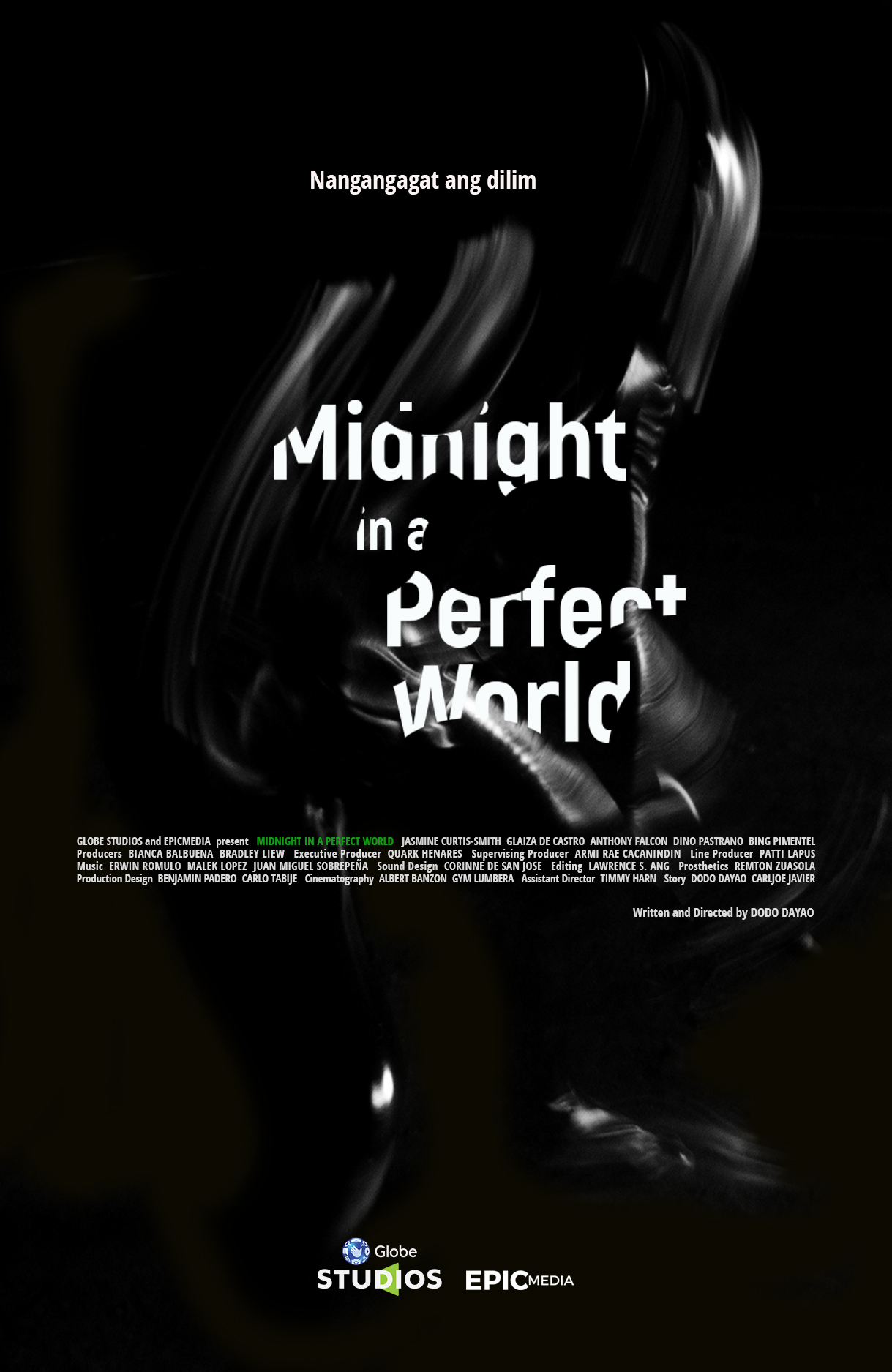

“It doesn’t matter what’s happening as long as nothing’s happening to me” a middle-aged woman exasperatedly exclaims, irritated by a young man’s naive curiosity. A dark exploration of the legacy of Martial Law, Dodo Dayao’s surrealist horror movie Midnight in a Perfect World asks how much of your freedom you’re prepared to sacrifice for security and if the illusion of a “perfect world” in which everything “just works” is worth the price of your complicity.

