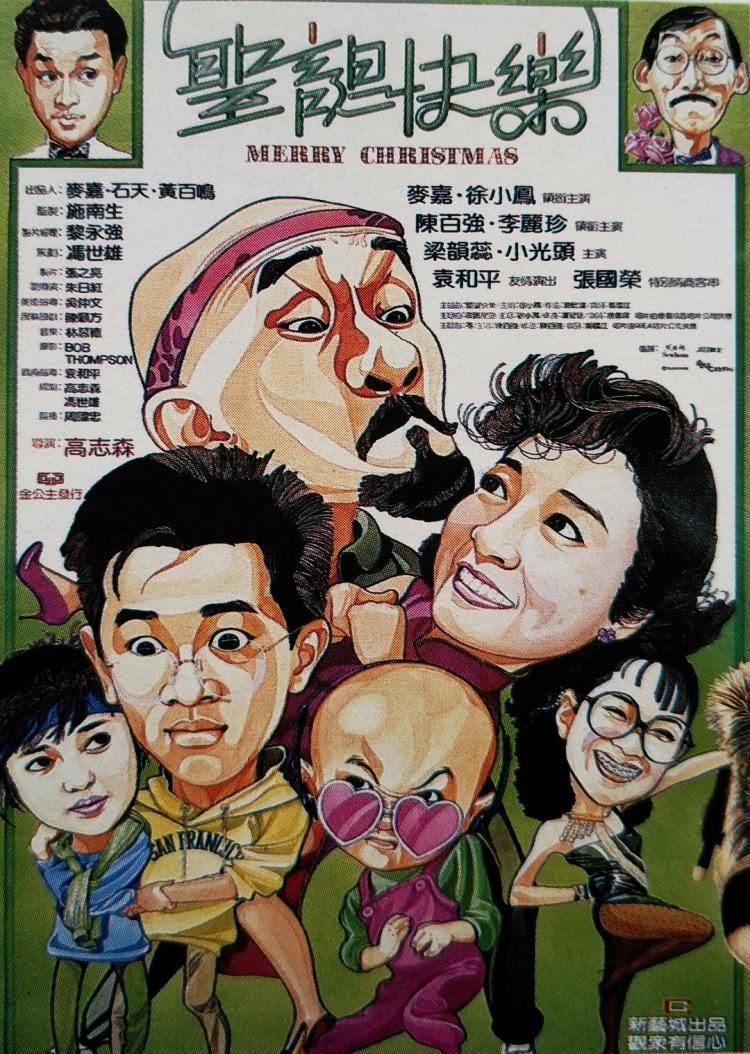

The Lunar New Year movie solidified itself as a concept in the early ‘80s and is often an occasion for heartwarming silliness celebrating food and family. Arriving in 1984, Merry Christmas (聖誕快樂) shifts the zany action up to the Western festive season as a widowed Hong Kong dad struggles to express his feelings for the woman next-door who’s been looking after his young son while his two grown up kids contend with romantic troubles of their own in the rapidly developing city.

The Lunar New Year movie solidified itself as a concept in the early ‘80s and is often an occasion for heartwarming silliness celebrating food and family. Arriving in 1984, Merry Christmas (聖誕快樂) shifts the zany action up to the Western festive season as a widowed Hong Kong dad struggles to express his feelings for the woman next-door who’s been looking after his young son while his two grown up kids contend with romantic troubles of their own in the rapidly developing city.

“Baldy” Mak (Karl Maka) is a newspaper editor who lost his wife some time ago. Though everyone else is getting into the holiday spirit, Baldy is celebrating his birthday which gives his goodnatured colleagues an excellent excuse to prank him and though it ends in him getting joke fired, it does eventually bring him a bonus and a new car. Meanwhile, he and the kids – earnest teenage son Danny (Danny Chan Bak-Keung) and aspiring model Jane (Rachel Lee Lai-Chun), are largely dependent on their neighbour, Aunty Paula (Paula Tsui Siu-Fung), for domestic assistance including looking after Baldy’s toddler son, Baldy Junior, while he’s out at work. Danny and Jane are hoping their dad will eventually ask Paula to marry him, but he remains diffident. Until, that is, she drops the bombshell that she might not be able to look after Junior anymore because she’s had a letter from her cousin in America (Yuen Wo-Ping) who wants to marry her and she’s thinking of emigrating to be with him.

Baldy, not a bad man but unafraid to resort to underhanded tactics, spends the rest of the picture avoiding telling Paula how he really feels in favour to trying to break up her possible romance with her cousin. An early joke sees him fighting for parking spaces in his beaten up car, something which eventually gets him into an argument with the good-looking yet similarly underhanded John (Leslie Cheung Kwok-Wing) who fakes a limp to get nearby bystanders to push Baldy’s car out of the way, causing Baldly to try and get his own back only for it to hilariously backfire. John, meanwhile, takes an instant liking to Baldy’s daughter Jane, which instantly gets Baldy on edge. A typically strict dad, he takes Danny aside to instruct him about how to get the best bang for his buck taking girls to the pictures, but is quick to warn Jane that no man can be trusted and she’s to be home by 10pm at the latest. Needless to say, it’s a moment of minor embarrassment for him when the guys at work are looking at tasteful glamour shots to include in the paper only to discover that Jane’s been earning a few extra pennies as a model.

The double standards only increase as Baldy and Danny hatch a plan to put Paula’s cousin off by convincing him she’s actually a sex worker and in debt to a sleazy pimp. Meanwhile, Baldy takes him out on the town to show him a few sights while setting up amusing tableaux that make him out to be a violent pervert, groping women, kissing men, and kicking little kids in the face. Paula, meanwhile, remains thoroughly fed up with Baldy’s antics, keeping her composure when he tries to make her jealous by dressing like a teenager and cosying up to Danny’s love interest “Jaws” (beautified by getting her braces taken off and wearing contacts), but asking her cousin to secretly record everything Baldy says to him on their weird “date” around Hong Kong.

Charming period details abound, like the “3D” adult movies Baldy rents (and inappropriately watches with Baldy Junior) which have to be watched with “sunglasses”, and Baldy’s constant inability to hail a cab coupled with his atrocious parking techniques and delightful pre-photoshop efforts to frame the cousin and then expose him with a slideshow lecture delivered solely for Paula’s benefit. Meanwhile, the festive spirit is ever present with the ubiquitous Christmas trees, Poinsettia forest outside Baldy’s door, and seasonal set piece at Paula’s nightclub. Delightfully silly, Merry Christmas is a zany holiday treat, a middle-aged rom-com in which a slightly ridiculous widower and a lonely nightclub singer discover the courage to fight for love thanks to a little Christmas magic and the fierce support of meddling family members.

Original trailer (no subtitles)