Marriage is not always simple, but when you aren’t actually married (and one of you is technically still married to someone else) the difficulties can be all the more pronounced. Often neglected in comparison with some of his contemporaries, Shiro Toyoda is best remembered for his often humorous literary adaptations. Marital Relations (夫婦善哉 Meoto Zenzai), based on a 1940 novel by Sakunosuke Oda and runner up to Naruse’s Floating Clouds in Kinema Junpo’s top ten for 1955, is a prime example of his style as it examines the unconventional relationship between a spoilt younger son of a wealthy family and a feisty geisha who nevertheless remains devoted to him despite his often insensitive treatment.

In the early 1930s, the oldest son of a wealthy family has scandalised his conservative father by continuing to consort with a local geisha. Irritated, Ryukichi (Hisaya Morishige) elopes with Choko (Chikage Awashima) assuming that he will eventually get his own way only to find his father is just as stubborn as he is. Ryukichi is already married though living apart from his wife who has a serious illness and has returned to her family with their only child, Mitsuko. Nevertheless, Choko and Ryukichi manage to live together as man and wife even without the official paperwork, installing themselves at her parents’ tempura shop. Though the couple are happy enough, Ryukichi is unused to living without his family money and Choko soon has to go back to work.

Even in early Showa things were changing. Ryukichi, spoilt and made useless by access to his family fortune and previously secure path to succession, pouts and whines about his arranged marriage and the wife he’s abandoned, emphatically demanding a free choice of mate even if she happens to have been a geisha. Choko, a working class daughter of shopkeepers, seems to have been sold to the geisha house to fund her parents’ store – in fact, Choko’s abrupt decision to leave the geisha house will also have financial consequences which Ryukichi claims he will take up with his father. Even if Choko were not a geisha, she would likely not have been accepted by the traditional upper middle class family and her constant battle is always for recognition as Ryukichi’s significant other (or perhaps primary carer). Geisha she was though, and will be again thanks to Ryukichi’s recklessness and mistaken assumption that he will regain his former status simply by being his father’s son.

Not having had the luxury of a wealthy upbringing, Choko is (financially, at least) a realist and prepared to work hard for what she wants. Heading back into the geisha world as a hostess and entertainer, Choko is the sole breadwinner of their technically illegitimate union though Ryukichi cannot entirely break with his former habits, casually burning Choko’s carefully balanced housekeeping accounts book, and eventually spending all her savings on a night of debauchery. Nevertheless, it’s Choko who eventually takes the initiative and goes into business with a friend opening a successful night spot which cleverly caters to her internationalist clientele with a “traditionally Japanese” theme. Like many of Toyoda’s women, Choko is a hardworking, practical lady determined to make a success of everything she does even if she’s had the misfortune to find herself shackled to the inconvenient man child that is Ryukichi.

Eventually it all gets too much and Choko takes a drastic decision after receiving a cruel and thoughtless slight from Ryukichi’s brother-in-law who has been adopted as the heir to the family. This shocking incident aside, the tone is largely one of comic knowingness as Ryukichi continues with his various schemes to wheedle his way back into his elite social circle while Choko spends her time working hard to create something new. Ryukichi is the worst of the old world – lazy, entitled, often selfish and thoughtless (if well meaning and resolutely devoted to Choko), whereas Choko is the best of the new – resilient, hardworking, honest and kind. Towards the end, having settled some of their differences, Choko and Ryukichi appear to have cemented their coupledom for good but are suddenly confronted with another ugly aspect of class legacy when a former servant (and sort of friend) of Ryukichi’s passes them in the street now obviously raised in status, and blanks them even as they call out to him.

Ryukichi’s sister comments at one point that her brother’s personality has been warped by his strict upbringing and the pressure to conform to social conventions has meant that he doesn’t quite know himself, though at heart he is good and kind. She may indeed have a point, honest in his love, at least, both for his daughter and for Choko, Ryukichi finds he lacks the moral compass which comes with needing to live in an interconnected society rather than the deference associated with being “the young master”. Subtle political commentary aside, Marital Relations is a wry, humorous look at an unconventional family life as its put upon heroine does her best to rescue her consistently disappointing (if often amusing) unofficial spouse.

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –  History marches on, and humanity keeps pace with it. Life on the periphery is no less important than at the centre, but those on the edges are often eclipsed when “great” men and women come along. So it is for the long suffering Tose (Chikage Awashima), the put upon heroine of Heinosuke Gosho’s jidaigeki The Fireflies (螢火, Hotarubi). An inn keeper in the turbulent period marking the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and with it centuries of self imposed isolation, Tose is just one of the ordinary people living through extraordinary times but unlike most her independent spirit sparks brightly even through her continuing strife.

