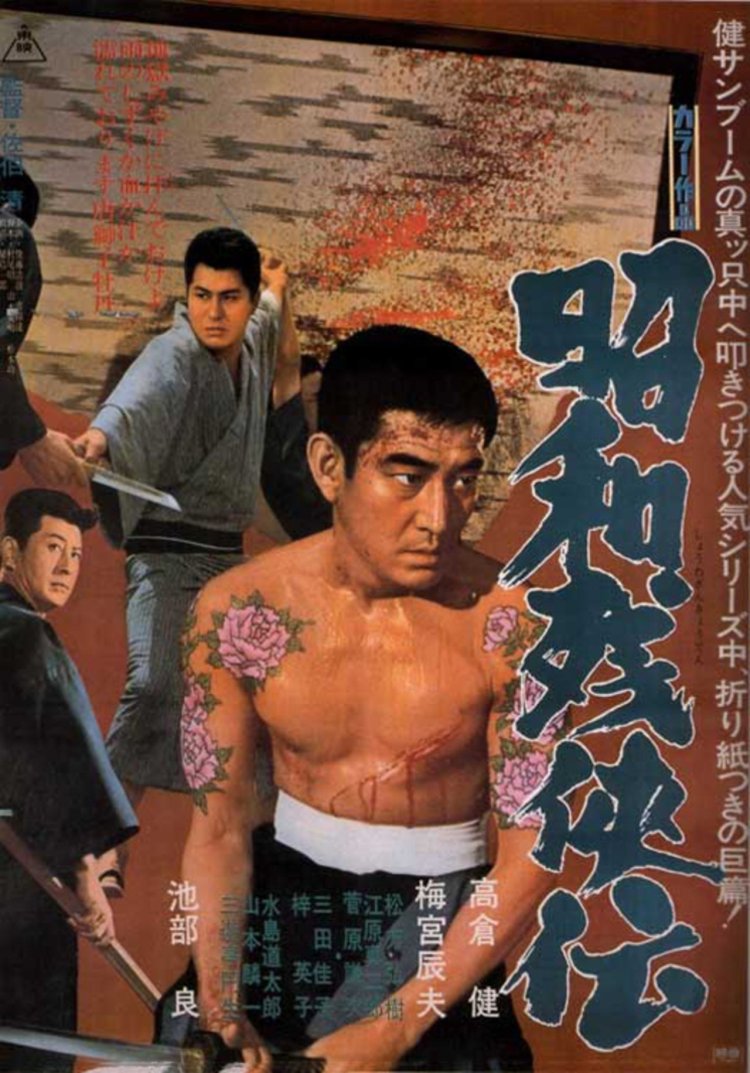

Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family?

Brutal Tales of Chivalry (昭和残侠伝, Showa Zankyo-den) – a title which neatly sums up the “ninkyo eiga”. These old school gangsters still feel their traditional responsibilities deeply, acting as the protectors of ordinary people, obeying all of their arcane rules and abiding by the law of honour (if not the laws of the state the authority of which they refuse to fully recognise). Yet in the desperation of the post-war world, the old ways are losing ground to unscrupulous upstarts, prepared to jettison their long-held honour in favour of a dog eat dog mentality. This is the central battleground of Kiyoshi Saeki’s 1965 film which looks back at the immediate post-war period from a distance of only 15 years to ask the question where now? The city is in ruins, the people are starving, women are being forced into prostitution, but what is going to be done about it – should the good people of Asakusa accept the rule of violent punks in return for the possibility of investment in infrastructure, or continue to struggle through slowly with the old-fashioned patronage of “good yakuza” like the Kozu Family?

Here is where we find ourselves in the 21st year of the Showa Era (1947) – the small marketplace in Asakusa is rife with black marketeers and illegal goods, but it’s still the only mechanism by which people are able to survive. The market is overseen by the elderly patriarch of the Kozu Family, Gennosuke (Tomosaburo Ii), who does his best to ensure a kind of “fairness” in its operation, at least in as far as yakuza rules extend. His territory is currently under threat from a rival gang – the Shinsei (literally “new truth”) who obey no such rules and are growing ever more ruthless in their quest to control the local area. Their big idea is to build an entirely new marketplace with a roof to make it a permanent and pleasant place for traders to do business – they will finance this through a kind of crowdfunding paid for by the merchants themselves who will also be paying protection money and kickbacks to the Shinsei. Everyone approves of the covered market project, even the Kozu, but if it means letting the Shinsei assume control is it a price worth paying?

This is a question which faces prodigal son Seiji (Ken Takakura) who returns from the war to find his city in ruins, Gennosuke murdered by the Shinsei, that he is now the new head of the Kozu, and that the woman he loved has been given away in a dynastic marriage to man from another minor clan. Before he died, Gennosuke was able to dictate two important instructions – that Seiji was to take over, and that the gang should proceed on a note of peace, avoiding violence or aggression where possible, leading by example rather than attempting to crush their new rivals. Seiji, having just returned from one battlefield is intent on following Gennosuke’s orders but how far can he really survive on the moral high ground when his opponents are content to fight dirty from down below?

