Anyone who follows Korean cinema will have noticed that Korean films often have a much bleaker point of view than those of other countries. Nevertheless it would be difficult to find one quite as unrelentingly dismal as A Mere Life (벌거숭이, Beolgeosungi). Encompassing all of human misery from the false support of family, marital discord, money worries, and the heartlessness of con men, A Mere Life throws just about everything it can at its everyman protagonist who finds himself trapped in a well of despair that not even death can save him from.

Anyone who follows Korean cinema will have noticed that Korean films often have a much bleaker point of view than those of other countries. Nevertheless it would be difficult to find one quite as unrelentingly dismal as A Mere Life (벌거숭이, Beolgeosungi). Encompassing all of human misery from the false support of family, marital discord, money worries, and the heartlessness of con men, A Mere Life throws just about everything it can at its everyman protagonist who finds himself trapped in a well of despair that not even death can save him from.

Park Il-rae (Kin Min-hyuk) and his wife Yurim (Jang Liu) own a small supermarket which isn’t doing so well. After approaching both of their parents for help and getting a flat no from both directions, the couple decide to throw all of their savings into buying a delivery van to increase their business potential. Il-rae excitedly travels into the city to sign the paperwork but gradually realises something is wrong when the salesman suddenly disappears. Having lost all of the family’s money, Il-rae travels home dejected and hits on a drastic solution – a family suicide. Poisoning his wife and son, Il-rae means to die too but survives even more burdened by guilt and regret than before. More failed suicide attempts follow as Il-rae attempts to come to terms with his actions, somehow surviving yet all but dead inside.

There really is no hope for Park Il-rae. At the very beginning of the film, the family visit a park in which his wife urges their son to make a wish by adding a stone to the top of a cairn, only to see the whole thing suddenly collapse in front of them like a grim harbinger of the way their lives are about to implode. Il-rae tries to repair the pile, but all to no avail. This quite awkward family trip in which Il-rae moodily strides on ahead will actually be the happiest they ever are, away from the destructive domestic environment where money troubles and male pride cast a shadow over an otherwise ordinary family life.

Both Il-rae and his wife seem to have strained relationships with their parents. Il-rae tries his own father first in the quest for help only for him to angrily tell his son to man up. When his wife visits her parents (alone with the couple’s little boy) it’s the first time she’s seen them in a decade and they are fairly nonplussed that it’s money she’s come for. After Yurim delicately states her predicament, her father tells her that he can’t help because he now has lots of hobbies which all require money. Offering perhaps the worst piece of fatherly advice ever uttered, he suggests she take up something fun herself and not worry about money so much.

The worse things get the more the family fragments. Il-rae drinks while the couple’s son seems to be addicted to video games. Faced with an obnoxious man who thoughtlessly parks his expensive car directly in the doorway of their store yet refuses to move because “he’ll only be a few minutes”, Il-rae is only saved from doing something stupid by his wife physically pushing him out of the way, but her physical dominance only worsens his sense of impotence. After making his drastic and irreversible decision, Il-rae is left alone and reeling from the worst kind of failure and regret. From this point on he’s marooned in his very own limboland, hovering on the brink of life and death.

Beginning with POV shots of a car dutifully following the only path laid out for it, A Mere Life states its bleak indie intentions right away as the gloomy lyrics of a folk tune run in the background constantly making reference to a despair which not even death could comfort. Recalling the great misery epics of the ‘70s, Park Sang-hun films with an anxious, unblinking camera save for the ominous shaky cam shots of a man facing the sea which begin and end the film. Il-rae may have made a decision as regards a future, but it remains unclear if there is any hope of salvation waiting for him. A Mere Life is never is never an easy watch thanks to its unshaking bleakness, but its strength of purpose and uneasy mix of morality play and character drama make for an unusual, interesting independent feature debut.

