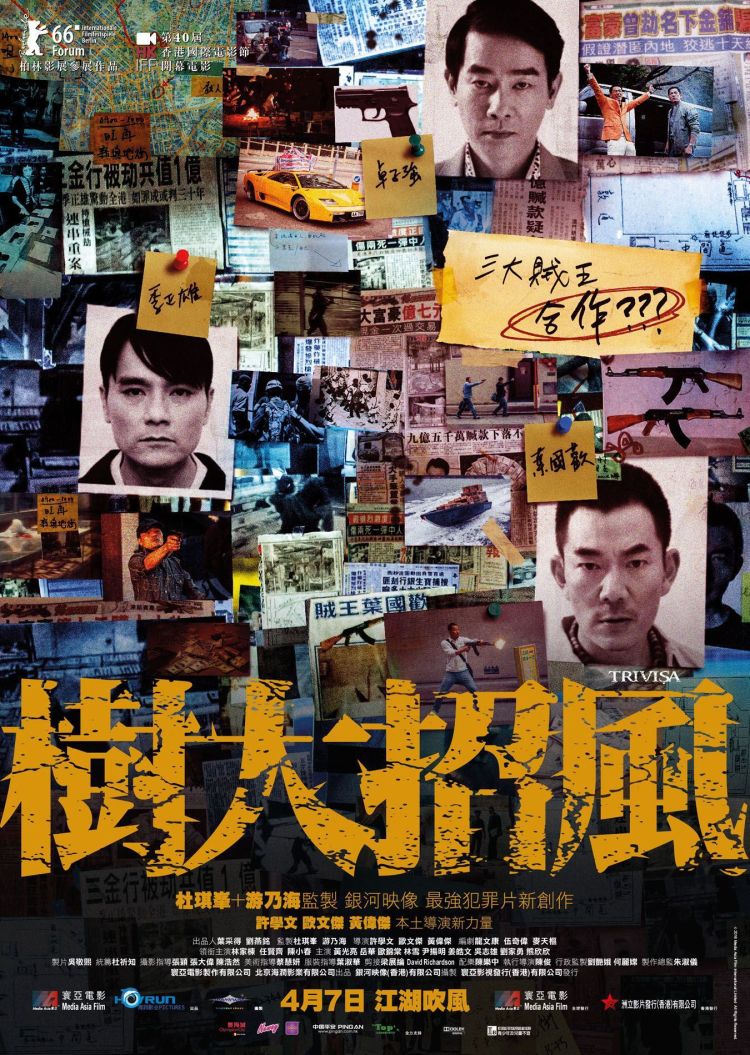

It’s worth just taking a moment to appreciate the fact that a film named for the three Buddhist poisons – delusion, desire, and fury, is intended as a criticism of Hong Kong as an SAR that revels in the glory and subsequent downfall of three famous criminals who discover that crime does not pay right on the eve of the handover. Mentored by Johnnie To, Trivisa (樹大招風) is directed by three young hopefuls discovered through his Fresh Wave program each of whom directs one of the film’s three story strands which revolve around a trio of famous Hong Kong criminals.

It’s worth just taking a moment to appreciate the fact that a film named for the three Buddhist poisons – delusion, desire, and fury, is intended as a criticism of Hong Kong as an SAR that revels in the glory and subsequent downfall of three famous criminals who discover that crime does not pay right on the eve of the handover. Mentored by Johnnie To, Trivisa (樹大招風) is directed by three young hopefuls discovered through his Fresh Wave program each of whom directs one of the film’s three story strands which revolve around a trio of famous Hong Kong criminals.

Back in the ‘80s, as Mrs. Thatcher delivers her pledges on the Hong Kong handover, King of Thieves Kwai Ching-hung (Gordon Lam) gets stopped by a random police patrol, kills the officers, and then has to fake his identity to escape. 15 years later he’s a petty mobile phone trafficker dreaming of pulling off a big score. Meanwhile, Yip Kwok Foon (Richie Jen), once known for his AK47 brandishing robberies is a “legitimate businessman” smuggling black market electronics into Hong Kong and bribing Mainland officials to do it, while Cheuk Tze Keung (Jordan Chan) is a flamboyant gangster revelling in underworld glory and dreaming of eternal fame.

