There had been films that dealt with the war before, but it was really with the generational shift that occurred among filmmakers in the mid-1960s that there was a greater willingness to reckon with the wartime past. Sadao Nakajima’s Classmates (あゝ同期の桜, Aa Doki no Sakura) was the first in a planned trilogy of war films at Toei, which was in other ways a studio that often leaned towards the right with its steady output of yakuza films, and most likely for that reason struggled to gain approval from studio heads. Taking its name from the military academy song, the film was inspired by a collection of essays put together from the letters and diaries kamikaze pilots had left behind. Nakajima had seen some of the letters sent back by the brother of a school friend, and reading them again on publication was determined to turn them into the film.

Nevertheless, only 25 years on from the end of the war it remained a sensitive topic. The film follows the men of the 14th class of reserve students who had previously had their draft notices deferred until they finished university but were now called up early because the war was going so badly. The majority of these men were allocated to kamikaze units and subsequently died in suicide attacks on US warships, though they received little in the way of training and mostly failed to hit their targets due to having limited fight experience.

What might seem most surprising is that several of the men voice their opposition to the war along with the realisation that Japan is going to lose. Early on in training, one man deserts but the others are reminded that to do so amounts to treason and once caught, deserters will be executed by firing squad. This turns out not quite to be the case. Shiratori (Hiroki Matsukata), the resigned hero, encounters Taki (Mitsuki Kanemitsu) in Okinawa. where he’s working as ground staff. He’s insensible and appears to have lost his mind. The man working with him suggests that he was tortured so badly that it’s left him in a vacant state, though he’s still deployed for mindless tasks because they just don’t have the manpower.

Part of the reason for that is that they keep ordering people to die in a validation of the death cult that is militarism. On their arrival, the instructor tells the men he will have them all die, because dying for the emperor is their duty and destiny. The top brass insist this is the only way to win the war even though it’s counterproductive in that they’re running out of aircraft and skilled pilots even if one officer callously remarks that they have an endless supply of bodies. There’s also no real reason to send the planes up with two pilots as opposed to one, but they leave fully manned. The suicide missions are supposedly “voluntary”, but the men can’t really refuse due to a combination of peer pressure and military order.

When one pilot, Nanjo (Isao Natsuyagi), returns to base having been unable to reach his target, he’s immediately set upon by the others as a coward and a traitor. They accuse him of being afraid to die, leaving him feeling ashamed and frustrated by a sense of injustice while admitting that he didn’t want to die like a dog. He knows that he would not be able to go on living afterwards if he simply didn’t go through with it because the stigma of being a coward who let other men die so he could live would always be upon him. Eventually, he becomes so determined to prove himself that he insists on getting right back in his plane once it’s repaired and then blows himself up on the runway to prove a point.

Nanjo’s case is all the more poignant because he was a new father whose son was born after he was called up. He appears to have married quickly against his parents’ wishes and is now anxious that his family won’t accept his wife and child who will be left alone when he dies. His wife (Yoshiko Sakuma) desperately tries to see him to show him the baby, but manages only a few seconds before he’s forced to return to the barracks. Given a little more time, she brings a wedding dress for the impromptu ceremony they presumably skipped before, but ends up tearing it and giving Nanjo a strip as a kind of good-luck charm though like everything else it’s a gesture filled with futility.