Reviewed at the 2016 London Korean Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by

Review of Byun Young-joo’s Helpless (화차, Hwacha) first published by  The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

The recently prolific Sion Sono actually has a more sporadic film career dating back to the early 1980s though most would judge his real breakthrough to 2001’s Suicide Club. Back in the ‘90s Sono was most active as the leader of anarchic performance art troupe Tokyo Gagaga. Taking inspiration from the avant-garde theatre scene of the 1960s, Tokyo Gagaga took to the streets for flag waving protests and impressive, guerrilla stunts. Bad Film is the result of one of their projects – shot intermittently over a year using the then newly accessible Hi8 video rather the traditionally underground 8 or 16mm, Bad Film is near future set street story centring on gang warfare between the Chinese community and xenophobic Japanese petty gangsters with a side line in shifiting sexual politics.

Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul.

Yusuke Iseya is a rather unusual presence in the Japanese movie scene. After studying filmmaking in New York and finishing a Master’s in Fine Arts in Tokyo, he first worked as model before breaking into the acting world with several high profile roles for internationally renowned auteur Hirokazu Koreeda. Since then he’s gone on to work with many of Japan’s most prominent directors before making his own directorial debut with 2002’s Kakuto. Fish on Land (セイジ -陸の魚-, Seiji – Riku no Sakana), his second feature, is a more wistful effort which belongs to the cinema of memory as an older man looks back on a youthful summer which he claimed to have forgotten yet obviously left quite a deep mark on his still adolescent soul. In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.

In old yakuza lore, the “ninkyo” way, the outlaw stands as guardian to the people. Defend the weak, crush the strong. Of course, these are just words and in truth most yakuza’s aims are focussed in quite a different direction and no longer extend to protecting the peasantry from bandits or overbearing feudal lords (quite the reverse, in fact). However, some idealistic young men nevertheless end up joining the yakuza ranks in the mistaken belief that they’re somehow going to be able to help people, however wrongheaded and naive that might be.

As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives.

As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives. The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with. All these years later, it’s easy to forget just how revolutionary the wheezy, breezy youthfulness of the French New Wave was. Kuro proves that there’s life in this whimsical, summer seaside feeling yet as three misfits find themselves holing up at a disused small hotel to think about what they’ve done until they learn to grow up a little.

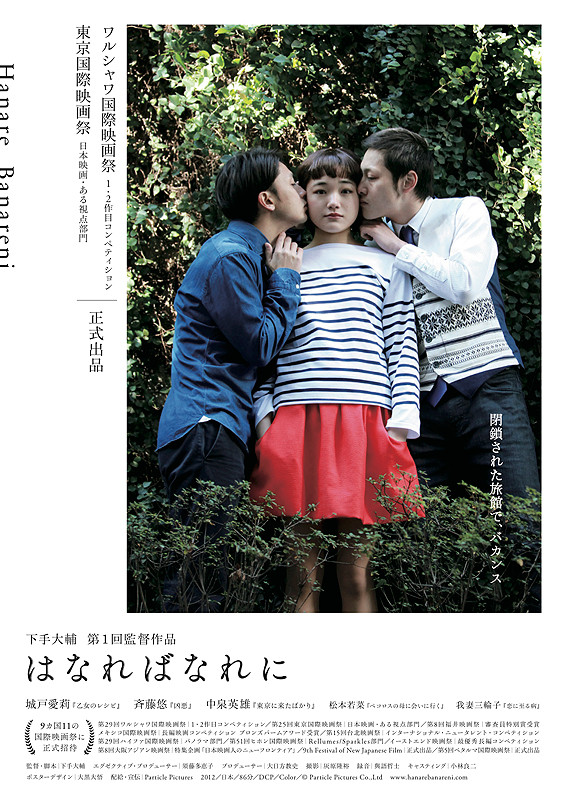

All these years later, it’s easy to forget just how revolutionary the wheezy, breezy youthfulness of the French New Wave was. Kuro proves that there’s life in this whimsical, summer seaside feeling yet as three misfits find themselves holing up at a disused small hotel to think about what they’ve done until they learn to grow up a little.