The “Showa” era spanned some 60 years of turbulent Japanese history but in 1965 it was just under 40 years old and already beginning to generate the complicated feelings of nostalgia which are still attached to it today. Showa is right there in the Japanese title as if it were an age already passed but it’s clear in 1965 that something has shifted, one age has or is beginning to give way to another. The desperation of the post-war world with its empty, rubble strewn vistas and population filled with hunger and despair has ebbed away now that Japan is back on the world stage following the 1964 Olympics and the economy has as last begun to pick up. The young no longer fixate on the rights and wrongs of empire building, war and surrender but have begun to turn their attention towards the American occupation, social justice, and foreign conflicts. The young of 1947 were middle-aged in 1965, no one would begrudge them romanticising their youth, and so even if the world of Brutal Tales of Chivalry is a bleak one it still contains a kind of nostalgia for the kind of honourable gangster inhabited by Takakura who embodies traditional values some may feel are under represented in modern society.

Yet, for all that, there’s something subtly subversive in the film’s eventual suggestion that pacifism will only go so far and that one side or another must be banished from the battlefield through violence if peace is ever to prosper. Still, the struggle is a noble one in which honour is defined by strength of character and the selfless desire to ensure the well-being of others as much as it is to a blind observation of arcane rules and obsolete, meaningless ritual. The first in a long running series, Brutal Tales of Chivalry helped established Takakura’s iconic presence which eventually became synonymous with the “ninkyo eiga” as a personification of idealised Japanese masculinity, tough but caring even if passion is often repressed or redirected into violence. Remnants may be all that’s left of “chivalry” in the new Showa era, but there’s a degree of beauty in this brutality that refuses to die even as its era passes.

Now available on Region A blu-ray from Twilight Time (limited to 3000 copies only)

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

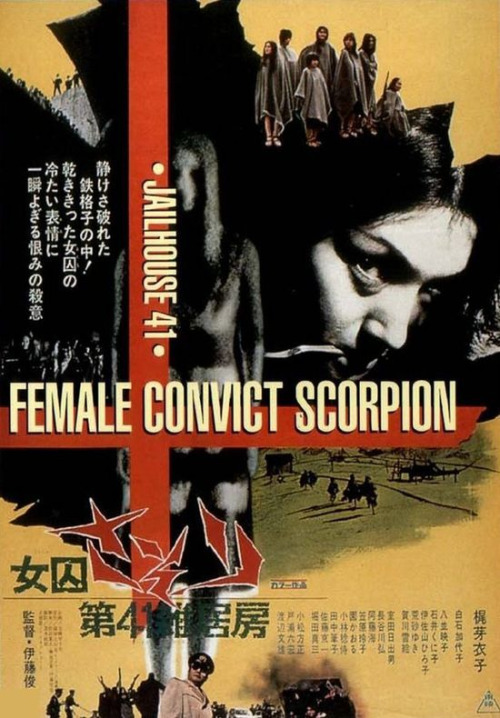

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of  Suffice to say, if someone innocently asks you about your hobbies and you exclaim in an excited manner “blackmail is my life!”, things might not be going well for you. Kinji Fukasaku is mostly closely associated with his hard hitting yakuza epics which aim for a more realistic look at the gangster life such as in the

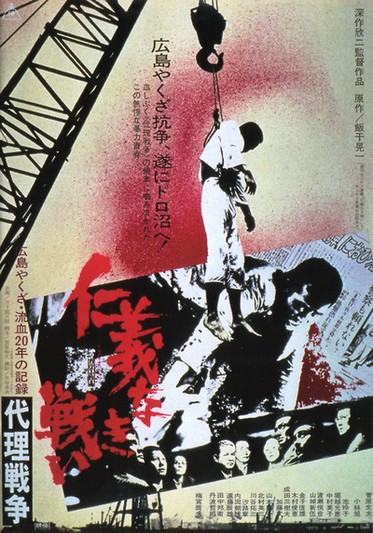

Suffice to say, if someone innocently asks you about your hobbies and you exclaim in an excited manner “blackmail is my life!”, things might not be going well for you. Kinji Fukasaku is mostly closely associated with his hard hitting yakuza epics which aim for a more realistic look at the gangster life such as in the  It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war.

It’s 1963 now and the chaos in the yakuza world is only increasing. However, with the Tokyo olympics only a year away and the economic conditions considerably improved the outlaw life is much less justifiable. The public are becoming increasingly intolerant of yakuza violence and the government is keen to clean up their image before the tourists arrive and so the police finally decide to do something about the organised crime problem. This is bad news for Hirono and his guys who are already still in the middle of their own yakuza style cold war. Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly.

Three films into The Yakuza Papers or Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Fukasaku slackens the place slightly and brings us a little more intrigue and behind the scenes machinations rather than the wholesale carnage of the first two films. In Proxy War we move on in terms of time period and region following Shozo Hirono into the ’60s where he’s still a petty yakuza, but his fortunes have improved slightly. If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of

If you thought the story was over when Hirono walked out on the funeral at the end of