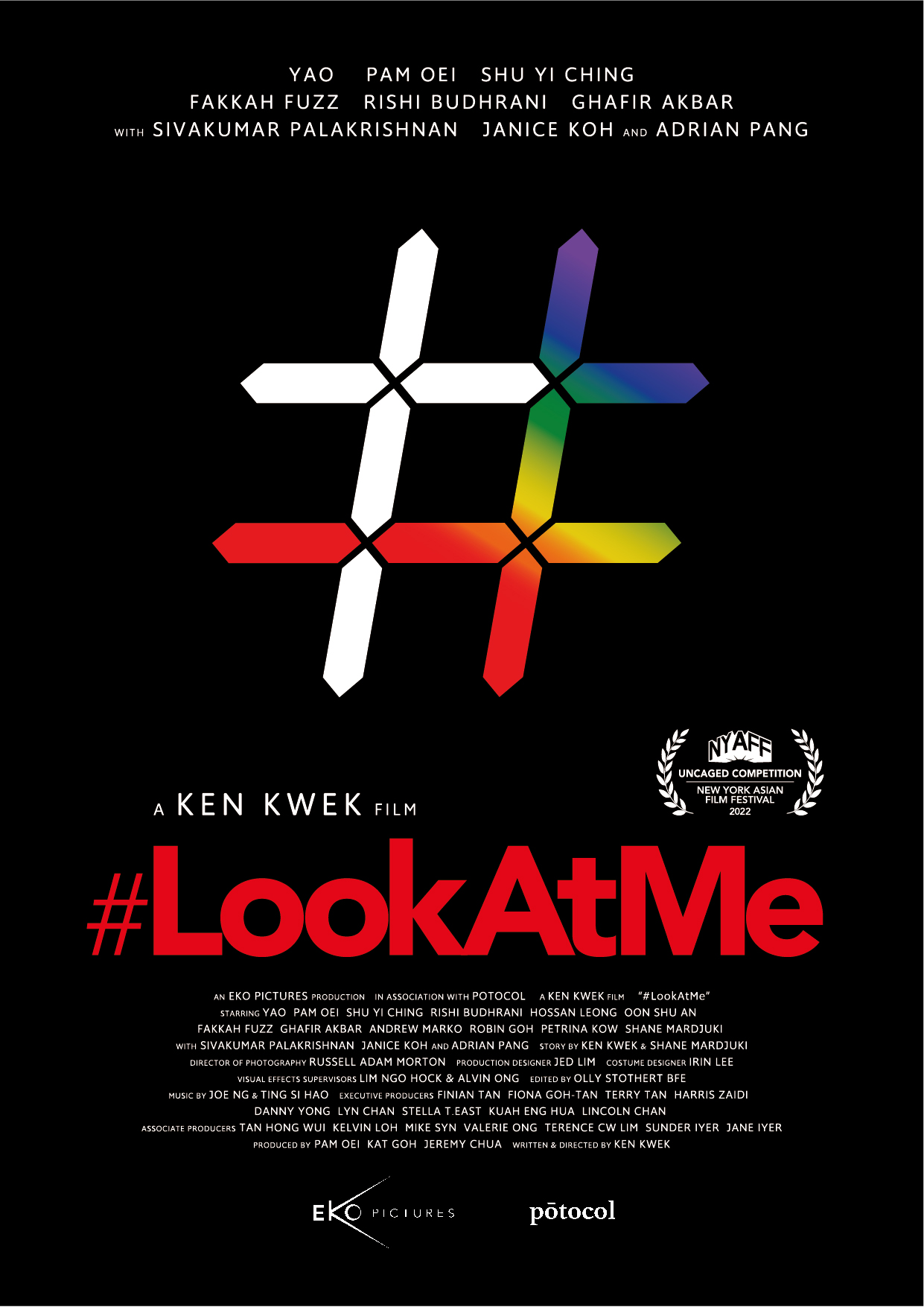

The unequal authoritarianism of contemporary Singapore conspires against an aspiring YouTuber in Ken Kwek’s surreal drama #LookatMe. Opening with a title card explaining that 2015 prominent activists have jailed for breaking arbitrary laws relating to obscenity and illegal assembly, the film throws its progressive hero into a kafkaesque quest for justice after he’s arrested for publishing a video mocking a homophobic religious figure simultaneously asking why it’s alright for a pastor to spout hate speech but illegal to challenge him and pitting the hero’s desire for fame against that for genuine social change.

Sean (Yao) does indeed want fame, running an unsuccessful YouTube channel while alternating between mocking more successful stars and emulating them by playing cruel pranks on his understanding mother in the hope of going viral. His life changes when his girlfriend Mia (Shu Yi Ching), whose parents are religious, invites him, and his gay twin brother Ricky (also Yao), to attend an evening service at her church in an attempt to curry favour. The church turns out to be of the evangelical variety, opening with a Christian rock performance before showman pastor Josiah (Adrian Pang) arrives on stage and embarks on a homophobic rant insisting that he has no problem with gay people but is dead against them overturning Singapore’s colonial era law criminalising homosexual sex. Ricky is obviously upset, unsure why Mia whom he assumed to be progressive would have invited him to such an event, and leaves abruptly upsetting Mia’s father in the process.

Sean is so outraged by the whole thing that after noticing that Josiah gets a lot more hits than he does with his hate speech, he makes a video mocking his messaging and satirically accusing him of bestiality which eventually goes viral but also gets him arrested after the church’s many followers ring the local police en masse. Sean can’t understand why he’s in trouble with the law for publicly insulting a religious leader while Pastor Josiah is seemingly free to spread dangerous and hateful ideas with no fear of challenge or dissent. Banned from social media, he’s picked up again for making an apology video and is then eventually sent to prison for 18 months while facing a defamation trial in his absence.

Even his new cellmates can’t quite believe he’s been put away for something as ridiculous as a YouTube video yet his plight exemplifies the authoritarianism of the contemporary society in which there is no guarantee of free speech nor safe path to protesting injustice. Ricky is later arrested too for “illegal assembly” when he and three friends hold up a banner protesting the case because four people outside together is apparently prohibited by law. As he points out, how are you supposed to hold up a giant banner with only three people? Sean tried to stand up for Ricky, and Ricky does the same for Sean deciding to come completely out of the closet as an LGBTQ+ activist with the support of their mother Nancy (Pam Oei) as they fight for justice but then faces random violence on the streets from homophobic vigilantes while she is later fired from the primary school where she works after refusing to sign an apology or renounce her political views.

The film takes aim at social hypocrisy as Sean is sexually abused by the prison warden while inside, and the pastor seeks to preserve his business interests calmly telling Nancy that he bears her no grudge but won’t drop his defamation suit because he has to protect the Church from similar forms of attack. He says this while lounging around on his yacht while servants bring him drinks, clearly incredibly wealthy from the proceeds of his religious life which whichever way you look at it is not a good look. In any case the film’s ironic conclusion which vindicates Sean and the place of video in social protest cannot but seem a little flippant in its implications which reduce the pastor to the position of hypocritical villain while Ricky’s conversion to Christianity feels like too much of a concession even if making clear that it is not religiosity that is being demonised only those like Josiah who would seek to profit from hate and repression. Nevertheless, Kwek presents an alternately heartwarming and harrowing vision of a close family torn apart by outdated and irrational laws and in the end left only with violence as a potential motivator for change.

#LookAtMe screened as part of this year’s New York Asian Film Festival.

NYAFF trailer (English subtitles)