyan was sold by her father to the Zhaos in order to further his business interests. On discovering Yuyan, who has since descended into madness, wandering the streets, he stops his carriage to give her a public whipping, ranting about how he had her 10 years preciously but she turned out to be a “slut” who’d already slept with the famous actor Song Danping which seems like a curious thing to announce in the public square.

Then again, these fascist stooges have an odd approach to public humiliation, stopping Danping’s play mid-performance to call out Yuyan which seems like a counter-intuitive and extremely embarrassing move when they could simply have dragged her out of her box. Danping strikes a minor victory for art when he get the goons ejected from the theatre by the irate audience who, he points out, have had their evening spoiled by officials misusing their authority for a spot of personal pettiness. The intervention is mirrored in the film’s conclusion with the “villains” effectively put on trial in the theatre, as theatre, with an appeal made to law enforcement which is eventually successful as the police commander affirms his intention to act for the public good (though in this case is also serving his own while ironically giving justification to mob rule).

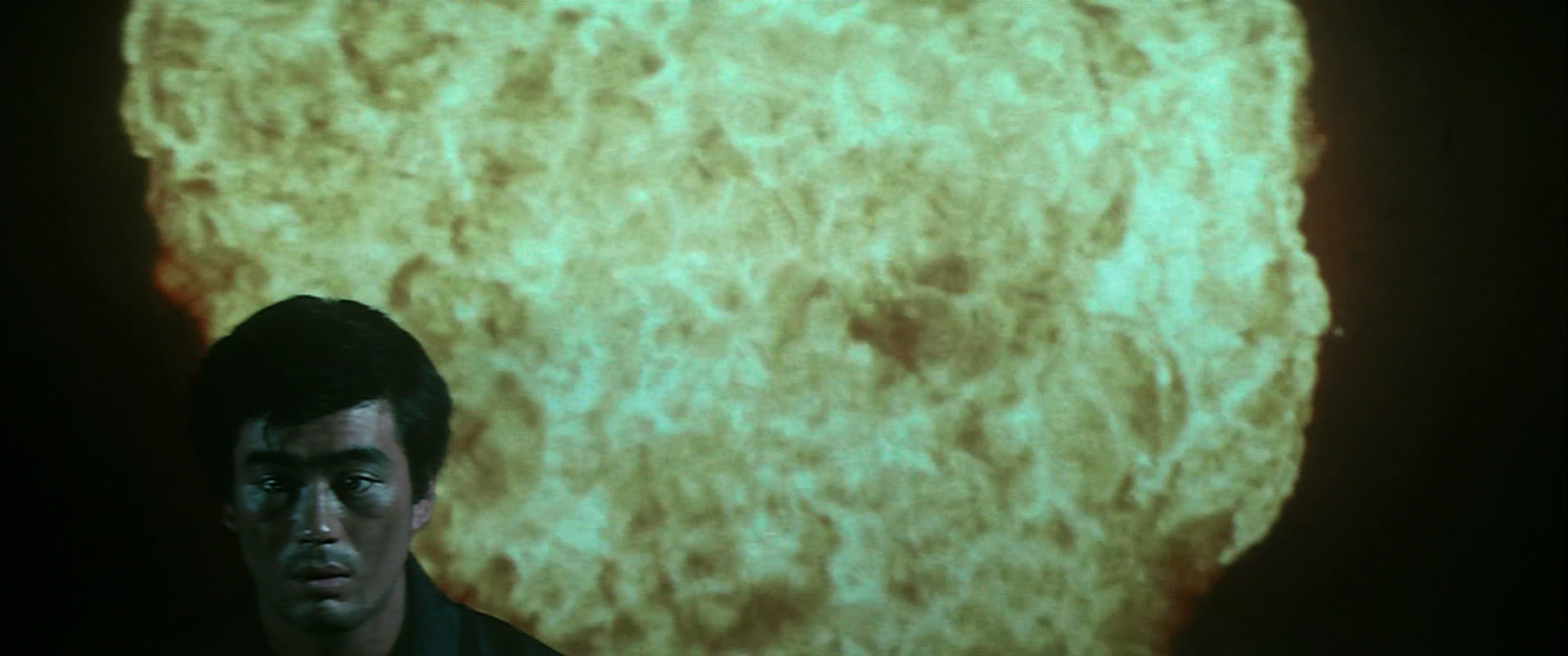

Despite all of that, however, the major stumbling block to the tragic romance turns out to narcissistic vanity on the part of former matinee idol Danping who has been hiding himself away even though he knows Yuyan has gone mad in love for him simply because his face was ruined when Zhao’s goons threw acid at it and then locked him in the burning theatre. He contents himself with singing on nights when the moon is full knowing that hearing his voice on such occasions is the only thing keeping her going. On learning of his mentor’s true purpose to make Yuyan think he, the handsome young actor, is the Danping of old, Wei Qing is extremely conflicted, unable to understand why the now ghoulish Danping would put Yuyan through so much grief when he could simply have revealed himself a decade ago. Nevertheless, realising the intensity of the romantic suffering all around him perhaps pushes him towards ”forgiving” Landie for having schmoozed with Zhao.

Full on gothic melodrama, Yu’s adaptation of the classic story is all fog and cobwebs, situating itself in a world which is already falling apart. In photographing the 30s in washed-out greys, he perhaps suggests that something has already faded, or at least become numb, in comparison with the life and colour of mid-20s Shanghai in all its art deco glory. Yet even in giving us a superficially happy ending in which justice, moral and romantic, appears to have been served Yu denies us the resolution we may be seeking with a melancholy title card reminding us that happiness in the China of 1936 may be a short-lived prospect.