In a near future Manila in which all of the city’s infrastructural problems have been solved, conspiracy theorist Tonichi (Dino Pastrano) is convinced that a mysterious force is disappearing people in random parts of the city after midnight, a theory which is only strengthened after his friend Deana rings him in a panic convinced she’s become a victim of his “blackouts” and insisting that someone’s stolen the moon. Tonichi’s other friends, the sensible Mimi (Jasmine Curtis-Smith), reckless Jinka (Glaiza de Castro), and melancholy hospital worker Glenn (Anthony Falcon), are less convinced but caught in the street after midnight the gang have no option but to look for a “safe house” in order to escape the creeping darkness. For unexplained reasons, Tonichi is unable to enter with his friends and finds himself trapped outside in “God’s Blindspot”, as the mysterious Alma (Bing Pimentel), a middle-aged woman and safe house veteran, describes it.

Alma might in a sense be seen as the embodiment of the Martial Law generation, holing up in her safe house minding her own business and defyingly not caring what’s going on outside determined only to make it through the night. She offers cryptic words of advice to the youngsters, but does not really try to help them outside of trying to prevent them from interfering with her own survival. The so-called safe house has a hidden upper floor apparently invisible from the outside and hiding its own secrets. When one of the gang manages to break open the door and pays a heavy price for their curiosity, Alma merely creeps forward fearfully and closes it again ensuring she is safe from its myriad horrors even in her wilful ignorance.

Still, you have to ask yourself why if this world is now so “perfect” the youngsters seem so unhappy. Their drug use appears not to be particularly hedonistic but may offer them a degree of escape from a society which has become oppressive in its efficiency. Sensible Mimi cautions Jinka against associating with smarmy drug kingpin Kendrick (Charles Aaron Salazar) who spins bizarre stories of weird aliens while proffering a new drug which supposedly feels “like dying and going to heaven.” On her way from Kendrick’s Jinka passes a group of intense men and immediately pegs them as a hit squad, realising that Kendrick’s hideout has been exposed and she herself may now be in danger in an echo of the extra-judicial killings which have become a grim hallmark of Duterte’s Philippines. “Beta version Martial Law” is the way Jinka later describes it, drug users now taking the place of “activists” as targets not solely of legitimate authority but vigilante bounty hunters. The rumours of strange disappearances, people “erased” from their society, are yet another means of control inviting complicity with an unofficial curfew for a population ruled by fear.

As if to ram the allegory home, Dayao ends the credit roll with the Martial Law era slogan “Sa ikauunlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan” or “For the nation’s progress, discipline is needed” followed by the English phrase “Never Again”. Yet, it is happening again, the extra-judicial killings of the Duterte era no different from the disappearances of “activists” under Marcos. Jinka refers to the old Manila as the world capital of malfunction, its transformation seemingly brought about by a mysterious force but unlike Mimi who seems otherwise prepared to accept complicity in her “everything works” conspiracy theory remains dejected and suspicious. None of these young people is happy with their new utopia or prepared to pay the price demanded to live in it yet there appears to be no real way to resist and their eventual decision to brave the darkness exposes nothing so much as their naivety. Scored with eerie sci-fi synths and often shot in total darkness, Dayao’s surreal horror show offers a bleak prognosis for the contemporary society unable to escape from the permanently haunted house of an authoritarian legacy.

Midnight in a Perfect World screened as part of this year’s Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival (NIFFF).

Original trailer (English subtitles)