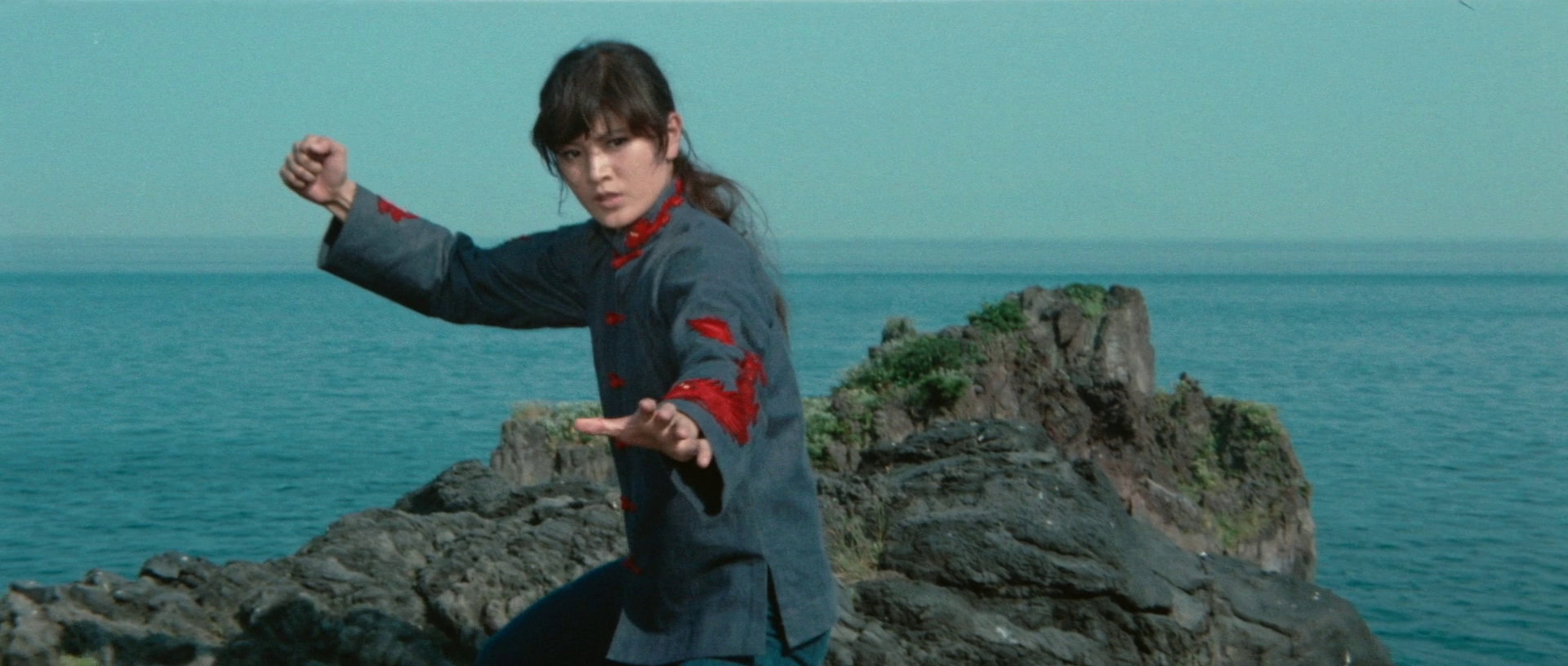

It’s this sense of futility and resignation that seems to overtake Shiratori who knows he cannot escape his fate. To desert to is be killed anyway or to experience a spiritual death like Taki. He had introduced a friend, Hanzawa (Shinichi Chiba), to his sister and the two had become close, but he is forced to abruptly break up with her because he knows it’s unfair to string her along when he’s been sentenced to death. Reiko (Sumiko Fuji) will lose her brother and her boyfriend on the same day. Hanzawa and the other men visit a brothel on the night before their mission where they are treated as “gods”, though he sees only irony in the situation in which they are more like human sacrifices offered in prayer for an impossible victory. Their deaths will have no real meaning and are really only intended to instil fear in the enemy and weaken their morale rather than cause actual material damage to their fighting capability. Making use of stock footage, Nakajima freeze frames a plane in flight and points out at that point the men inside were still alive before cutting to a title card confirming the war ended just four months later. The title card at the beginning dedicated the film to the souls of those who died in the Pacific War, though it’s perhaps as quietly angry as it was permitted to be in 1967 in the senseless sacrifice of these men’s lives who were shamed, tricked, or forced at gunpoint into their cockpits and told they were disposable while those who stayed on the ground cheered and whooped at the grim spectacle of death.