Rather than weave the three stories into one coherent whole or run them as entirely separate episodes, the three strands run across and through each other only to briefly reunite in the ironic conclusion. The most famous of the three real life criminals, Kwai Ching-hung’s arc is perhaps the most familiar though rather than fighting an existential battle against his bad self, Kwai’s quest is to regain his title as Hong Kong’s most audacious thief. To do this, he’s reunited with an old friend and comrade in arms who’s retired from the life and married a Thai woman with whom he has an adorable little daughter. Unbeknownst to him, Kwai has not come for old times’ sake but is taking advantage of the fact that the family live directly opposite his latest score. Employing two Mainland mercenaries, Kwai has his eyes on the prize but his friend is wilier than he remembered, is quickly suspicious of Kwai’s friendship with his daughter, and has his suspicions confirmed when he finds his kid’s backpack full of guns.

Yip’s story, by contrast, is one of diminished expectations and ongoing financial woes. An early scene at a restaurant finds Yip in the company of Mainland officials to whom he must scrape and bow, placating them with various bribes and engaging in the strange trade of precious vases which seems to pass as currency among corrupt civil servants. Corporate shenanigans and business disputes, however, are no substitute for good old fashioned firefights and Yip’s frustration with his new career is sure to lead to some kind of explosion at some point in time.

Cheuk becomes the lynchpin of the three as he takes an advantage of a rumour that the three “Kings of Thieves” are getting together to plan a giant heist to track down the other two and see if he can make it work for real. The most successful and happiest in his life, Cheuk has made his fortune out of ostentatious crime – kidnapping the sons of the extremely wealthy for hearty ransoms. He is, however, bored and dreams of making a giant splash which will ensure his name remains in the history books for evermore – i.e., blowing up the Queen.

Facing the approaching handover, each is aware the world will change, unsure as to how they’re in the process of trying to secure their futures either way. Kwai wants one last heist, Yip has already begun courting Chinese business, and Cheuk just wants to be the face in all the papers across the entire Chinese world. Kwai’s sin is “desire” – he wants one last hit as a criminal mastermind and he’s willing to take advantage of his friend (and even his friend’s young daughter) to get it, Yip’s sin is “fury” as dealing with constant humiliation leaves him longing for his AK 47, and Cheuk’s failing is “delusion” in his all encompassing need to be the big dog around town, all flashy suits and toothy grins. On the eve of the handover they all meet a reckoning – betrayal, a stupid and pointless death, or merely ridiculous downfall.

The heyday of crime has, it seems, ended but that’s definitely a bad thing, laying bare a change in dynamics between nations and a decline in the kind of independence which allows the flourishing of a criminal enterprise. Bearing To’s hallmark in its tripartite structure, ironic comments on fate and connection, and eventual decent into random gun battle, Trivisa is a ramshackle exploration of a watershed moment in which even hardened criminals must learn to live in a brave new world or risk being consumed by it.

Screened at Creative Visions: Hong Kong Cinema 1997 – 2017

Original trailer (English subtitles)

The latest instalment in Wilson Yip’s SPL series stars Louis Koo as a Hong Kong cop on a mission to rescue his daughter from Thai kidnappers. Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance to present the film’s UK premiere.

The latest instalment in Wilson Yip’s SPL series stars Louis Koo as a Hong Kong cop on a mission to rescue his daughter from Thai kidnappers. Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance to present the film’s UK premiere. Ann Hui’s 1999 drama documents the struggle of a group of idealists fighting for the rights of boat people and their mainland wives.

Ann Hui’s 1999 drama documents the struggle of a group of idealists fighting for the rights of boat people and their mainland wives. Simon Yam and Lam Suet star in Johnnie To’s missing gun thriller.

Simon Yam and Lam Suet star in Johnnie To’s missing gun thriller. Eric Tsang plays the estranged father of a young man (Shawn Yue) recently released from psychiatric care in Wong Chun’s powerful debut. UK Premiere.