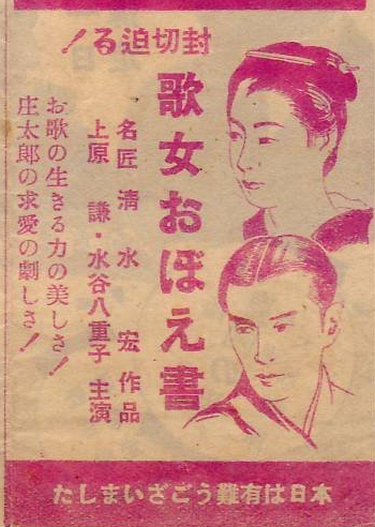

History marches on, and humanity keeps pace with it. Life on the periphery is no less important than at the centre, but those on the edges are often eclipsed when “great” men and women come along. So it is for the long suffering Tose (Chikage Awashima), the put upon heroine of Heinosuke Gosho’s jidaigeki The Fireflies (螢火, Hotarubi). An inn keeper in the turbulent period marking the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and with it centuries of self imposed isolation, Tose is just one of the ordinary people living through extraordinary times but unlike most her independent spirit sparks brightly even through her continuing strife. Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world.

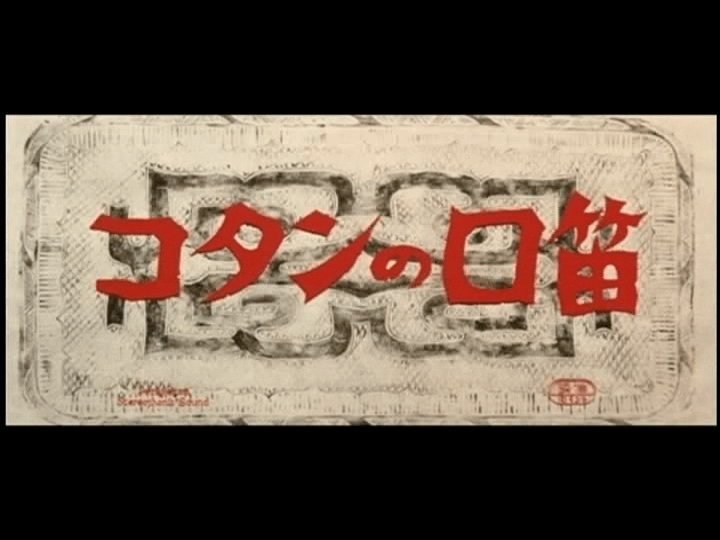

Filmed in 1941, Notes of an Itinerant Performer (歌女おぼえ書, Utajo Oboegaki ) is among the least politicised of Shimizu’s output though its odd, domestic violence fuelled, finally romantic resolution points to a hardening of his otherwise progressive social ideals. Neatly avoiding contemporary issues by setting his tale in 1901 at the mid-point of the Meiji era as Japanese society was caught in a transitionary phase, Shimizu similarly casts his heroine adrift as she decides to make a break with the hand fate dealt her and try her luck in a more “civilised” world. The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

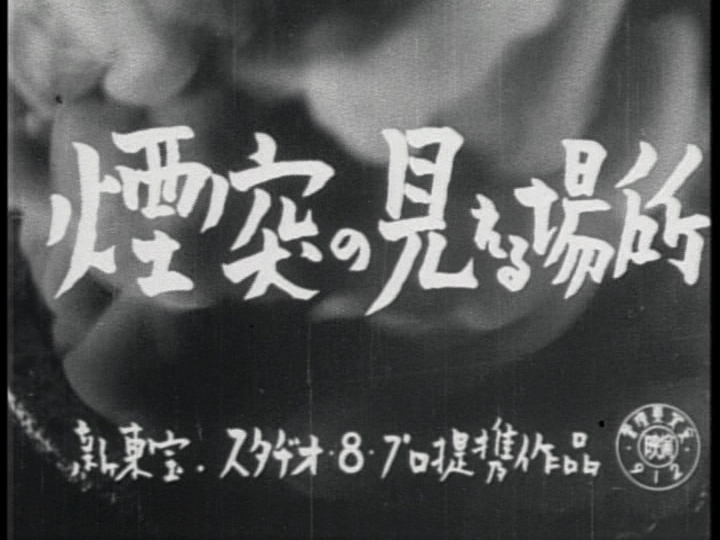

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.