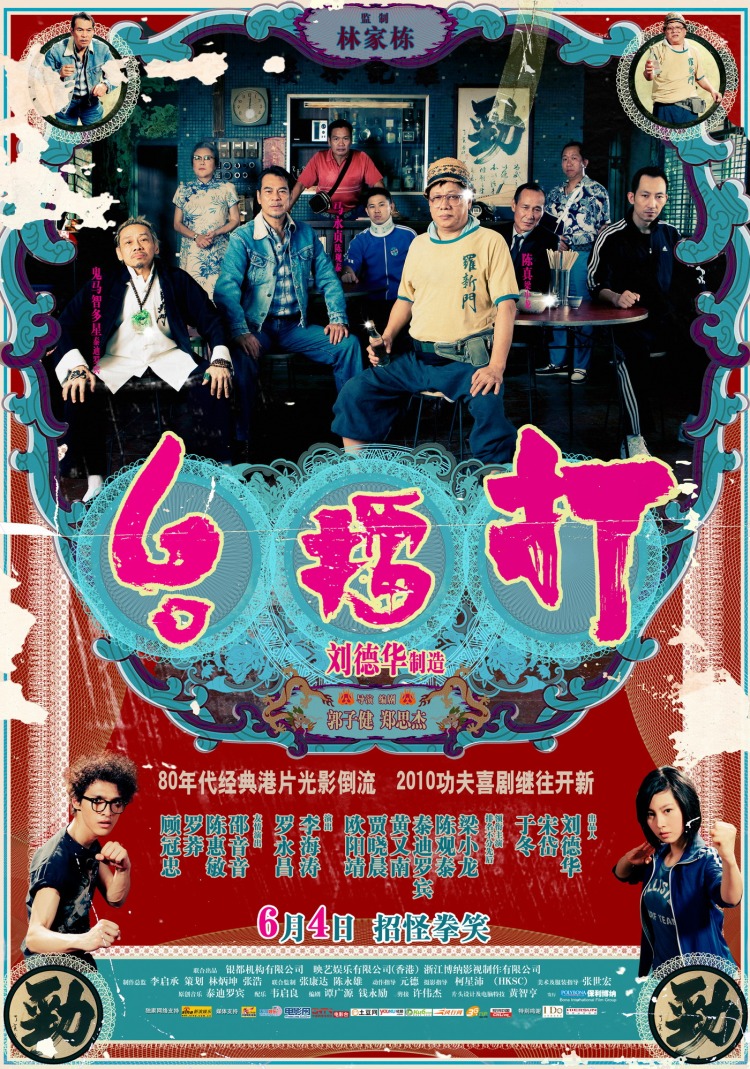

Eric Tsang plays the estranged father of a young man (Shawn Yue) recently released from psychiatric care in Wong Chun’s powerful debut. UK Premiere. A tribute to the kung-fu classics of the ’60s and ’70s, 2010’s Gallants follows two martial artists patiently waiting for their master to wake up from the coma he’s been in for the last 30 years. Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance.

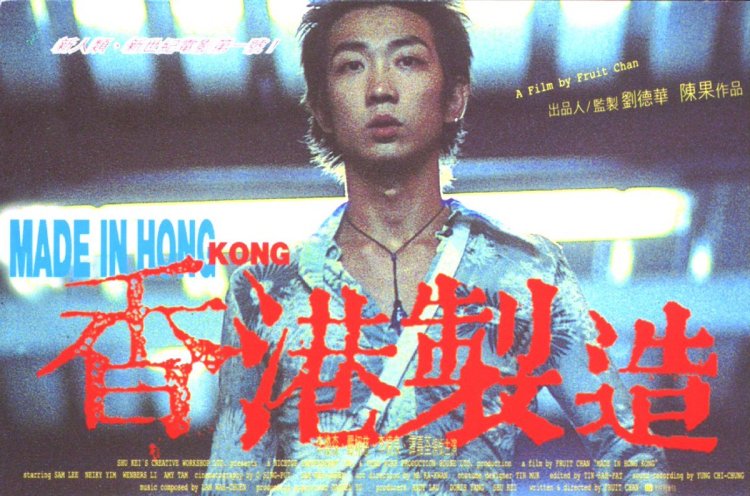

A tribute to the kung-fu classics of the ’60s and ’70s, 2010’s Gallants follows two martial artists patiently waiting for their master to wake up from the coma he’s been in for the last 30 years. Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance. Fruit Chan’s 1997 story of tragic youth in its 2017 restoration which premiered at the Udine Far East Film Festival.

Fruit Chan’s 1997 story of tragic youth in its 2017 restoration which premiered at the Udine Far East Film Festival. Director Alex Law paints an autobiographical tale of growing up in a working class family in late ’60s Hong Kong.

Director Alex Law paints an autobiographical tale of growing up in a working class family in late ’60s Hong Kong. Three infamous criminals smuggle themselves into Hong Kong for the biggest heist ever in a crime thriller produced by Johnnie To and directed by three proteges from his Fresh Wave short film programme.

Three infamous criminals smuggle themselves into Hong Kong for the biggest heist ever in a crime thriller produced by Johnnie To and directed by three proteges from his Fresh Wave short film programme. A grizzled cop chases a gold smuggling fisherman through storms literal and metaphorical in Jonathan Li’s feature debut. UK premiere – Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance.

A grizzled cop chases a gold smuggling fisherman through storms literal and metaphorical in Jonathan Li’s feature debut. UK premiere – Co-star Gordon Lam will be in attendance.